Editor’s Note: The following story first appeared in The Maine Monitor’s free environmental newsletter, Climate Monitor, that is delivered to inboxes every Friday morning. Sign up for the free newsletter to get important environmental news by registering at this link.

From my apartment in Portland’s West End, I can see seagulls and squirrels, magnolia and maple trees, the occasional turtle dove that alights on the porch railing and enthralls the cats. The flower bulbs in my neighbor’s yard will begin to poke through the soil in the next several weeks, the buds will start appearing on the trees. Spring isn’t quite here yet, but it’s coming soon, inexorable.

This is phenology — the timing of seasonal change, and the ways it manifests in the behavior and cyclical transformation of plants, animals and ecosystems. This seasonal timing is changing, slowly but surely, as the climate warms — fall starting later, spring starting earlier. As we recently reported in this newsletter, winters in the Northeast have shrunk by three weeks in the past century.

Climate researchers need help from people on the ground to record real-time observations of this seasonal change, collecting enough of them with enough repetition to draw reasonable conclusions. Across the country and in Maine, more than 5,000 volunteers do this as part of the National Phenology Network, which is overseen by the University of Arizona with help from a number of federal science agencies.

When I was first learning to be a climate reporter, I would often ask people in my audience what they wanted to know about the crisis. The most common answer by far was, “what can I do that will matter the most?” There are lots of complicated ways to answer that question — but today I have a simple one: You can help scientists observe and track the effects of climate change, providing data that shows this change is here and happening, informs better predictions, and helps us to adapt our food system, infrastructure and more.

“[Researchers] could just never approach anything close to the volume that you can get if people from communities all over the state are out there in their backyards and in public parks and other places observing these changes,” said Beth Bisson, who helps lead Maine Sea Grant and the University of Maine’s phenology program, Signs of the Seasons.

