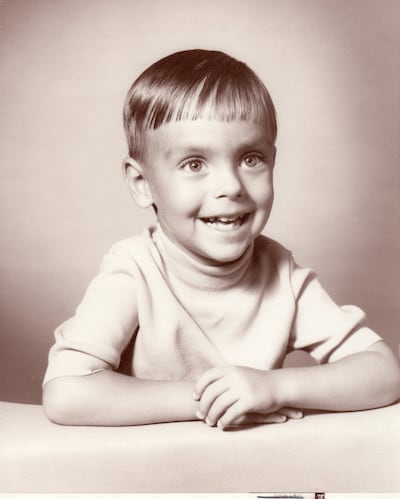

Even in his very first moments of life, Todd Curtis was beating the odds.

He was born in 1966 with spina bifida, a condition that would shape — but certainly not define — the rest of his life. When he was 4, his parents, Gary and Deanne Curtis, moved to the tiny Utah community of Copperton, and word traveled fast about the little boy in a body cast, extending from his left ankle all the way up to the middle of his chest and down to his right knee.

But even in his early formative years, Todd didn’t let it stop him from living his life. And that likely has a lot to do with how his parents raised him.

Deanne Curtis vividly remembers a 6-year-old Todd who decided it was time for the training wheels to come off his bike. She said he spent hours on the front yard sidewalk, determined to learn to ride on two wheels.

“He’d fall over, and he’d get up. And he’d fall over, and he’d get up,” Deanne Curtis recalled. “And he did this all afternoon.”

One of their neighbors, Uncle Ray, watched for hours from his front porch before he couldn’t stand it anymore. While Todd’s father kept watch over him, Deanne had gone inside because she, too, had had enough.

That’s when Uncle Ray called their home phone, and Deanne Curtis picked up. “He says, ‘Deanne, you’ve gotta bring that kid in,’” she recalled. “‘It’s killing us. We just can’t stand it.’”

“And I says, ‘Well, Uncle Ray, he’s going to do it until it gets dark, or he’s able to ride it, so I suggest you do what I did and just come in the house and just don’t watch him.’”

“So that was Todd.”

At the age of 56, after a hard-fought 18-month battle with cancer, Todd’s “grand adventure,” as he called it, came to a peaceful end on Saturday, March 18, surrounded by family. His death came about two decades too early, as he wrote in the opening line of his obituary.

Too early is right. But Todd also lived his life to the absolute fullest.

At 6, he eventually did learn to ride that bike. Later in life, he’d also learn how to drive stick shift, even though he had the option to learn on an automatic. To put his leg on the clutch, he’d have to manually move it with his hand.

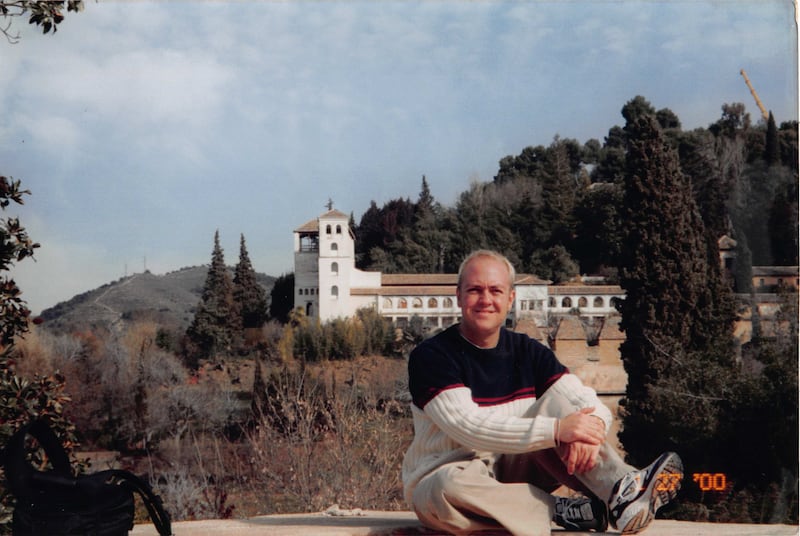

He’d go on to learn to scuba dive, ski and mow his own lawn (and his neighbors’, too, if he could beat them to it, which was often). Todd did it all. He also traveled all over the world to over a dozen different countries from Spain to Italy to Hong Kong. He even hiked the Cinque Terre, and he saw Pope John Paul II ordain cardinals, two memories he’d deem his favorite.

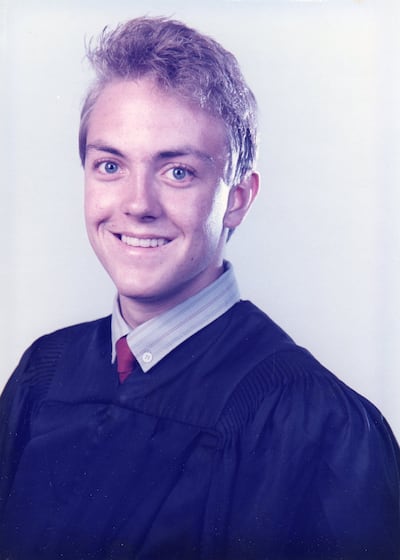

He’d also go on to work a long career with Utah’s oldest newspaper, the Deseret News, where he played a crucial and often thankless role in helping write Utah’s first draft of history for almost 36 years. He was hired first as a copy editor before going on to work as wire editor, assistant features editor and then eventually copy editor again as copy chief.

