A world taken over by fungal infections, with no vaccine available: It sounds like the plot of post-apocalyptic show The Last of Us, but it could become our reality as climate change makes diseases caused by fungi, like valley fever, better at spreading.

Valley fever is usually only contracted in the southwestern U.S. states, with the majority of all U.S. cases occurring in Arizona and California, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

However, valley fever and other fungal infections are being found increasingly far outside of their usual ranges, and climate change might be to blame.

"Cases of valley fever have been rising, and there are regions of the U.S. that have not been considered endemic for the disease, such as eastern [Washington] state, that are now seeing locally acquired cases," Bridget Barker, a valley fever expert and associate professor at Northern Arizona University, told Newsweek.

Valley fever is caused by the Coccidioides fungus, which lives in dry soils. Like most fungi, it produces spores that become airborne, which can infect humans when we breathe it in.

"If soil contaminated with the fungus is disturbed (e.g. by digging into it, or by a wind storm), this can blow spores into the air that we inhale into our lungs," Rebecca Drummond, a fungal immunologist and associate professor at the University of Birmingham in the U.K., told Newsweek.

Each year, around 80 people in California alone die from valley fever, with over 1,000 becoming hospitalised from the infection. Across the U.S. as a whole, around 200 people die from the fungus annually.

Symptoms of valley fever include a cough, fever, tiredness, headache, night sweats, muscle and joint aches, and upper body or leg rash, according to the CDC.

"Most people who inhale the spores never get sick, but a small number will get lung problems caused by the fungus growing in the lung," Drummond said. "Other people may get serious infection that spreads to other organs outside of the lung. Most people who get serious infection do so because their immune system is damaged in some way (e.g. by an inherited immune disorder or taking drugs that prevent the immune system from working properly)."

The disease becomes dangerous if the infection moves beyond the lungs, such as to the liver, spleen, skin, bone, or joints.

Valley fever caused By C immitis Symptoms of Valley Fever (Coccidioidomycosis)

— MEDICOSE FEVER 🐦 (@MEDICOSEFEVER) January 25, 2023

Fatigue (tiredness)

Cough.

Fever.

Shortness of breath.

Headache.

Night sweats.

Muscle aches or joint pain.

Rash on upper body or legs. pic.twitter.com/U8UHWpetH9

"The worst is dissemination to the brain, which requires lifelong antifungal treatment—and that has its own set of side effects," Barker said. "Disseminated disease to skin and bones/joints can be extremely painful causing a condition referred to in the old literature as "desert rheumatism" and can be misdiagnosed as bone cancer. Even the lung form can be misdiagnosed as lung cancer, because it creates nodules that can be seen on MRI/CT scans."