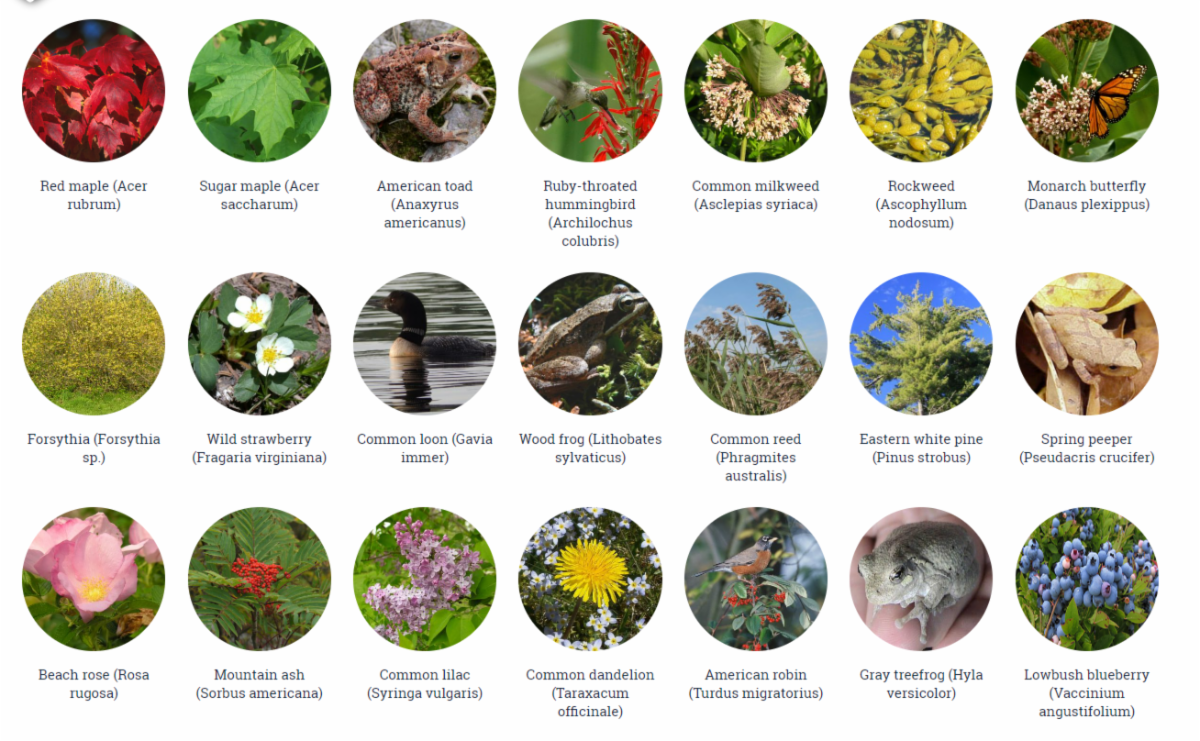

The program has a suite of “indicator species” with standardized protocols for volunteers to follow in making their observations, using worksheets and apps to count leaves, track dates and spot species. Maine’s program also has a protocol for observing rockweed on the coast. Participants are encouraged to go out once every week or two to observe specific seasonal changes happening around them.

“We have volunteers who do everything from selecting a single dandelion plant in their yard,” Bisson said, “to observing, you know, more than a dozen species on several different sites.”

Scientists can take a set of hundreds of volunteer observations of, say, the buds beginning to break on a red maple tree (pictured at the top) in a certain climatic zone or at a certain elevation. They can average these observations, and compare those averages from place to place and year to year, to gauge movement in the timing of a red maple’s seasonal transformation.

Paired with the factors like temperature and snow cover, this data can help turn hypotheses about climate change into empirically supported conclusions.

“We’re really trying to get at the complexity of that signal, and how plants are changing across the landscape,” Bisson said. “For example, if you’ve looked at a mountain in the spring, you can see that the leaf-out occurs at the lower elevations earlier than the upper elevations. And so if we can get a large number of volunteers, hundreds of individuals making observations all across the state, we have a much better understanding of how the changes are occurring, and how those changes may affect things like our sugar maple industry.”

The data can show “mismatches” emerging between interdependent plants and animals as these seasons move around. To this end, Bisson said, one focus of the Maine phenology program is on lowbush blueberries and their pollinators.

To explore the resulting data across the country, try this map tracking the early arrival of spring across the U.S. this year relative to the 1991-2020 average. It’s based on volunteer observations of lilacs and honeysuckle, now considered an official climate indicator in the federal government’s periodic National Climate Assessment. Or see how many different kinds of observations the network has generated over the years.

The program has informed more than 200 peer-reviewed papers over the years. There’s a study on the changing migrations of the beautiful black-and-white warbler, which breeds in part in the boreal forests of Northern Maine and Canada. Another study compared climate observations along trails in Acadia National Park against other parts of New England.

One recent study shows how the volunteer data can be used to model airborne pollen. This could mean better predictions for allergy season and how it’s changing in a warming climate. This was dismayingly summed up in a recent report by the nonprofit Climate Central as “earlier, longer and worse.”

It can be overwhelming to face the reality of these changes, knowing how they will worsen especially if greenhouse emissions don’t decline and to some extent even if they do. But Bisson said her work still feels mostly hopeful and positive.

In surveys, she said the majority of Maine’s phenology volunteers report that participating makes them more aware of climate impacts and “more likely to engage with stewardship actions related to climate change.”

“You’re generating useful data, but you’re also generating more of a connection yourself to the changes in the environment around you,” she said. “I find that I pay closer attention — it’s nice to slow down.”

Sign up for Signs of the Seasons trainings to become an observer — they’re currently scheduled in the next few weeks in Wells, Falmouth, Camden and Boothbay, with more pending. And let us know what you see out there.

To read the full edition of this newsletter, see Climate Monitor: Citizen data on shifting seasons helps climate scientists.

Reach Annie Ropeik with story ideas at: aropeik@gmail.com.