In 1968, then-Chief Justice Earl Warren went to the White House to let President Lyndon B. Johnson know that he was planning to retire. He explained that he wanted to be replaced by a liberal. Johnson, who was also on his way out of office, wanted to secure the chief justice’s seat before his term ended. He tapped Justice Abe Fortas for the job. Fortas, who had once represented Clarence Gideon in Gideon v. Wainwright, a landmark lawsuit finding a Sixth Amendment right to counsel for indigent criminal defendants, had been a stalwart of the Warren Court’s progressive wing since he was seated in 1965. Republicans in the Senate immediately launched a campaign to discredit Fortas as a potential chief, partly because he was a close adviser to Johnson, even after being confirmed at the court, and partly because he sided with integrationists and criminal defendants from the bench, and was on the wrong (right?) side in hotly contested dirty movie cases. All this was accompanied by a heaping side of antisemitism at the prospect of seating the first Jewish chief justice.

It’s not that there were no issues with Fortas. Eventually it surfaced that he had some sketchy financial arrangements that included a lucrative lectureship at American University, funded by contributions raised by wealthy former law clients. And so, his nomination stalled in a Senate filibuster, Fortas remained on the court as an associate justice.

In Adam Cohen’s superb 2021 book, Supreme Inequality, he describes what happened when Richard Nixon took office after the 1968 election. Nixon, determined to remake the court, immediately went on offense. His first target? Securing Fortas’ resignation. “Nixon cleared his desk of other work to focus on getting Fortas off the Court,” according to his chief domestic policy advisor, John Ehrlichman. John Dean, who would later become White House counsel, described a Nixon Justice Department hard at work “spreading rumors and leaking … information” to a reporter at Life magazine. One of the things the DOJ began digging into was Fortas’ relationship with Louis Wolfson, a wealthy financier and supporter of progressive causes. Fortas was serving on Wolfson’s family foundation while he sat on the court, and accepted a $20,000 annual stipend to do so. But other justices, writes Cohen, had similar arrangements, and this violated no rule or law. Plus, when Wolfson was indicted by the SEC, Fortas quit the foundation and returned the money. Again, no ethics rules at the court meant no ethics violations.

That didn’t matter—John Mitchell, Nixon’s attorney general, truly smelled blood in the water. His DOJ falsely told the Life magazine reporter that the department had opened a criminal investigation into Fortas. When the question of whether the DOJ even had the authority to investigate a sitting justice arose, a young William Rehnquist, then assistant attorney general, produced a memo for Mitchell finding that Fortas could be prosecuted as a sitting associate justice.

Mitchell threatened to reopen a closed case against Fortas’ wife, for which she had already been cleared. Republicans in Congress wanted to consider impeachment. But Nixon wanted something faster.

Nixon hosted a black-tie dinner at the White House to honor Warren as he was stepping down as chief justice. It was a party Warren later described as “the most thrilling social event of my half century of public life.” A few weeks after the event, the DOJ was pressing Wolfson to testify that Fortas had done something improper for him. Wolfson refused. No matter. As John Dean would later write:

On May 7, Mitchell’s long black limousine pulled quietly into the basement garage of the Supreme Court Building, and the attorney general was whisked through the building for a confidential session with the chief justice. Mitchell had not met Earl Warren before the White House dinner a few weeks earlier, but the glow of good feeling still radiated from that evening.

Mitchell’s visit to Earl Warren at the high court featured confidential documents, including Fortas’ contract with the Wolfson Foundation. According to Cohen, “Nixon and Mitchell knew that Warren was fiercely protective of the Court and of his own legacy. He would not want to end his tenure with a major ethics scandal, and he certainly would not want one of his justices charged with a federal crime.” When Warren saw the documents, he reportedly told his secretary, referring to Fortas: “He can’t stay.”

On May 12, the DOJ delivered more documents to Chief Justice Warren, signaling that it was still investigating Fortas. The New York Times criticized Mitchell for “an ugly squeeze play by the administration to force Fortas off the bench,” but it did nothing to deter his efforts. On May 13, Warren convened a meeting of the justices to go over the DOJ’s evidence against Fortas. Fortas resigned the next day. As Dean would later write:

By the time Fortas presented his plight to his brethren, he had made the decision to retire. More remarkably, he got no sympathy from his colleagues. They treated him as a condemned man. Not one protested that he had broken no law. Not one acknowledged that other justices at the conference table had accepted fees from charitable foundations. Not one suggested that Fortas should stay and fight. Richard Nixon and John Mitchell had intimidated them all.

Historians largely agree that Fortas might have brazened it out. But as he told his former law partner Paul Porter, he had “had it.” As Cohen describes it, many factors led Fortas to step down, although the evidence against him was both thin and indirect. It’s reasonable to think that it was the turning of Warren, his former ally, and his brethren that may have been decisive.

Warren had done “the job well,” according to Nixon’s policy advisor, Ehrlichman. Indeed, Ehrlichman wrote in his memoir that Warren “had persuaded Abe Fortas to resign, and suddenly we had two vacant seats on the court.” A spontaneous drinks party broke out in Attorney General Mitchell’s office when they learned of Fortas’ resignation. Nixon even called in to congratulate them.

We may never know if Fortas’ ethical issues rose to the level of demanding a resignation (though Cohen and Penn State’s Bruce Allen Murphy both suggest, after significant research, that they did not). But we do know two things in hindsight: Fortas’ departure was a factor in the eventual collapse of the progressive Warren Court. And so succumbing to Nixon and Mitchell’s pressure campaign to oust him may have been the single biggest mistake of Earl Warren’s career.

