Chloë Sevigny is wearing a rugby shirt to a playground somewhere in downtown New York. I know this, because she tells me. She quite literally says to me over the phone, “I’m wearing a rugby shirt right now by Rowing Blazers. It’s warm and it’s easy and it’s casual. It’s basically a nicer version of a sweatshirt,” before she pauses and adds, “I mean, it has a collar!”

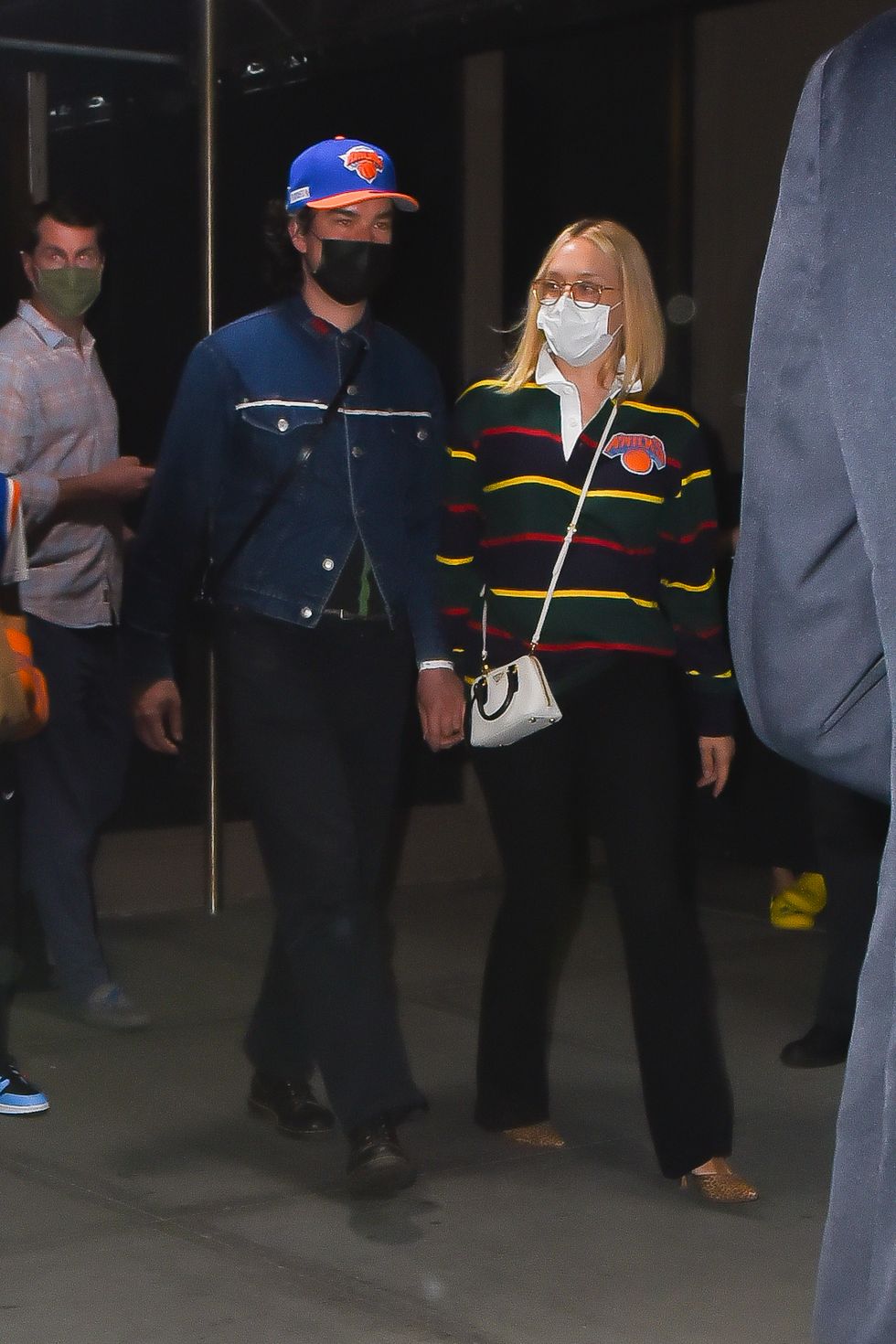

A couple months before, Sevigny had worn another rugby shirt to the first Knicks game of the season, but she considers that outfit a “misfire.” Originally, she wanted to style the shirt with black vinyl Margiela trousers, but it was an unseasonably warm fall day in New York, so she reached for a pair of black lace pants instead. These pants are what bother her about the look, but they also don’t really matter; the rugby shirt was the whole point.

It was actually two vintage rugby shirts, sliced and diced together, with thick horizontal stripes and thin vertical stripes converging at her hip. On the chest, the letters “PMS” were embroidered in pink cursive, and on the back, it had a logo with a woman in red stilettos riding a hot pink horse with a mane in the shape of “PMS,” encircled with the phrase “Strong women, better planet” in a pink-blue gradient. There was a lot going on, but Sevigny can make tiger-print stockings look like a neutral, so on her, the rugby still seemed downright unfussy.

On Delancey Street the day prior, a line of young downtown New Yorkers—people who I would bet money have at one point or another called Sevigny “mother”—waited outside a vintage shop in hopes of buying one just like it. The store, Big Ash, was selling 39 of the cut-and-sewn rugby shirts, designed by Sevigny’s close friend and stylist Haley Wollens, designer Raffaella Hanley of Lou Dallas, and graffiti artist and designer Claw Money (Claudia Gold). They sold out instantly and Ashley Louise Williams, who owns the shop, tells me that even two months later, “people have been coming by often, asking if we have any more left.” Williams has been on the hunt for vintage ones since; when she does find them, they’re gone as soon as they hit the racks.

