How America Lost Its Grip on Reality

Life in the metaverse is fueling conspiracies across America.

This is an edition of The Atlantic Daily, a newsletter that guides you through the biggest stories of the day, helps you discover new ideas, and recommends the best in culture. Sign up for it here.

In her cover story for the March issue of our magazine, the staff writer Megan Garber argues that Americans are living in a kind of “metaverse,” where the line between entertainment and reality is blurrier than ever. That lack of clarity could be hastening the nation’s descent into conspiracy.

But first, here are three new stories from The Atlantic.

“I’m a Real Person”

From Americans’ bottomless appetite for true crime to the camera-mugging antics of January 6 insurrectionists, “the metaverse has leaped from science fiction and into our lives,” writes Megan Garber. Entertainment has become so immersive that it not only dovetails with real life but also absorbs it, rendering ordinary Americans the “main characters” of daily dramas that play out, often, online. Instead of fostering a sense of interconnectedness, life in the metaverse has fed mistrust in institutions and in one another.

The metaverse, in other words, is fertile ground for conspiratorial thinking.

Garber writes:

Recall how many Americans, in the grim depths of the pandemic, refused to understand the wearing of masks as anything but “virtue signaling”—the performance of a political view, rather than a genuine public-health measure. Note how many pundits have dismissed well-documented tragedies—children massacred at school, families separated by a callous state—as the work of “crisis actors.” In a functioning society, “I’m a real person” goes without saying. In ours, it is a desperate plea.

This kind of conspiratorial thinking has supercharged political polarization in the U.S., the Atlantic contributing writer Brian Klaas explained last month:

Other countries, including the U.K., have polarization. America has irrational polarization, in which one political party has fallen under the spell of conspiratorial thinking. Polarization plus this conspiracist tendency risks turning run-of-the-mill democratic dysfunction into a democratic death spiral. The battle for American democracy will be a battle over reality.

Not helping matters is the enduring sway of Donald Trump within the Republican Party, whose base has molded itself in his likeness. In 2020, our editor in chief Jeffrey Goldberg noted the troubling implications of the then-president’s attraction to conspiracy:

Trump does not defend our democracy from the ruinous consequences of conspiracy thinking. Instead, he embraces such thinking. A conspiracy theory—birtherism—was his pathway to power, and, in office, he warns of the threat of the “deep state” with the ferocity of a QAnon disciple. He has even begun to question the official coronavirus death toll, which he sees as evidence of a dark plot against him. How is he different from Alex Jones, from the conspiracy manufacturers of Russia and the Middle East?

He lives in the White House. That is one main difference.

... Nonsense is nonsense, except when it kills. And conspiracy thinking, especially when advanced by the president of the United States, is an existential threat.

A broad increase in conspiracism may also be behind the recent uptick in anti-Semitic harassment and violence. As the Atlantic staff writer Yair Rosenberg wrote last year, “Unlike many other bigotries, anti-Semitism is not merely a social prejudice; it is a conspiracy theory about how the world operates.”

Rosenberg continues:

The fevered fantasy of Jewish domination is incredibly malleable, which makes it incredibly attractive. If Jews are responsible for every perceived problem, then people with entirely opposite ideals can adopt it. And thanks to centuries of material blaming the world’s ills on the world’s Jews, conspiracy theorists seeking a scapegoat for their sorrows inevitably discover that the invisible hand of their oppressor belongs to an invisible Jew.

Rosenberg’s theory of anti-Semitism-as-conspiracy points to the basic appeal in applying a narrative arc to real life. Stories help explain the hard-to-understand, if not the unexplainable. In a 2020 Atlantic article, our editor Ellen Cushing vividly recalled her own teenage foray into conspiracy thinking, reflecting on the sense of reassurance that this mindset can provide:

Conspiracy thinking is incredibly compelling. It promises an answer to problems as small as expired light bulbs and as big as our radical aloneness in the universe. It is self-sealing in its logic, and self-soothing in its effect: It posits a world where nothing happens by accident, where morality is plain, where every piece of information has divine meaning and every person has agency. It makes a puzzle out of the conspiracy, and a prestige-drama hero out of the conspiracist. “The paranoid spokesman sees the fate of conspiracy in apocalyptic terms,” the historian Richard Hofstadter wrote in his seminal 1964 essay, “The Paranoid Style in American Politics.” “He is always manning the barricades of civilization.” What Hofstadter declined to put a finger on is the intoxicating feeling of having insider knowledge about the fate of the world, or at least believing you do.

Related:

Today’s News

- Federal Reserve officials held their first meeting of the year and raised interest rates by a quarter of a point.

- The funeral of Tyre Nichols, a 29-year-old Black man who was fatally beaten by police, was held this afternoon in Memphis. Reverend Al Sharpton delivered the eulogy.

- The FBI conducted a planned search of President Joe Biden’s vacation home in Rehoboth Beach, Delaware, and did not find any classified documents, according to Biden’s personal attorney.

Dispatches

- The Weekly Planet: The most famous climate goal is woefully misunderstood, Emma Marris writes.

- Up for Debate: Conor Friedersdorf asks for your thoughts, cultural memories, or personal experiences related to the weight-loss industry.

Explore all of our newsletters here.

Evening Read

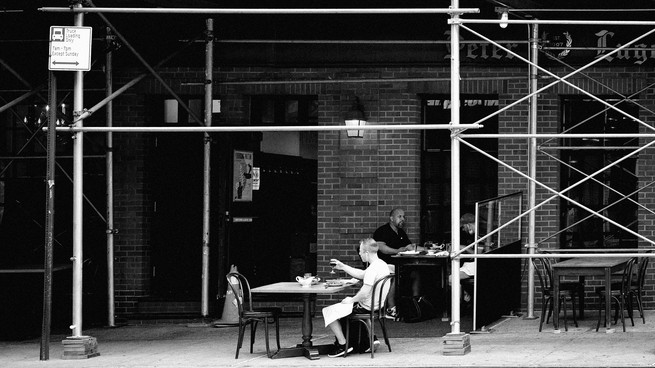

Outdoor Dining Is Doomed

By Yasmin Tayag

These days, strolling through downtown New York City, where I live, is like picking your way through the aftermath of a party. In many ways, it is exactly that: The limp string lights, trash-strewn puddles, and splintering plywood are all relics of the raucous celebration known as outdoor dining.

These wooden “streeteries” and the makeshift tables lining sidewalks first popped up during the depths of the coronavirus pandemic in 2020, when restaurants needed to get diners back in their seats. It was novel, creative, spontaneous—and fun during a time when there wasn’t much fun to be had. For a while, outdoor dining really seemed as though it could outlast the pandemic. Just last October, New York Magazine wrote that it would stick around, “probably permanently.”

But now someone has switched on the lights and cut the music. Across the country, something about outdoor dining has changed in recent months. With fears about COVID subsiding, people are losing their appetite for eating among the elements.

More From The Atlantic

Culture Break

Read. One teacher’s approach will change the way you read, or reread, The Great Gatsby.

Watch. You still have time to catch up on the Oscars contenders you need to see.

P.S.

Some of the passages I cited in today’s Daily were originally published as part of “Shadowland,” a 2020 Atlantic project about conspiracy thinking. Megan Garber has another story in that series, titled “The Paranoid Style in American Entertainment,” that makes for a great complementary read to her metaverse feature. I recommend reading one after the other, then letting it all sink in.

— Kelli

Did someone forward you this email? Sign up here.

Isabel Fattal contributed to this newsletter.