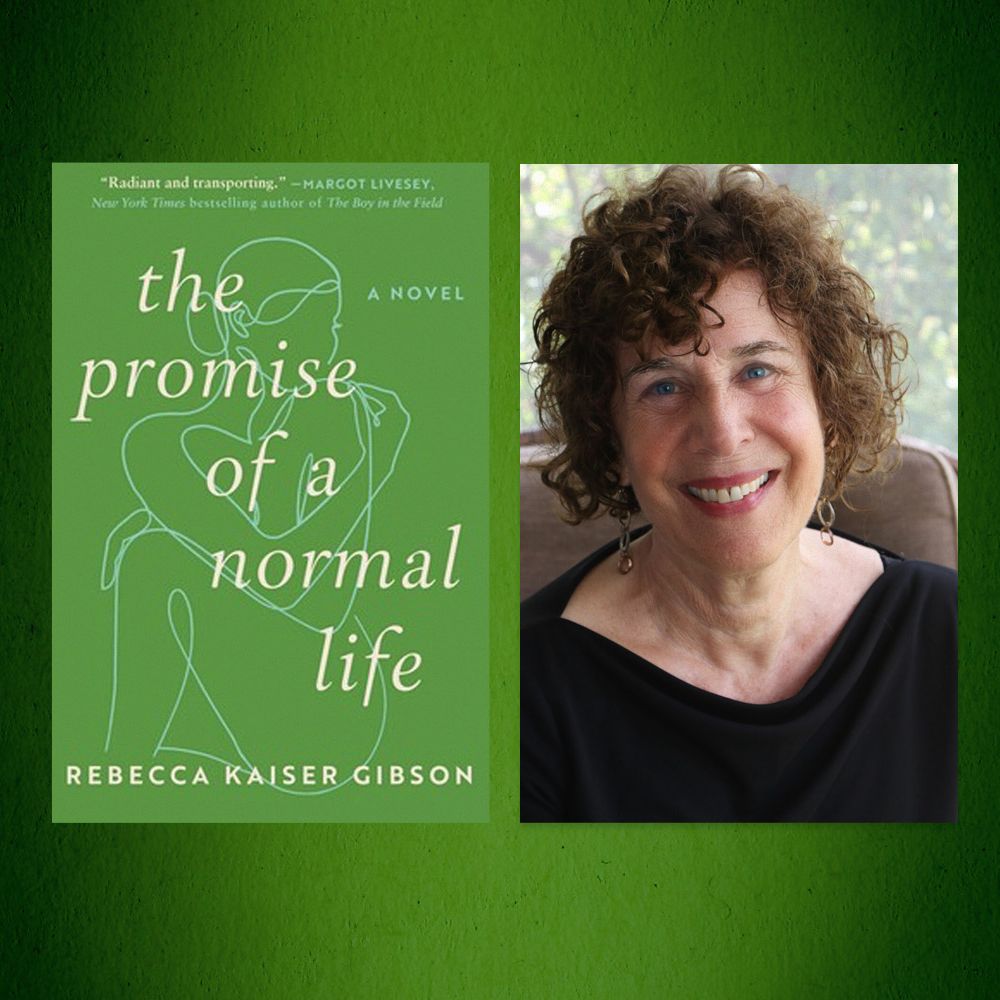

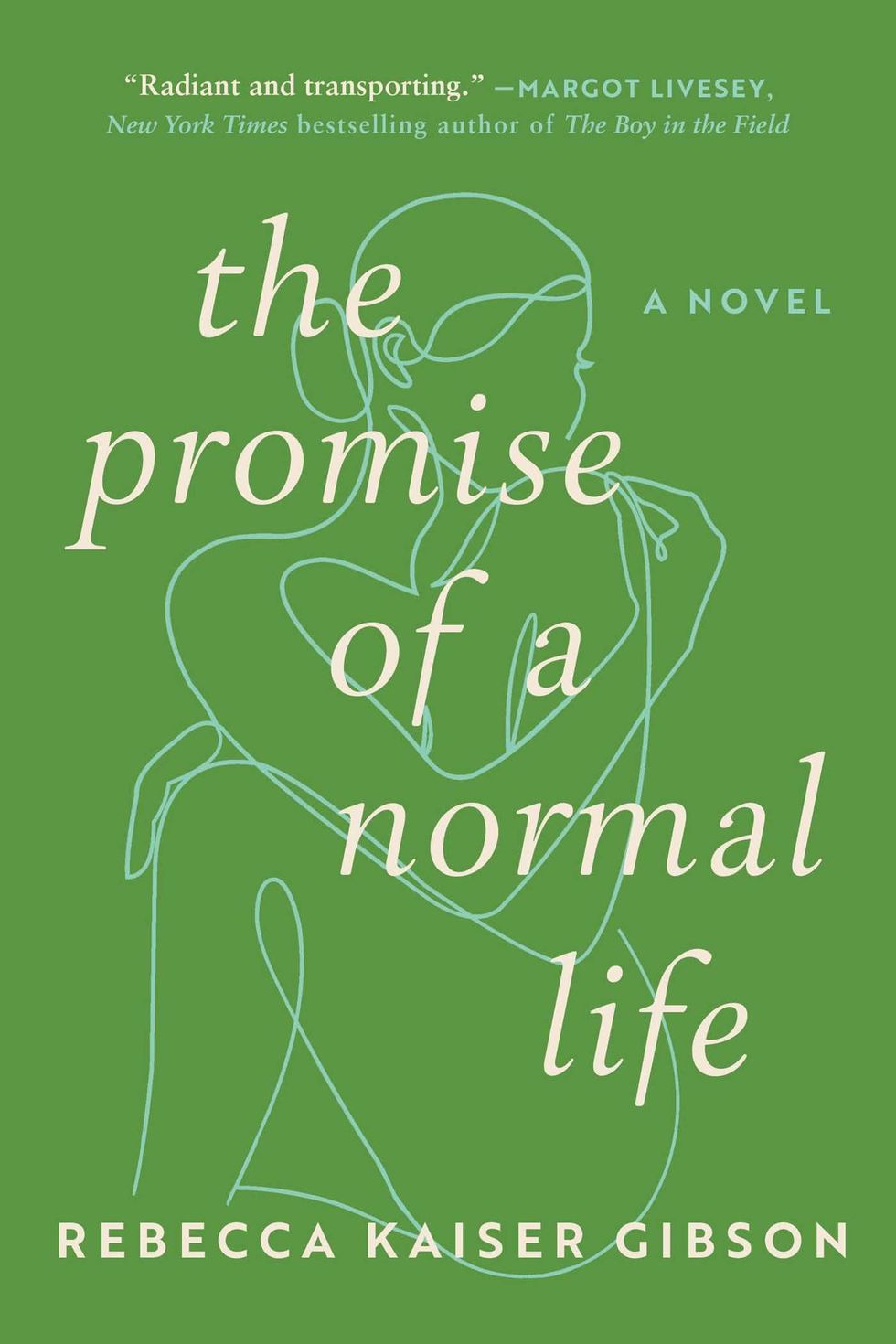

Like many of us, poet and educator Rebecca Kaiser Gibson spent some of the early days of the pandemic going through her closets. Unlike most of us, Gibson found piles of writing from the past several decades stacked in a corner of her office. With just a little reworking, The Promise of a Normal Life, Gibson’s first venture into the world of fiction, would be the result of the scenes she found.

The novel’s narrator, a dreamy girl who’s mostly along for the ride of her own life, is never named, though we are deep within her head. Our main character has a relatively peaceful childhood in the 1950s, with a kind father and driven doctor mother who are both heavily involved in the local Jewish community. As she navigates the world changing before her during the 1960s, her life gets more complicated as she grows up with deeply painful episodes like a sexual assault and a stunted marriage.

Shondaland spoke with Gibson about the experience of writing poetry versus fiction, building a passively observant narrator as opposed to a strong female character, and what it means to be “the silent one” in the Jewish faith.