Last year, the Utah Headliners Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists awarded him with the coveted Lifetime Achievement Award, for which he was credited for “laboring quietly behind the scenes and laying the foundation for more than three decades of good journalism.” The role of copy editor doesn’t tend to come with the same notoriety as byline reporting, but it should. Todd’s co-workers often lauded him for saving them from making a fool of themselves through silly mistakes.

While Todd’s accomplishments were many, they do not fully tell the story of who he was. There’s a whole other piece of his life that may outshine — if that’s even possible — all of his achievements.

It’s how he treated people.

You couldn’t know Todd without also being his friend. Through simple acts of kindness and genuine interest in other people’s lives, Todd forged lasting friendships with not just his co-workers, but his neighbors, local brewers, his barber. Random people he’d meet in flower shops. And in his final days, his hospice nurse.

That’s why Todd’s departure from this world is especially heartbreaking for his hundreds — yes, hundreds — of friends.

Even though our time with Todd was cut far too short, he’s left us all with one last gift that will live on forever. One of his colleagues and close friends, Lois Collins, perhaps put it best: “A legacy of love.”

He paid the same attention to detail that he did in his copy editing duties as he did in every single one of his friendships, and in doing so he taught us it’s the little things in life — kind words and small gestures — that really matter. That’s why Todd touched so many lives around him.

“There just aren’t very many people who are (like Todd),” said Marilyn McKinnon, who worked with Todd on the copy desk when she was first hired in 1989 and stayed close friends with him.

“He wanted to know everything that had gone on in your life, and he really cared about what you were going through and what was happening in your life. And that’s really what makes him different, because most people are not that way. Most people are way more involved in their own lives.

“So I think that’s one thing we need to learn from him,” McKinnon said. “Pay attention to people in our lives. Try to understand them and care about what’s going on in their lives.”

‘A friend to all’

Andy Curtis, Todd’s younger brother by almost four years, has an excellent guess as to why Todd was the way he was — why he collected friends from so many different walks of life.

“I learned at a young age how I wasn’t going to treat people, because I saw how he was treated when he was young,” Andy Curtis said. Todd was “tough as nails,” he said, and didn’t want people to treat him any different because of his physical limitations. As Todd grew older and learned to control his quick wit and “big mouth,” he treated others simply how he wanted to be treated.

“He was different, so why would he not include you?” Andy Curtis said. “Why would he not be your friend if you’re different? ... Because he was different and all he wanted was to be liked and respected and loved.”

Todd’s youngest brother, Aaron Curtis, said it wouldn’t be uncommon for him to run into people that already knew Todd before realizing they were brothers, whether it was from work or school days decades prior.

“Todd was the type of person that made Salt Lake City very small,” Aaron Curtis said. “We could go through the state of Utah and play the six degrees of Todd Curtis.”

Wylie Gerrard, one of Todd’s closest friends, said there were “so many times” when he’d be with Todd, whether it be walking down the street or at a restaurant, “and he’d say, excuse me for a minute, I see somebody, I’ve got to go talk to them.’”

“He’d go talk for 10 minutes or so, and he’d come back, and he’d say, ‘Oh, that was so and so. I met him at a flower shop about a year ago, and I just wanted to go say hi,’” Gerrard said, laughing. “He would do that all the time. You couldn’t go anywhere with Todd without him running into half a dozen people that he knew.”

Brett Markum, who called Todd his closest friend in the past 15 years, said “there wasn’t anybody that didn’t like Todd. Really. He was everyone’s friend.”

Nannette Berensen, who met Todd when he competed on a speech team at the College of Eastern Utah in Price, said he “could make anyone feel instantly welcome and valued. If his neighbors needed anything, he would be out there doing their yard work, mowing their lawns, going to get them dinner.”

“He was just genuinely one of the most caring people, and was a friend to all,” she said. “For anybody that knew him, their life was enriched. They were a better person because of their association with him.”

Rae Purdy only knew Todd for the last month of his life as his hospice nurse, but she said he’s left a lasting impression. After a particularly hard day, Purdy said she broke down in tears when she saw the sadness in Deanne and Gary Curtis’ eyes.

She said Todd “just had this spirit about him, just pure light,” and she added he “put so many things for me in perspective.”

“He has touched my soul,” Purdy told Todd’s parents. “I’ll never be the same because of him.”

A tearful Deane and Gary Curtis said it was probably their old next door neighbor, Faye DeCol, who first put to words what Todd would bring into this world. They said she gave each of their children nicknames, and Todd’s nickname has more meaning now than ever.

