Editor’s Note: Lev Golinkin writes on refugee and immigrant identity, as well as Ukraine, Russia and the far right. He is the author of the memoir “A Backpack, a Bear, and Eight Crates of Vodka.” The opinions expressed in this commentary are his own. View more opinion on CNN.

In December, a German court made headlines when it convicted a 97-year-old former Nazi concentration camp secretary for her role in the murder of over 10,000 people during the war. The decision to pursue a crime 77 years after the end of World War II is the latest in Germany’s assurance of its utmost commitment to atoning for the Holocaust.

Across the United States and Europe, the Holocaust is rapidly fading from memory, but Germany is trying to prove that it will never forget. In addition to prosecuting Nazis, the country has been a leader in ensuring Holocaust education is a core part of the school system. It also has stringent laws combating Holocaust denial. And just last week, the German parliament commemorated Nazi victims persecuted for their sexual or gender identity.

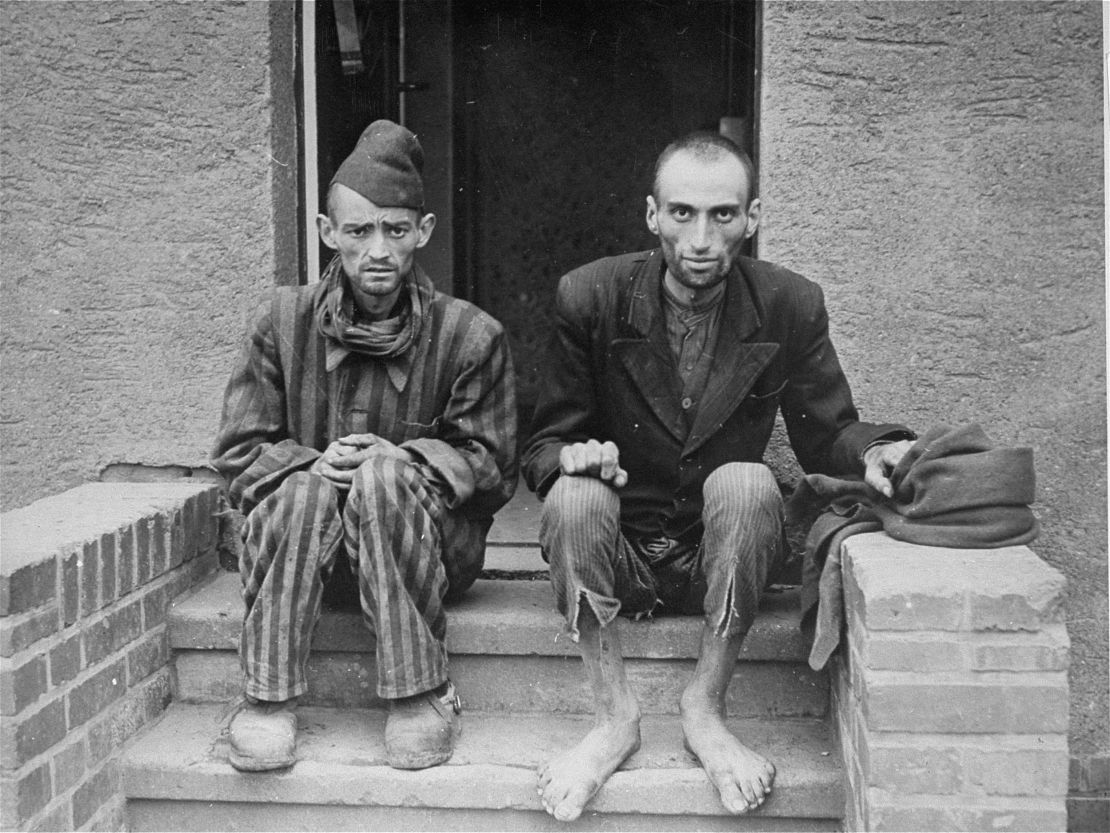

However, over the past several decades, Germany has been quietly betraying the memory of Holocaust victims by naming streets, schools and medical facilities in honor of Nazi Party members and SS officers – men who used slave labor from concentration camps, armed the Third Reich and directly enabled the genocide.

A country can’t claim to fully respect Holocaust remembrance while simultaneously glorifying the people who made the Holocaust possible. And Germany has been long overdue in facing this hypocrisy.

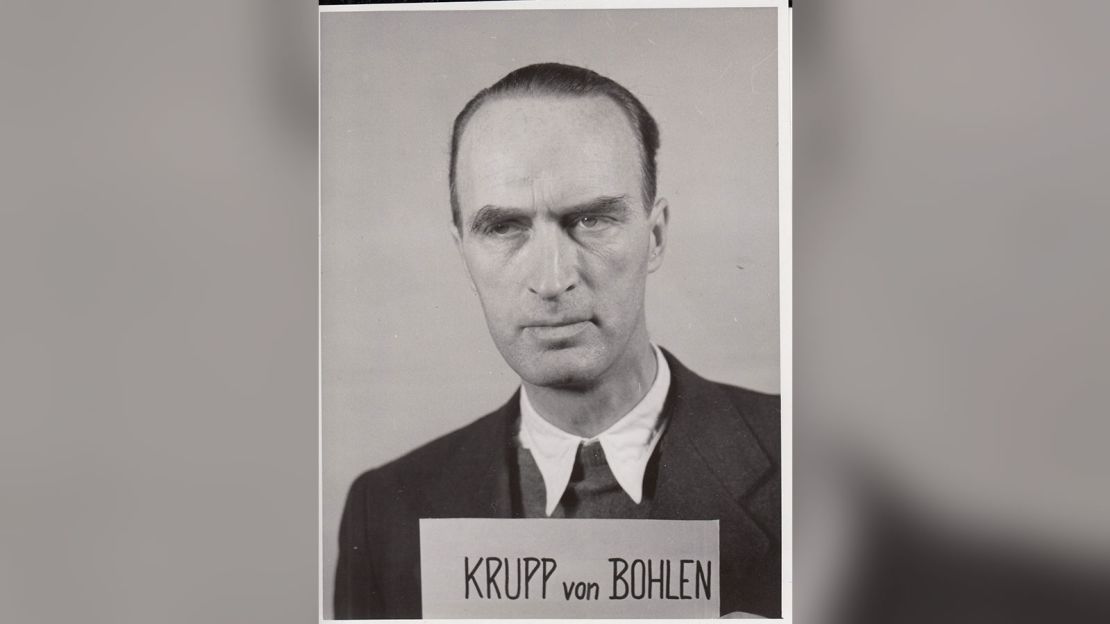

Money solves a lot of problems, even – or perhaps especially – if one’s a war criminal. In 1948, a Nuremberg tribunal convicted industrial magnate Alfried Krupp of war crimes and crimes against humanity. Krupp’s empire not only armed Nazi Germany, but had around 100,000 slave laborers, including concentration camp inmates, and a factory at Auschwitz.

Krupp ended up serving a total of six years before his sentence was commuted, and he was given back his seized assets – much of which was procured off of war and genocide. Before his death in 1967, he bequeathed his fortune to what became the Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach Foundation, which commenced pumping millions into charitable causes.

Unsurprisingly, many of its projects ended up honoring Krupp – transforming him from a convicted war criminal to visionary philanthropist whose name graces a college, institute, hospital, nursing home and concert hall. As well as numerous university scholarships and endowments financed by his foundation.

Last year, a Jacobs University Bremen spokesperson was refreshingly blunt in telling me the school had received 10 million deutschmarks from Krupp’s foundation, “and with this donation the name ‘Alfried Krupp College’ has been given.”

But Krupp is hardly an isolated case. Klaus Bahlsen was a Nazi Party member who funded the SS – the party’s military wing responsible for orchestrating the Holocaust. During the war, Bahlsen and his two brothers ran a biscuit conglomerate that had more than 2,150 slaves in a factory in Nazi-occupied Ukraine; additionally, more than 700 mostly Polish and Ukrainian women were forcibly sent to labor for the Bahlsens in Hanover.

Bahlsen, like Krupp, established a charity that pours millions into public works, many of which are named after him and done in partnership with municipal governments. Bahlsen’s biography on the Rut and Klaus Bahlsen Foundation’s webpage makes no mention of his Nazi membership or use of slave labor. (Klaus’ wife, Rut Bahlsen – the foundation’s other namesake – wasn’t affiliated with the Nazis as far as it is known).

Indeed, the historical whitewashing has been so blatant that, in 2019, the heiress to Bahlsen’s fortune indignantly asserted her family’s slaves were treated “well.” After international condemnation, she issued an apology.