SHELBI POLK: So, my favorite question to start with is where did this story come from? As broad or as granular as that may be.

REBECCA KAISER GIBSON: Where did it come from? Well, you know, it’s really weird. That’s a kind of spatial question, but it came from time. I wrote sections of the story for years. I sort of forgot I’d done them a long time ago in the ’80s. I did have a version of this, which I sent to an agent, who will remain nameless, for obvious reasons in a second, because he lost it. And a year and a half later, I got a call that said, “I’m really sorry. I lost this, but my intern found it. And here’s what I think.” He had all these comments. At that point, the main character was named Helen, and the structure of it was completely different. The story came from various sections that I just wrote, not thinking I was ever going to put them together. And during the pandemic, it was the year after I stopped teaching, and I thought, okay, it’s really quiet. I can’t go anywhere, and that’s when I found them all. I showed them to a friend of mine, and she said, “I think this is a book.”

By that point, I’d written these two poetry books. And I’ve done a lot of work on organizing the shape of the book. I thought I could put dates in, and then I could move things around. So hopefully, a chapter that comes after a thing that happened hopefully illuminates Oh, why did she do that? Oh, maybe she did it because of that. In retrospect, it looks like I was intrigued by how the mind works, and how it leads to a particular kind of mind that goes from a notion to associations and then back to the notion. So, I kind of like playing with a reader and hoping the reader would follow each part and then feel like, “Oh, we’re here now.”

SP: It’s funny — one of the things I actually had written down was that it feels kind of episodic, which makes sense since it was pieced together from all these years. So, I suppose you were thinking of it in vignettes?

RKG: Yes, absolutely. But it’s interesting. I think the way the character thinks is in episodes, not in linear, chronological order, and that’s part of her difference from her family. They think, “This leads to that, things are kind of orderly, and this is how it happens,” which I think is pretty familiar for people, actually.

SP: Did you have this character in mind as you were writing over the years, or did you build the character and then fall in love?

RKG: Yeah. So, I guess I did. Again, I wasn’t planning it, but that is the way I write anyway. I don’t sit down to write poems. I do little — like I’m trying to give myself a little present for later on. It’s a present from someone I don’t know, and I think, “Oh, okay, I can do something with that.” But I don’t have to take responsibility for it because someone else did it. It’s a weird trick that I do for myself, and I seem to enjoy it.

SP: That is so interesting because one of the things that was fascinating about this character to me was that it’s not that she doesn’t want anything, but she’s very confused about what she wants and how to want something that is not just handed to her. I don’t want to call her passive, but tell me about making a character like that. You pulled it off, but I feel like that’s a really dangerous choice to make.

RKG: Well, that’s really interesting because when I started writing it, I showed it to a woman who was much younger than I was, and she said, “Why is she so passive?” And I stopped writing those little things for several years because I felt so embarrassed. Like you’re not supposed to be passive. Remember the timing of the [Brett] Kavanaugh [hearing]? She gave me permission to write this book. Because I felt like if someone this coherent and upright and functional and smart did not choose to tell what happened to her at the time, why not? And then I thought, “That’s true of this character too.” It didn’t even dawn on her. Her father says, “Don’t,” so she doesn’t. And that “whole silence for reasons other than not telling the truth” was the premise of people who objected to her. All the forces make this character know that it’s not safe to even begin to say what you think because someone else is gonna come along and wipe it out with another version of reality, which isn’t hers. So, she just goes internal as a kind of survival mechanism. And it’s not just about the sexual assault scene, but it’s about everything. She doesn’t say what she’s thinking. She says what she’s thinking to us but not to anyone else. Nobody modulates her experience because she has decided or figured out, whichever it is, that it’s not safe to say what you actually are thinking because it doesn’t fit, and there’s no explanation for it. It’s the Me Too person who doesn’t say, “Me too.”

SP: It’s so hard to write characters who aren’t driven by some big, strong internal desire, but she’s very real. And I think she’ll resonate with a lot of women.