So at present, a not-insignificant percentage of lower Manhattan is walking around wearing rugby shirts, designing rugby shirts, or desperately in the market for some rugby shirts. And there’s something really funny about this subset of New Yorkers, who’d rather save up for clothing grails than a house and who frequent archival vintage shops more than grocery stores, wearing the same thing as a mall-going teen somewhere in Georgia who couldn’t care less about the runway. Williams, who is from the South, tells me she thought the remixed rugbies were hysterical: “I loved that these edgy girls from New York decided to completely turn the tables on such a classic staple.”

But what exactly is it about this yuppie essential that makes it so desirable among people who want to look—and, in Sevigny’s case, are the embodiment of—cool?

Maybe it’s the fact that rugby, unlike tennis or polo or golf, comes with a bit of an edge. The sport never really caught on in America, but even if it had, it might not have gone over well with elitist types who didn’t want to roll around in the mud. Articles of Interest podcaster Avery Trufelman recently released a seven-part series, “American Ivy,” that dissects prep style. When I ask her about the appeal of the rugby shirt, she says, “I think it’s hinting at something that’s less aristocratic … it’s a little bit more down and dirty.”

Tony Collins, a British sports historian who specializes in rugby, tells me, “When rugby was first played at Rugby School in the English Midlands during the early 1800s, the boys (it was a boys-only school) wore ordinary shirts with collars and cuffs.” Eventually, the clothes evolved to be more durable. “The physical nature of the sport meant that shirts were often torn and were not warm enough for the English winter. So a heavier, more hard-wearing woolen shirt was introduced, and by the 1860s, this had become the accepted uniform for playing rugby.”

By the time Lisa Birnbach was publishing The Official Preppy Handbook in 1980, the rules of American prep culture had solidified and shifted into yuppie style, but the rugby shirt maintained a bit of rough-and-tumble attitude. People often think the original prep style was about looking rich, but that’s not quite true. It was about wearing the same thing you wore to sports practice out to class, and then to dinner and still appearing put together. (Granted, you’re also supposed to be rich while doing these things—but that’s the subtext, not the text.) It was about looking good without really trying, even if your shirt was muddy.

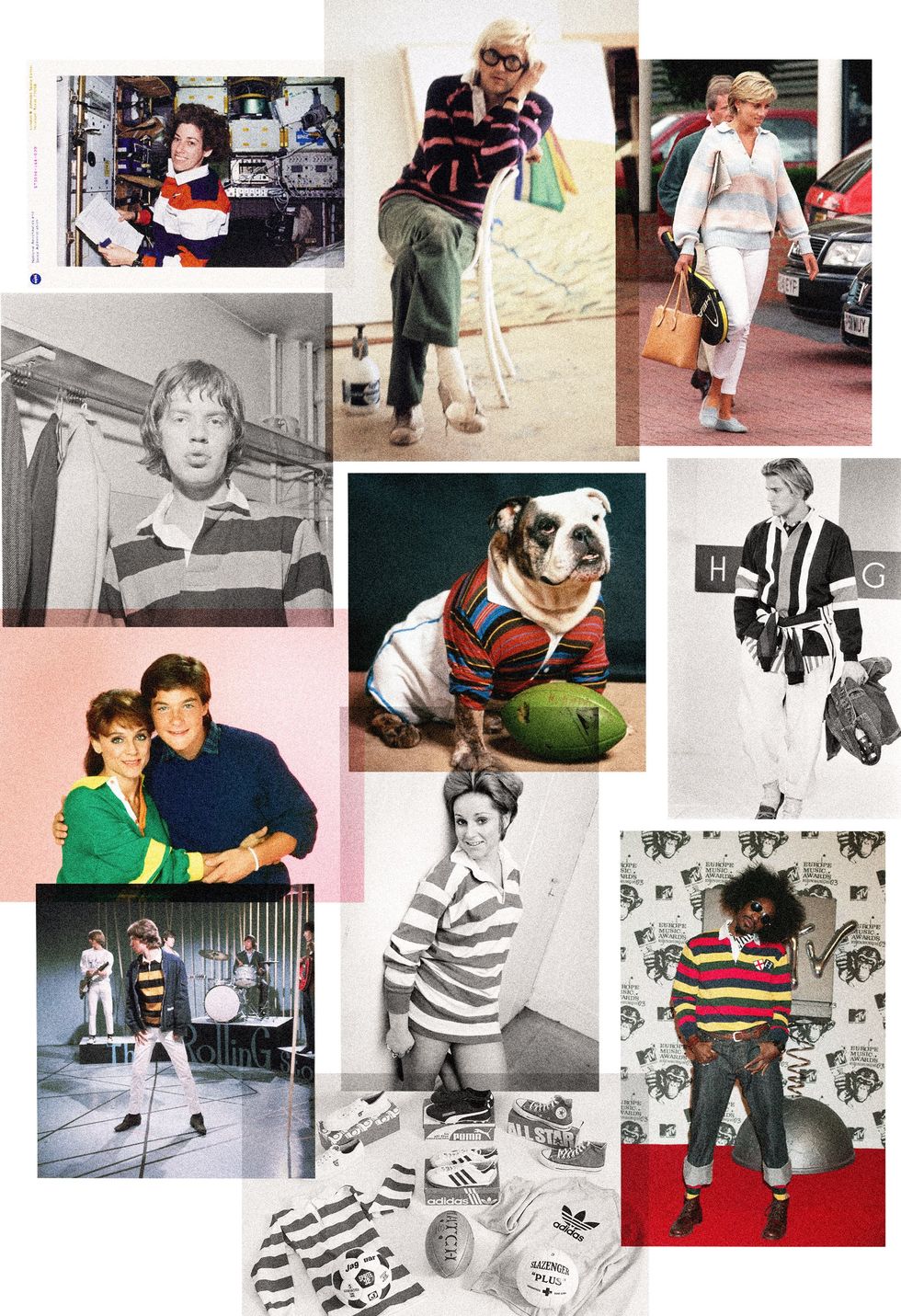

Mick Jagger and David Hockney both seemed to understand that intuitively. Neither one comes to mind when you think of prep icons, but they both wore rugby shirts habitually in a way that informs how they’re still worn now. Look at Jagger, wearing a yellow-and-navy-stripe rugby shirt underneath a pinstripe blazer, one hand on his hip and the other on Françoise Hardy’s shoulder. Or Hockney, in a pink-and-blue rugby shirt with a pair of dirty Converse, faded green trousers, and his signature round black glasses. They look good. Their rugby shirts feel like an authentic part of their personal style, and not like a piece of someone else’s personality they’re trying on to play a part. They’re also both British, so they actually know how rugby works, unlike most Americans. (Jagger’s father was a teacher at London’s Physical Education college in the ’50s and ’60s who also worked extensively with the British Sports Council.)