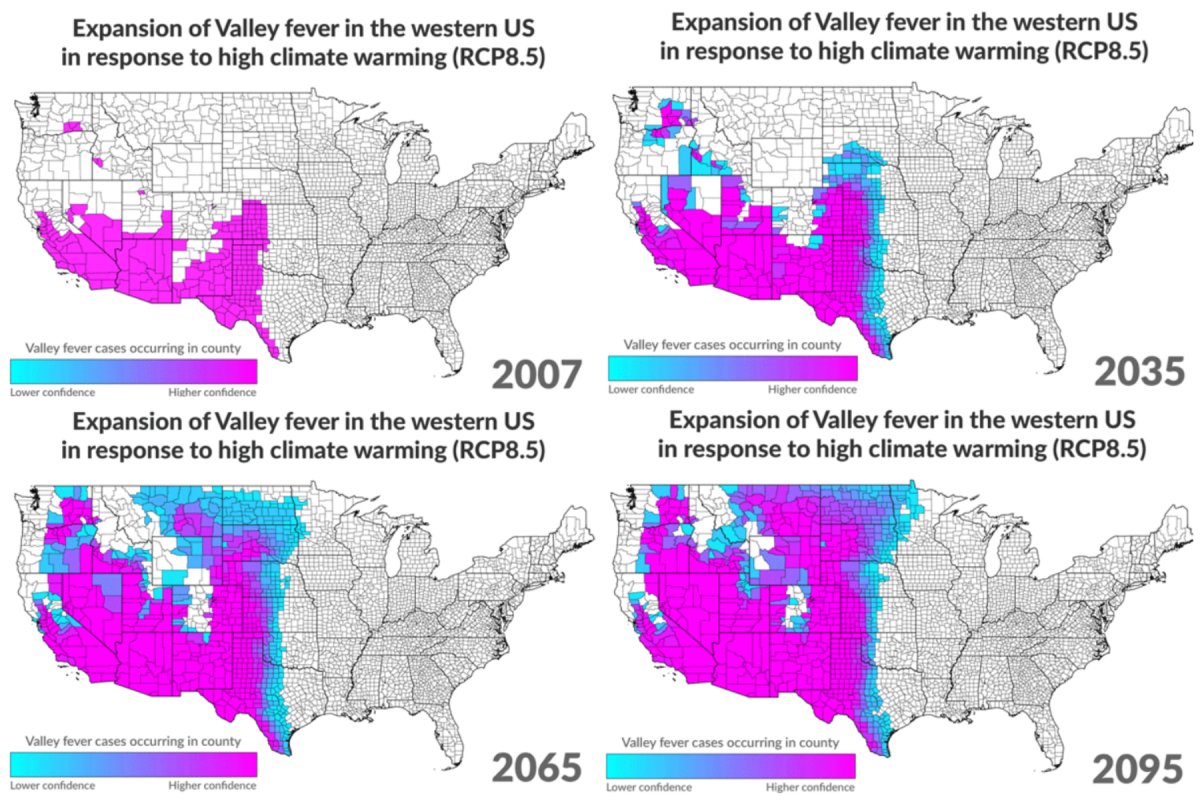

Cases of valley fever are increasing, and moving outside of its traditional range, with one study published in the journal GeoHealth predicting that the range of valley fever could spread east to the Great Plains and as far north as Canada before the end of the century, due to climate change.

"These fungi live in the soil of dry areas (e.g., deserts) and are found in parts of Central America, South America, and Southwestern U.S.," Antonis Rokas, a professor of biological sciences and biomedical informatics at Vanderbilt University, told Newsweek. "However, climate change modeling suggests that regions where the disease is endemic could increase by 50% during this century."

The changing climate is drying out huge portions of the U.S. southwest and beyond, making the land ideal for the growth of valley fever. The post-drought rainfall that will follow will also make for good conditions for the fungus.

"The fungus is adapted to hot and dry conditions, seems to positively respond to extended drought followed by heavy rain, which is the climate prediction for the western U.S. This is why we are concerned and think that the cases are increasing," Barker said.

The future of fungal infections like valley fever spreading more widely is highly concerning, as we are far less adept at treating and vaccinating against fungi than we are against bacteria or viruses.

"I think we should be worried about fungal infections generally, because we are much less equipped to deal with these infections than other types," Drummond said. "There are no fungal vaccines available, and antifungal drugs are more limited than antibiotics. We have also seen increasing rates of antifungal drug resistance in recent years. This means that fungal infections are hard to treat and valley fever is no exception. We desperately need more research into fungal infections to help us develop new and better treatments for these diseases."

Similar adaptations may occur in other species of fungal infections, which could also be catastrophic if that fungus is one that can infect humans and impact us to a large degree. In the HBO show The Last of Us, based on a video game of the same name, an ant-infecting, behavior-altering species of Ophiocordyceps adapted to live at human body temperatures, and ended up spreading rapidly through the human population.

"As the planet warms, this may mean that fungi are forced to adapt and become better equipped to grow in the hotter temperatures," Drummond said. "Climate change also means that more dramatic weather events can occur, like dust storms, which blow the fungus in the soil more often and greater distances, exposing more people and causing more infections."

Is there a health issue that's worrying you? Do you have a question about fungal infections like valley fever? Let us know via health@newsweek.com. We can ask experts for advice, and your story could be featured on Newsweek.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Jess Thomson is a Newsweek Science Reporter based in London UK. Her focus is reporting on science, technology and healthcare. ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.