I was so struck by the juxtaposition of her with her mom, who is ambitious, strong-willed, and knows exactly what she wants. Tell me more about that relationship and building that contrast there.

RKG: I think her whole being is a result of that contrast. Her mother is the kind of person who fills the space with her reality and the pieces of her reality. She never tells the complete story to her daughter. She just gives these little punches of truth. I was thinking, “Okay, what would be the choices of a daughter of that kind of mother?” And one of them might be to fight back at the risk, maybe, of being squished. But that might make someone stronger and more able to come up with the language, like a debate or something. But she doesn’t make that choice. I think that choice is a real, motivating thing that will lead to a whole different life. I wonder if I’d written her with a different kind of mother, would she be like that? And I can’t even imagine. Would she have thrived in a kind of warm, gentle, permissive world? Who knows?

SP: What was it like moving from poetry to fiction?

RKG: I don’t know if I’ve moved from poetry to fiction, but my husband has always wanted me to write fiction. I’d read him things, and he’d say, “Why don’t you write that?” I don’t even know what I said to him. It’s really fun, actually, is what it is. It’s easier; don’t tell anyone. Because the sentences, they just keep going. They aren’t condensed in the same way, and it just feels different. It feels like a reverie kind of thing, whereas the poetry feels more like I’m entering space. Things are three-dimensional, and things are talking to each other in ways. I had fun writing the title chapters because it felt like that’s what I do with poetry.

The writing of course is really different, but the beginning to put the book out is completely different. When I do poetry readings, so far, I feel like the people who come are people who know me. With a novel, I feel like I may not know those people. Which would be great! You know, it’s a real risky thing because most people don’t pick up a poetry book if they don’t have some kind of way of connecting with it already. Whereas I think they do pick up [other genres of] books. It’s a whole different world.

SP: I was really drawn to our narrator’s observer perspective. She was very careful to watch in a way that almost made her feel like an outsider, even with her own family. I know intention is a tricky place to get to, but was that distance intentional?

RKG: That’s an observation that I hadn’t noticed, and of course, it is true. I hadn’t noticed her observing distances since I was focusing on the fact that the [act of] observing is what is important to her. I think it feels so much more personal and fresh to her. The rehearsed answers that she’s heard about everything on almost every topic — “Now my mother is going to say this, you know. Now the story about the way they met is going to be like this” — but that bores her. She doesn’t engage with it at all. There’s nothing there, so what’s there is all the stuff, all the dimension that’s around the family that she can access, which of course is limited because she has no context for anything. So, she makes all sorts of bad decisions, we would say on the outside. But it’s because she’s just observing and mirroring back what she sees, and it’s unmitigated by other people’s wisdom, even if there were any.

SP: Maybe it’s both? Perhaps it is the best way she can connect, and also the perspective keeps her a little bit apart.

RKG: Which, maybe, that’s part of the survival, actually, to be a little bit apart from what feels closed in: the repeated, ritual conversations. Personally, I also feel like that. I’m terrible at small talk. I can’t stand it.

SP: I was also really interested in her relationship with her religion. She takes comfort in it sometimes. Other times, she doesn’t think about it. It’s a great balance, compared to the more absolutist tradition I was brought up in.

RKG: [Traditionally,] there are four boys usually in the seder service, and I saw in a modern version of the four boys the silent one. I thought, “That’s better than the one who doesn’t know to ask.” It comes to the same thing. They’re silent. But why are they silent? Are they silent because they’re too spaced out to even figure it out, which is often the way it’s interpreted? Or are they silent because they understand something beyond the words? It’s not just the retelling, the “Here’s what happened when …” She would never say this, but it has to do with lots of words of connection, actually. She wants that kind of deep thinking and deep understanding of things. So, it doesn’t feel to me like it has to do with either ritual, or ordinariness, or preoccupation. You’re right — her connection is very intermittent. It doesn’t come up all the time in the book. It just sort of rides a little, and opens up sometimes, and then disappears.

Shelbi Polk is a Durham, North Carolina, based writer who just might read too much. Find her online at @shelbipolk on Twitter.

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY