Growing up, Riz Ahmed would hear his family downstairs shout, “Asian!” and he’d rush to where they were gathered around the TV. Sanjeev Bhaskar in Goodness Gracious Me, Parminder Nagra in Bend It Like Beckham. In 2017, Ahmed was invited to address the British Parliament for an annual lecture about diversity — a funny and depressing turn of phrase — and noted that the continued misrepresentation of Muslims in film and television was a missed opportunity and dangerous. Inspired by his moving words, two Muslim film buffs then created “the Riz Test,” reproduced here from the official site:

If the film/show stars at least one character who is identifiably Muslim (by ethnicity, language or clothing) - is the character…

Talking about, the victim of, or the perpetrator of terrorism?

Presented as irrationally angry?

Presented as superstitious, culturally backwards or anti-modern?

Presented as a threat to a Western way of life?

If the character is male, is he presented as misogynistic? or if female, is she presented as oppressed by her male counterparts?

If the answer for any of the above is Yes, then the Film/ TV Show fails the test.

American movies have been answering “Yes” from the very start. In his book Reel Bad Arabs, author Jack Shaheen discusses the long history of misrepresentation, beginning at least in 1905 with The Palace of the Arabian Nights, directed by Georges Méliès. Here, as Shaheen describes, “Arabs ride camels, brandish scimitars, kill one another, and drool over the Western heroine.” Not much progress was made through the 1910s or 1920s. In the serials, Arabs might be slavers or terrorists — even pro-Nazi — and film’s first Arab woman terrorist was born in 1948 with Federal Agents vs. Underworld, Inc. The character, Nila, describes Westerners as “infidels” and sets off a bomb. Time and again, villainous Arabs threaten white women, from 1912’s Captured by Bedouins to The Pelican Brief in 1993.

Riz Ahmed Talked About How the Failure to Represent is Dangerous

Despite their variety in genre, these movies carry the same message as actual extremist propaganda. Noted for taking on increased, Hollywood-style production value, ISIS recruitment videos reach disenfranchised young Muslims with narrative structure like the Hero’s Journey. Playing on emotions, these “films” resonate with the target audience. Osama bin Laden’s worldview — or at least the one he projected — was informed by “a new crusade led by America against the Islamic nations.” In modern terms, he was playing identity politics. If counterprogramming is found primarily within America’s stranglehold on the international box office, what’s the message? “This is what we think of you.”

In 1990, Iraq invaded Kuwait and the American response was Operation Desert Storm. The ensuing Gulf War was the first conflict broadcast live on television, and the showmanship framing those bright lights in the sky would shape the next ten years of Hollywood. Before the turn of the century and after a long history of misrepresentation, what about the movies that a young Riz Ahmed and his family were watching, or that his friends or classmates saw before looking back at him?

‘True Lies’ Needed a New Kind of Villain

One of the key texts cited by Shaheen is True Lies, the 1994 action film directed by James Cameron and starring Arnold Schwarzenegger and Jamie Lee Curtis. It’s based on a French movie entitled La Totale!, which is also about a secret agent and his wife, but the antagonistic element is a gang of arms dealers. Granted, the villain is played by a Jewish-Algerian actor (Jean Benguigui), with the moniker of Sarkis, which is Lebanese. The American remake takes it a step further by inventing an Islamic extremist group called the “Crimson Jihad,” led by Salim Abu Aziz (Art Malik).