Sadly, it doesn’t stop with Bahlsen either. Friedrich Flick, another magnate convicted of crimes against humanity in Nuremberg, has a foundation and several streets bearing his name. Multiple cities have streets honoring Ferdinand Porsche, Hitler’s favorite car designer whose Volkswagen plant murdered an estimated 350 to 400 infants. (Although Porsche was detained by the Allies, he was never tried for war crimes. As the US Holocaust Memorial Museum puts it, “Justice was scant for Volkswagen perpetrators.”)

And, in 2015, the city of Coburg named a street for Nazi war profiteer Max Brose, who also has an eponymous foundation, despite an outcry from Germany’s main Jewish organization.

Meanwhile, Hamburg celebrates the Nazi Kurt Körber, technical director of Dresden Universelle-Werke, which had up to 3,000 forced laborers during the war, including at least 700 female concentration camp inmates. Hamburg, which has been lavished with money by Körber’s foundation, has a school, street and sprawling new center named for him.

These are just some examples: Germany is riddled with places named for other Nazi Party members as well as antisemitic academics, authors, composers and poets who vociferously welcomed Adolf Hitler’s rise.

How does one defend the indefensible? Mostly by obfuscation and deception.

Over the past decade, numerous German cities, including Berlin, Hamburg, Hanover, Munich and Dusseldorf, commissioned panels to identify problematic place names.

Around the same time, some companies and foundations named after Nazis hired historians to dig into their honorees’ pasts. The resulting reports provide the illusion of public and private leadership taking steps to confront Germany’s Third Reich legacy.

Unfortunately, in many of these cases, the place names flagged by the reports remain unchanged and the corporations continue memorializing their Nazi founders. Indeed, by brazenly publishing these reports, the cities and foundations make it clear they know exactly who they’re honoring and have consciously elected to continue doing so.

Another benefit of such studies is they deceive the public by presenting something clear-cut – the glorification of Nazi slavers – as a nuanced issue worthy of discussion. This creates the false premise there are multiple angles to the story; in other words, the studies allow for the “both siding” of Nazis.

The inherent absurdity can be striking. Last February, the Krupp foundation – named for a Nazi convicted of crimes against humanity at Nuremberg – unveiled the beginning of a study exploring Krupp’s “relationship toward National Socialism.” Imagine an organization named for Osama bin Laden, another deceased multi-millionaire with a penchant for mass murder, hiring historians to examine bin Laden’s relationship toward Islamic terrorism.

Or take BMW Foundation Herbert Quandt, whose namesake ran a battery company that forced concentration camp inmates to work in such barbaric conditions it killed an average of 80 slaves a month.

The history section of the foundation’s site contains information about Quandt’s past referencing a report that was done into his personal history. According to the foundation’s summary of the findings, “Many forced laborers fell ill and did not survive these cruel conditions. As personnel manager, Herbert Quandt, who joined the NSDAP [Nazi Party] in 1940, was aware of the conditions in the factories.” Yet the foundation’s mission statement is to promote “responsible leadership.”

Reporting on Nazi-named foundations invariably leads to the question of what next. Isn’t it good that money, much of it made off of war crimes, is being put to benevolent purposes?

This is another example of obfuscation, which enables the whitewashing of Nazis. It’s predicated upon a false choice: either you let them build charities, schools and streets named after Third Reich figures, or they’ll take their money elsewhere.

No such choice exists. Several of the foundations in question are large entities tied to businesses. They’re a part of society and can be influenced just like any other corporation.

Indeed, there are examples, both in Europe and the US, of public pushback preventing the glorification of slavers without ending the funding. This was the case with Frankfurt’s Goethe University in 2019, when student and faculty protests led to the renaming of a campus lounge that honored a Nazi Party member who used slave labor.

Otherwise, insisting we must acquiesce to honoring Nazis – lest the charities withhold their money – is tantamount to letting them hold their victims hostage in death as they imprisoned their bodies in life.

Today’s resurgence of global White supremacy has brought us horrific images of far-right groups in Eastern Europe holding marches to honor local Holocaust perpetrators.

Germany’s approach is less vulgar yet exponentially more hypocritical. It takes schoolchildren on concentration camp visits and to history museums. It lectures other nations about Holocaust denial. It goes out of its way to sentence a 97-year-old former Nazi secretary.

And it does all this while some of its elite institutions, universities and municipalities thrive on Nazi money in exchange for rehabilitating the images of prominent Third Reich slavers.