Opinion: I’m so close after surviving a long trip from Venezuela. My asylum appointment is in days.

Last year, I decided to ask for an opportunity in the United States. I thought, if so many people have been given an opportunity, why not me?

Connell is a migrant in transit in Tijuana, Mexico. He was an emergency medical technician and first responder in his home country of Venezuela. This was translated from Spanish in an interview with a member of the editorial board.

Saving lives is what I do, and now I am in the mission of saving my own.

For 20 years, I was a rescuer, first responder, paramedic and firefighter in Venezuela, the country where I was born. I was trained by the government and ultimately part of a group that in emergency situations visited other countries to rescue people. Earthquakes in Haiti, floodings in El Salvador, miners trapped in Chile, I was there. However, working for the government in my country is not always a good idea. The massive corruption and the lack of justice are the worst combination to rule a country.

To many Americans, the complex, contentious issue of immigration centers around a policy question or a political agenda. To the immigrants who arrive at the southern border ever day, it’s their life.

I had a teenage son, and my wife and I had a newborn daughter, so I planned to escape my country and take them to a better place. Since I was a public official, the government had my passport. Lying about my real intentions, I asked my superiors for my document, and just because they trusted me, I was able to recover it for a couple of hours. That same night, we all ran away.

My wife, my kids and I established ourselves in Peru in 2017 where I found a job fishing. But the last five years — with five different presidents — have been politically unstable in that country, and that affects the economy. In a matter of months, my rent skyrocketed.

I then moved my family to Ecuador, and I stayed fishing in Peru. But I was living paycheck to paycheck and paying two rents in two different countries. I would work for two months and then visit my family for a couple of weeks, and that did not feel right.

Last year, I decided to ask for an opportunity in the United States. I thought, if so many people have been given an opportunity, why not me? That’s when I started drafting a plan.

It took me almost two months to prepare my 5-year-old princess. I told her that she needed to be ready because this time we would stop seeing each other for a longer period of time. After that, she would keep a close eye on me, especially if I was leaving home or reaching for my backpack. Right when she started forgetting about it, I knew it was time to leave.

I had my 30-pound rescue equipment on my back and $160 in my pocket. It took me three months to get from Ecuador to Tijuana. I had to walk, swim, ride boats, get through the jungle, avoid immigration checkpoints and so much more that I’m pretty sure I could write a book about it.

The first challenge was to survive the Darién Gap, a mountainous rain forest in the border between Colombia and Panama. For three days, I was trapped in a dense, mountainous jungle and swamp, filled with armed guerillas, drug traffickers and some of the world’s most deadly creatures. Spiders, snakes, scorpions, bushes with thorns, stiff corpses lying in abandoned tents or under the mud, and, during the night, the most intense darkness you will ever see.

Traveling with other migrants I met on my way, I was often mistaken for a guide. I kind of knew that would happen when others would see me wearing my official Venezuelan uniform with the “Protección Civil” (civil defense) sign and the equipment I had. After all, I am a rescuer, and I felt the responsibility of helping others when in need.

In the end, I’m not sure how many migrants I helped during the time it took us to get out of that jungle. I saved a couple from being drowned and I even had to suture someone’s arm. Once we were out and right before the group split apart, one migrant cut a plastic bottle in half and asked all for donations. “Colaboración,” he said. They gave me $650.

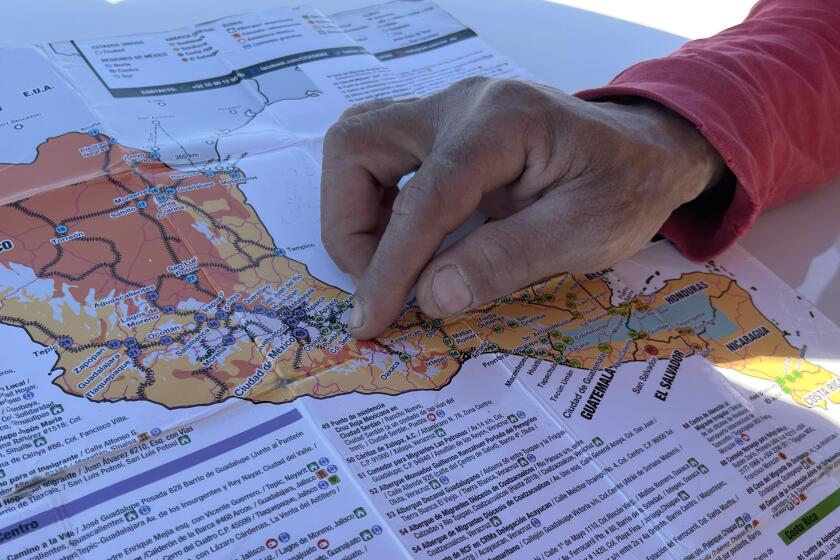

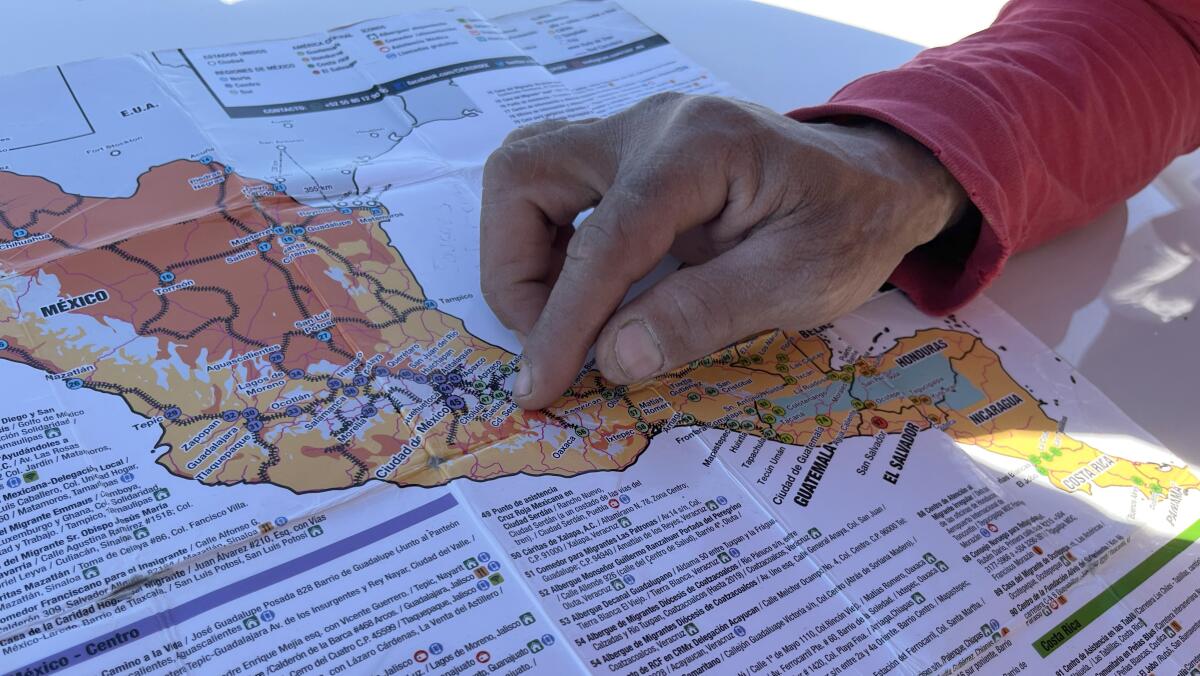

I decided to keep on with my journey to the U.S. and I was able to advance by riding buses, hitchhiking and asking others for help. I would look for the Red Cross or other humanitarian institutions everywhere I went. In Costa Rica, I received a map, but the local authorities took my rescue equipment, arguing that it was unsafe for me to carry it. They knew it was valuable. They robbed me.

I crossed Nicaragua, Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala to enter Mexico. The map had information about the distances between big cities and all the shelters that could receive me while in transit. I decided I wanted to make it to Tijuana.

I had no money and no cellphone when I arrived. I was hungry and desperate. Then, I saw a police car and asked for help. They brought me to the shelter in Campo Reforma, where I was able to apply with the Customs and Border Protection app and even though at first I had some issues, the application helped me schedule an appointment for Feb. 16. Many other migrants in the shelter say that the application has been a great way to apply to enter the U.S., but that there’s so much interest that the system constantly collapses.

The hard part comes when the evening starts and I feel hungry. Since I have no extra money to eat, I have to stay with what we all get at the shelter and sometimes, most of the time, that means rice with rice. Then I make time to video chat with my princess and tell her how much I miss her. I firmly believe that I will be able to cross to the U.S. and work rescuing others to send her and the rest of my family some money and their flying tickets. Because I don’t want them to cross the Darién Gap.

Right before leaving Ecuador, I took my princess for ice cream and I also made her a promise. The next time we get to see each other, I’ll hand her a ticket to Disney World.

Get Weekend Opinion on Sundays and Reader Opinion on Mondays

Editorials, commentary and more delivered Sunday morning, and Reader Reaction on Mondays.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.