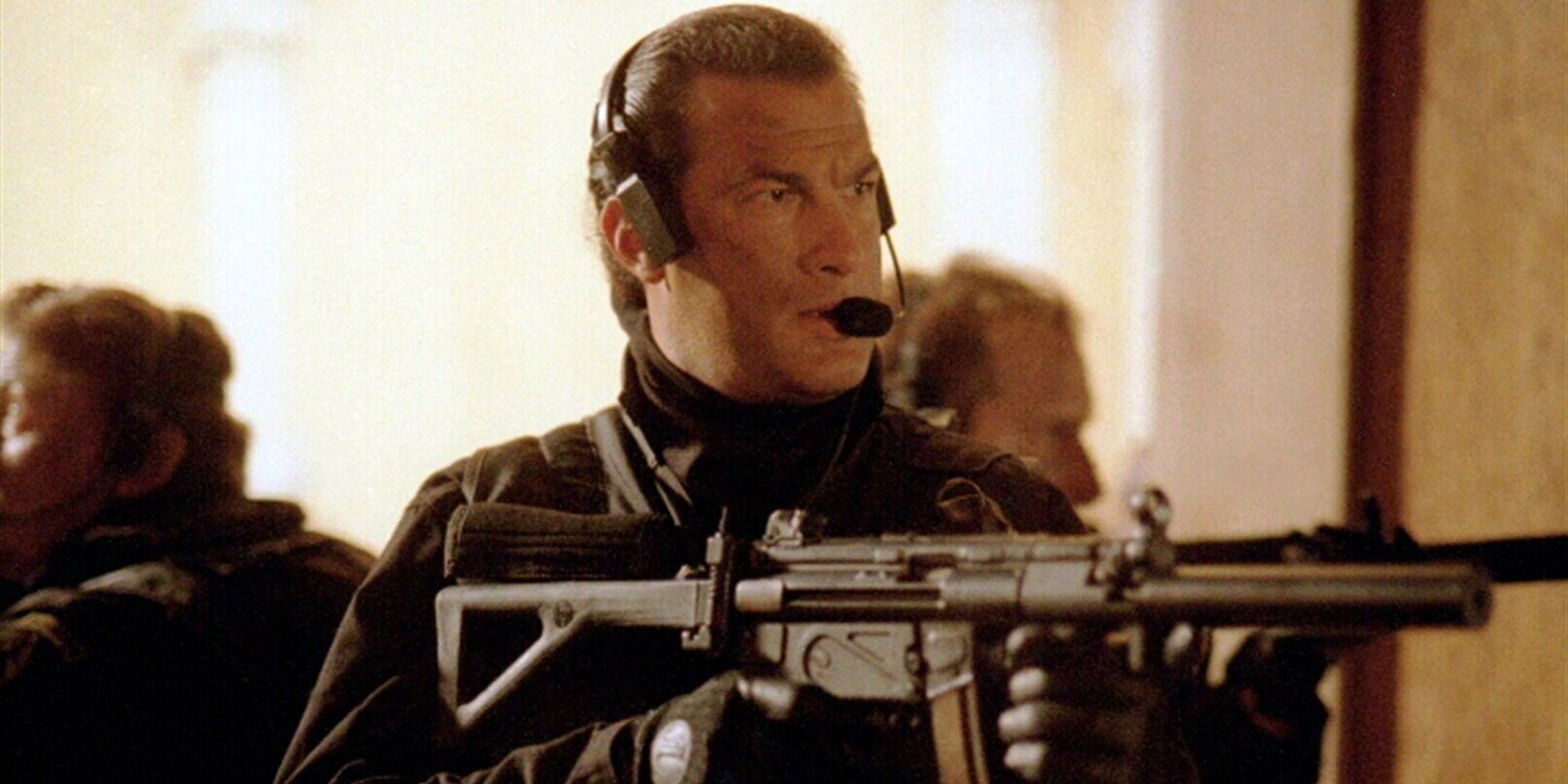

True Lies is also a comedy, and the Muslim villains are a running gag. They make silly faces in fight scenes or their camera runs out of battery in the middle of a threatening address. Aziz is killed in a particularly humiliating way, snagged on a missile and fired screaming at a helicopter. Arnold’s one-liner? “You’re fired.” Of course, such a villain is ever juxtaposed with Hollywood’s premier icon of masculinity. In a film that plays with gender roles, the family man triumphs over men proven lesser. It’s a thematic foundation deconstructed by another major action movie, 1996’s Executive Decision. This one, directed by Stuart Baird, stars Kurt Russell and Steven Seagal, about a commercial airliner hijacked by Islamic terrorists.

‘Executive Decision’ Fires its Own Arnold Schwarzenegger

The rumor surrounding Executive Decision is that Steven Seagal was fired off the project for any number of Steven Seagal reasons. His character, Lieutenant Colonel Austin Travis, is a Special Forces commander who suffers a surprise early death, but this was by design. The operation to retake the plane falls to Russell’s character, Dr. David Grant, an intelligence analyst who wears glasses. He does not immediately become John McClane, or more fittingly, President James Marshall of Air Force One, but rather listens to the surviving Special Forces team and acts as part of a unit in gathering intelligence and defusing a bomb. It’s yet another critical look at hypermasculinity from the writers of Predator (Jim and John Thomas), one that trades shootouts for sequences of suspense. The military violence represented by Travis is only one option, and a last resort at that.

Unfortunately, this best-case scenario for a now white-hot premise still requires that the villain, Nagi Hassan (David Suchet) invoke Allah and even get down on a prayer mat in the middle of his terrorizing. And with Grant and the Special Forces hidden in the plane, he spends most of his time menacing Jean, a female flight attendant (Halle Berry). He has no compunctions about hitting a woman, which would satisfy the fifth bullet point on the Riz Test. In the beginning of the film, Jean helps people to their seats, including those she doesn’t realize are terrorists. There’s a sequence where the camera pans over the faces of ethnic-looking passengers and a music sting plays. There’s one. And another! We’re being trained to spot them, with no criteria beyond visual appearance.