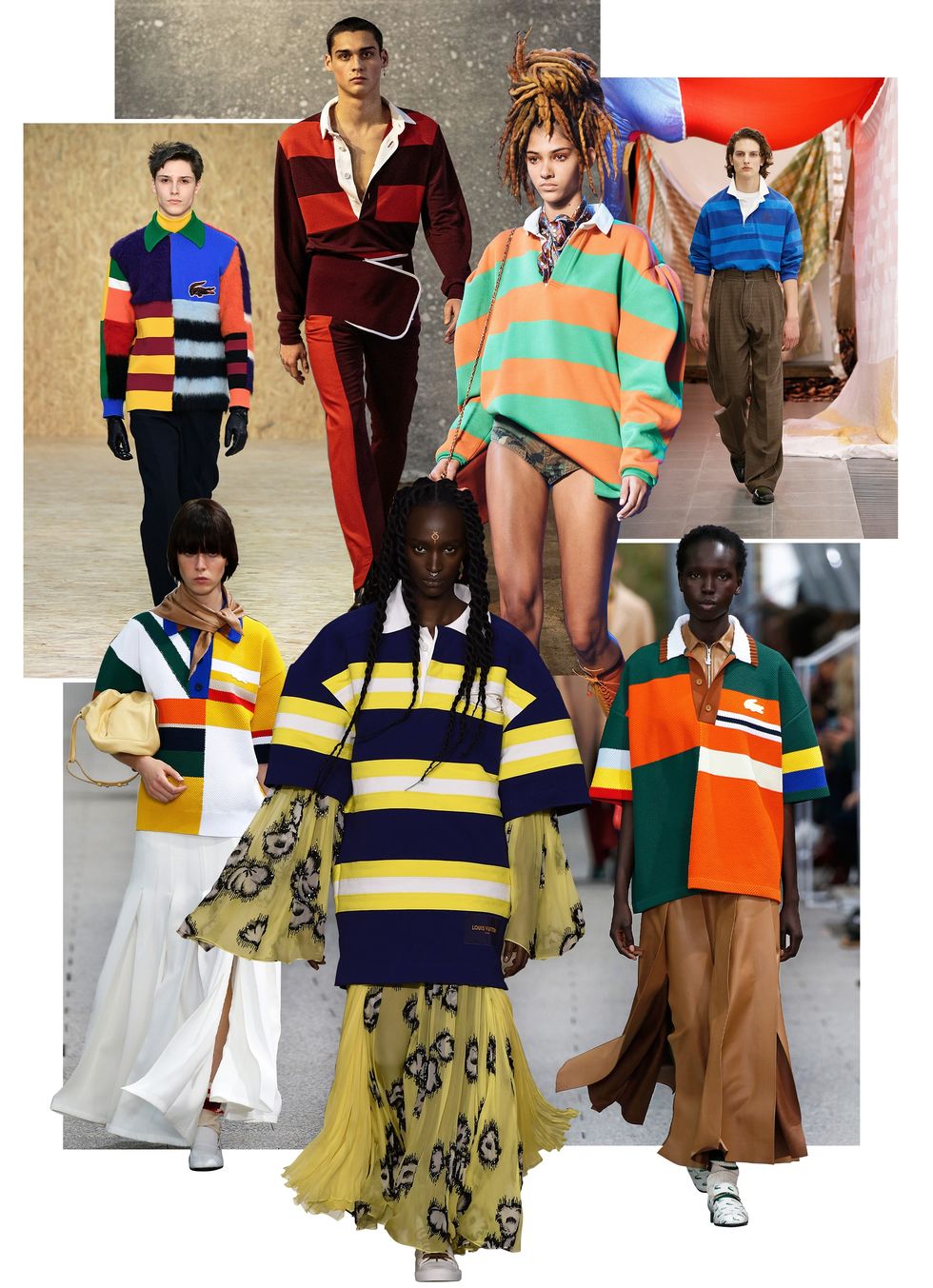

The rugby shirt is one of the only prep essentials that hasn’t morphed into something else. You can’t play tennis in a Miu Miu skirt the size of the belt, and you can’t comfortably ride a horse in a cropped Saint Laurent polo top. Sure, rugby shirts have been styled in interesting ways on the runway for years now (tucked into hot pants with six-inch platform boots for Marc Jacobs’s 2017 spring collection, and layered over a tiered, sheer maxi gown with a floral sweater tied around the waist at Louis Vuitton’s fall 2022 show), but the shirts themselves are still much like what you’d see on a rugby field. There’s a sustained authenticity to them that’s peerless in the prep universe.

Even Sevigny’s rugby, PMS embroidery and all, is really just two rugby shirts torn up and sewn back together. And maybe American designers’ restraint in recontextualizing the rugby shirts, and the appeal of the item to American shoppers, has to do with the fact that rugby is novel to those of us who don’t know what a scrum is. (Aside from being a great word, it’s the method of restarting play in the sport.) It doesn’t need to be transformed; it’s transformative on its own.

The rugby shirt represents prep style at its core, and yet it exists on an entirely different, muddier, field. Ralph Lauren, the king of prep, has famously said, “People ask how can a Jewish kid from the Bronx do preppy clothes? Does it have to do with class and money? It has to do with dreams.” And yet, even he saw rugby as representing a divergent dream: In 2004, when he wanted to design more rugby shirts, he launched an entirely separate line from Polo to do so, called Rugby Ralph Lauren.