“Todd’s nickname was ‘Sunshine,’” Gary Curtis said. “He brought so much sunshine into people’s lives.”

The neighborhood’s glue

When Todd was just 25, he moved into a little house in a Salt Lake City neighborhood just south of Liberty Park. For the next three decades, he’d earn a reputation not only as a meticulous caretaker of the property inside and out, but also a generous host that would throw the best patio parties.

But above all, his neighbors said he was probably the biggest reason the neighborhood would become so tightly knit.

In wake of Todd’s death, Markum, who moved into that Liberty Park neighborhood in 1997 and shortly after started his close friendship with him, said comments have been flying left and right that “the neighborhood won’t be the same without Todd.”

Markum said Todd knew everyone on the street, and he would constantly ask how everyone was. He’d also often plant himself in his front yard’s flower beds so he could say hi whenever someone would come by to check out a house for sale.

In 2014, Amy Ames and her soon-to-be-husband experienced that first-hand when they first looked at what would later become their home, right next door to Todd. She said they’d later decide to buy the house, in part because Todd made such an impression as the perfect neighbor. She said they also later found out Todd “had a hand” in helping them buy the home from his existing neighbor because he liked them too and he put in a good word.

“You could tell that he just had a deep love for this neighborhood, and a deep love for the people in it,” Ames said. “The way he talked about the people, the street, and the stories he shared. There was a legacy already there ... And that’s what we wanted.”

Ames said a new neighbor just recently moved in across the street from Todd after his death, and she said she felt “so sad they don’t get to know him.”

“Because he was the glue.”

Over the last few weeks, as Todd’s condition worsened, Ames said she was able to visit him several times, and she adopted a new motto “BLT: Be Like Todd.” She said during one of her final moments with him, she hugged him, and even though that night he was especially weak, she said when she told him she loved him, he opened his eyes and said, “I love you too.”

“I’ll never forget feeling so seen by him, literally hours before he passed on,” Ames said through tears. “I don’t know why we got that opportunity to be with him, but, man, we were so lucky and grateful.”

More than a copy editor

Todd formed deep friendships with many if not all of his co-workers, but perhaps one of the most impactful was with Scott Iwasaki, who started at the Deseret News soon after Todd. They were close in age, so that’s probably why they bonded so quickly, he said.

Iwasaki said he and Todd would spend time together in and outside of work. They’d attend parties together and often go out to the club Area 51 with friends.

“We were so close that when we did have disagreements, we fought like brothers,” Iwasaki said, laughing. “There were a couple of times in the newsroom we would stand up and just yell at each other. But the thing was, when we (would fight), it was for the same reason. We were trying to make something better for the newspaper.”

Whether it was disagreements about photos or conflicting deadlines, “there were times we would just get on each other’s nerves. But when it was all said and done we would finish up and then go and do something together.”

In 1998, Iwasaki said Todd helped him through his divorce.

“He was there. He was there just to make sure I was doing OK and I was being sane and not doing anything stupid,” Iwasaki said. “He had that soothing voice, you know, when he talked. And he really listened. ... No one listened to me like Todd.”

Iwasaki said he was “shocked” when he learned of Todd’s death, adding that he went to his Deseret News going away party in recent weeks that attracted literally hundreds of friends and current and former co-workers. That party, Iwasaki said, showed just “how many people he touched, how many people respected him, how many people loved him.”

“I lost a brother,” Iwasaki said through tears. “I wouldn’t be the same person if I hadn’t known Todd.”

Many of Todd’s co-workers, new and old, expressed how impressed they were with how meticulous he was as a copy editor — but also how he was able to maintain such professionalism throughout his career while also caring so deeply for his co-workers in personal ways.

While the news business has had its ups and downs, Todd constantly exuded positivity, even when things got tough.

Angelyn Hutchinson, who worked with Todd in the late 2000s when she was the features editor and he was her assistant, said he “kept plugging along with a very good attitude.”

Todd taught us all “life is what you make it,” Hutchinson said. “Even if bad things happen to you, how you react to it is up to you. He chose to be happy. He chose to live life to the fullest. He could have had a completely different attitude in life, but he chose to be happy.”

Saying goodbye

Asked how they have been coping with his loss, Todd’s brothers shared the same story.

Andy Curtis said he recently experienced two losses due to cancer. Two weeks before Todd died, he also lost his best friend to the disease. Andy Curtis said his friend fought to the end, and after his death, he could still feel him lingering in the room.

“I don’t know if it was him not wanting to leave or him wanting to console (his) family, I don’t know what it was, but you could feel it,” Andy Curtis said. But with Todd? “The moment I walked into the room when Todd was gone, I could feel he was gone. He wasn’t there to linger ... It was more like, buck up. Let’s go. I’m on to my next thing.”

Aaron Curtis said even though Todd handled life’s challenges with so much grace and dignity, now “he’s free.”

“Whoever came and got him, they were like, ‘Todd, we’re going to go have some fun. Let’s go,’” he said. “And I hope he’s running a marathon.”

alt=Katie McKellar

alt=Katie McKellar