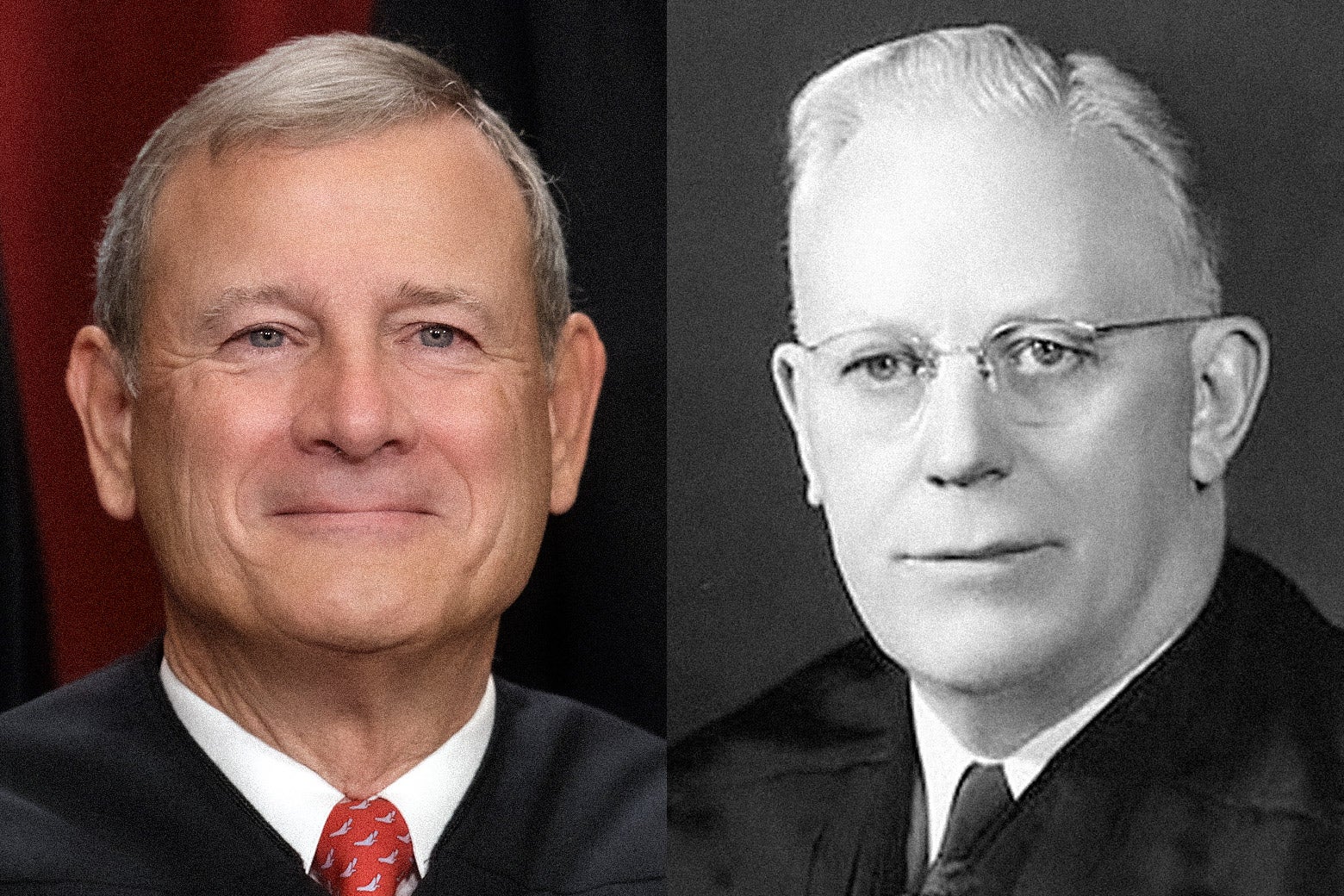

I rehearse this story in part because it’s the answer to the question that hangs in the ether today as news continues to pile up about purported ethics violations at the Supreme Court. Those violations include, but are not limited to: money from interested parties in cases securing access to the justices by way of the Supreme Court Historical Society; the generalized grossness of learning that former Homeland Security Secretary Michael Chertoff—paid by the court for security—signed off as an independent expert on the generalized grossness of the Dobbs leak investigation; the continued conviction at One First Street that the Thomases’ marriage is somehow less problematic ethically than, say, the fact that Fortas’ wife had once been cleared of a crime. The legitimacy of the institution is once more a topic of heated national debate, with stories coming out every day—today’s actually focuses on the possibly unethical activities of the chief justice’s own wife. But this time the court opts not to weigh in.

I was reminded of the Cohen account in part because it offers an answer to the question of whether the chief justice is indeed wholly powerless to probe ethics questions among his colleagues, and also to the ancillary question of whether the chief justice is somehow honor-bound to pretend ethics issues don’t exist. It’s not at all clear that Justice Warren did the right thing in meeting secretly with Mitchell, or swanning around the East Room of the White House in a tux, or convening his brethren to form an impromptu Star Chamber at which Fortas, unable to defend himself any longer, felt forced to resign. Indeed one lesson of this story could be interpreted to mean that when a justice violates the court’s imaginary ethics rules, that justice should be left alone altogether—after all, what the Warren Court allegedly did to Abe Fortas was both excessive and improper.

But there is a second lesson from this story, one that holds that it is a black eye to everyone in the building when a justice behaves unethically, or even, as was the case with Fortas, appears to behave somewhat unethically in the eyes of the public. This lesson suggests that it’s incumbent on the chief justice and the associate justices to insert themselves into those conversations because the legitimacy of the whole entire court is on the line. More urgently, in that telling, once the chief justice and the associate justices insert themselves into those conversations, the behavior will stop. It can stop. It is certainly eminently stoppable. That, too, is the lesson of Justice Fortas.

In other words, it’s not at all clear that the muted cry that nothing can be done about whatever it is that is happening inside the Supreme Court these days is even true. The sorry tale of how Warren helped push out fellow liberal Abe Fortas suggests that the justices can indeed use their informal powers to check their colleagues if they are sufficiently worried about public disapprobation and condemnation. More than half a century later, the Fortas story is certainly interesting as a roadmap to soft power and the internal policing of judicial misconduct. It is even more powerfully a lesson in how and why, 50 years later, in the face of far more consequential and public ethical crises, the choice to do nothing is held out as the only viable play.