‘The Siege’ is Eerily Prophetic

The too-generic title Executive Decision refers to the president’s decision to shoot the plane down over the ocean before it delivers a payload. This ticking clock is the ultimate antagonist, and it’s true that Hollywood simply needs a villain to create drama. Yesterday it was the Nazis or the Soviets, and in the 1990s, it was Islamic extremists. With that film and the heightened fantasy True Lies, it almost feels arbitrary. Islam is a flavor. It isn’t until later movies like The Siege and Rules of Engagement that it becomes substantive. Directed by Edward Zwick and released in 1998, The Siege pits FBI agent Anthony Hubbard (Denzel Washington) against an escalating terrorist threat and one General William Devereaux (Bruce Willis), who takes the U.S. Army into Brooklyn under martial law.

Hubbard is the straight cop attempting to reconcile a secretive CIA agent (Annette Bening) and terrorism that can’t be understood. The bad guys who make up invisible cells want to free a captured leader who’s only ever referred to as “the sheik,” like a constant reminder of his religious otherness. And while the film is beautifully shot by Roger Deakins and well acted, with a complex script integrating morality about racism and even American culpability in attacks against it, the crisis is resolved when the last terrorist is shot to death. Sure, deploying the military inside the U.S. only proved to be an obstruction, and plenty of lessons were learned, but all that stuff about cause and effect is academic. Find the terrorist and stop him. All a movie like The Siege does is add, “but do it correctly.”

In the film’s climax, Hubbard has Devereaux arrested for the torture and murder of a Muslim suspect. He stands up for a guy named Tariq, and that’s a nice sentiment that nevertheless required Tariq’s torture and murder. Similarly, after Hubbard is injured by an explosion and gives an aggressive speech to his team about how the first 24 hours are the only 24 hours, the film cuts to an interrogation room where Khalil (Aasif Mandvi) is handcuffed and scared. Threatening him with a lit cigarette, Hubbard shouts “Tell me about the money!” in a perfect Jack Bauer growl. These are movies. They deliver us to these moments and require that we feel what the characters feel. In this case, it’s vengeance, to where violence is both logical and cathartic.

‘Rules of Engagement’ is the Next Great Islamophobic Movie

The terror targets in The Siege are a bus, a Broadway theater, an elementary school, and an FBI office. These are American institutions, even the humble bus, because Fox News viewers know that protestors are terrorists the moment they block traffic. In William Friedkin’s 2000 film Rules of Engagement, the Muslim threat first terrorizes a family. Where The Siege was pulling from real-world events like the Oklahoma City bombing, Rules of Engagement doubtlessly pulls from the 1979 embassy crisis in Tehran. Here, Yemeni protestors throw rocks and Molotov cocktails at the U.S. embassy, prompting a rescue mission headed up by Terry Childers (Samuel L. Jackson). When the protestors, all chanting and burqa-wearing, begin shooting at them, Childers orders his soldiers to fire back, and the ensuing massacre leaves 83 Yemenis dead.

What follows is a film almost too sickening to describe. When Childers is court-martialed and charged with murder, his old friend Hayes Hodges (Tommy Lee Jones) takes up his defense. Rules of Engagement turns out to be a courtroom drama no more complex than an episode of Bull, but twice as long. The actual question, posed by the film, is if the civilian massacre was justified. And the way it’s justified is if the protestors fired first, which we saw them do. The ostensible villain, National Security Advisor Sokal (Bruce Greenwood) destroys the evidence that the protestors fired first, which would’ve exonerated Childers. That’s the whole deal. So in court, the back and forth is repetitive on this point: “Did you warn the enemy?” the prosecutor demands. “We arrived in helicopters,” Childers responds. Oh, there you go.

The Riz Ahmed Test Asks for a Counter-Narrative

This is a surprising screenplay by Stephen Gaghan, who’d later work on films about perspective like Traffic and Syriana. It all comes down to whether or not the people judging Childers – including the audience – have ever experienced combat enough to say for certain they’d make a different call (they wouldn’t). “What would you have done in this situation?” is a pernicious question that anticipates any external attempt at accountability. In both this film and The Siege, Islamophobia is on the stand, but where the 1998 film has a hopeful message, this one is trying to exorcise American guilt over interventionism (it opens with a scene in the Vietnam War). And in the end, Childers is found not guilty of murder, because how can you kill someone who isn’t human? You think it’s bad, whatever’s going on “over there”? That’s funny. Pick up a rifle and go check.

Where True Lies and Executive Decision are entertaining thrillers, The Siege and Rules of Engagement are dire, dreadful movies. It’s almost like the more Islamophobic they are, the more susceptible to other flaws. And these are the movies that informed Riz Ahmed’s childhood before 9/11. They laid the structural and thematic groundwork for far worse in 24 and the stark, raving London Has Fallen, in which Gerard Butler kills and simultaneously taunts his Muslim enemy with the threat that America will be around for a thousand years. At the rate we’re going, it may take that long to fully purge our tendency toward stereotype, which is so much more than imagery but instinctive, powerful narrative.