The line was known for having an edgier distressed look at a lower price point to appeal to the 16-to-25-year-old customer. But the rugby shirt was the main draw, and each store had a full book of patches for shoppers to personalize their own. Trufelman remembers Rugby and its stores fondly. “It was so cool and so forbidden, because it was so goth and sexy. It was almost like the Hot Topic of preppy stores,” she says. Even the logo, featuring a skull and crossbones, felt uncharacteristic for Lauren. It screams, “This is Rugby, not Polo,” for the shopper who appreciates prep aesthetically but is worried about looking too much like a yuppie—probably much like the downtown types who lined up outside Big Ash. (Williams even told me when she’s sourcing rugbies, she is particularly keeping an eye out for the Ralph Lauren Skull and Bones 1923 style).

About that Y-word: Toward the end of our call, Sevigny asks me, “Do we even use the word yuppie anymore?” She’s right; we don’t really. Maybe that’s because yuppie is an insult directed at young professionals, and no one is really mad at people with nine-to-fives these days. Instead, the public’s ire is directed toward people with no jobs but seemingly unlimited funds. Nepo baby has replaced yuppie as a go-to insult when looking to attack someone’s sincerity. And when you consider how everyone is obsessed with authenticity right now, the rugby shirt’s charm is obvious. The preppy staple is so preppy it’s almost not preppy at all. It’s not pretentious. It’s a little unrefined. It’s the type of thing grown men put on to tackle each other and Sevigny throws on to be comfortable at the playground. And what could be preppier than that?

Tara Gonzalez is the Senior Fashion Editor at Harper’s Bazaar. Previously, she was the style writer at InStyle, founding commerce editor at Glamour, and fashion editor at Coveteur.