On Nov. 23, USA Today published an article detailing six universities’ refusal or lack of compliance when asked for Title IX data. Among those universities, Auburn topped the list.

Auburn was included in the article because the University denied several of USA Today reporter Kenny Jacoby's requests to see Title IX data between April 2021 and October 2022. In the article, Jacoby described his interactions with University officials.

In April 2021, Jacoby reached out to former Assistant Vice President for Communications Mike Clardy to no response. Jacoby then filed an open records request; however, he was told no records existed containing the data he hoped to see. He then emailed Clardy again. Clardy responded by asking if he had received a response from the Open Records Office.

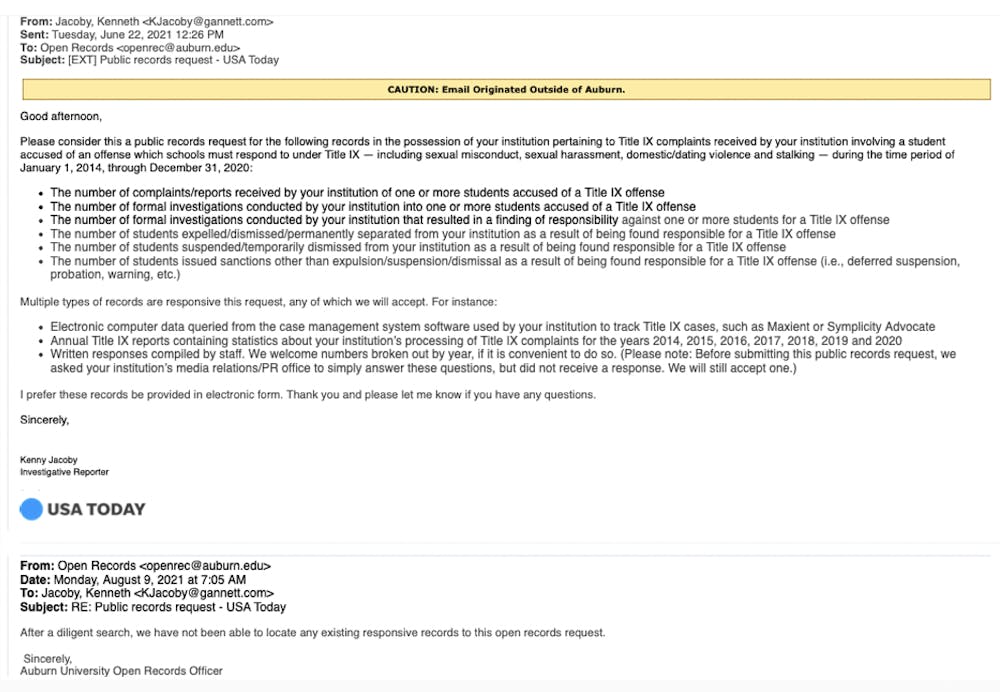

After receiving no response from a second open records request, Jacoby was eventually told in October 2022 after filing a third open records request that the office was declining to provide any data to him “pursuant to the University’s discretion under FERPA.”

The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act is a federal law that protects the education records of students. Executive Director of Public Affairs Jennifer Adams told The Plainsman that “the reporter requested specific student names and discipline records, which by law and University policy we could not release.”

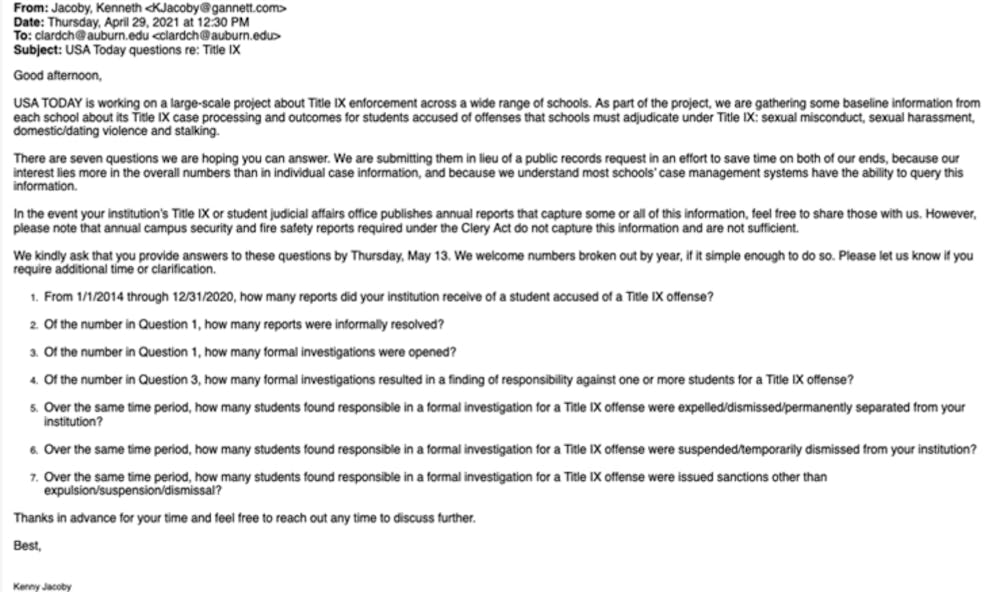

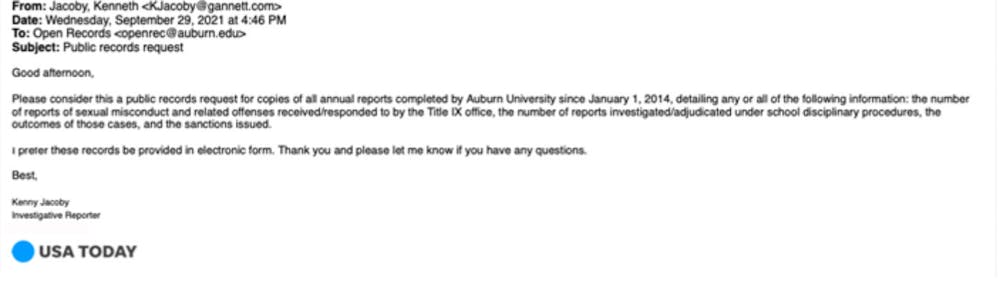

However, Jacoby also provided The Plainsman with several email exchanges he had with university officials. These emails included his line of questioning:

These emails contain Jacoby’s request for Title IX information between January 2014 and December 2020, including data regarding the number of informal resolutions, the number of formal resolutions, how many cases ended in finding a respondent responsible and information detailing suspensions and expulsions. Open Records’ response to the email simply said they were unable to find records responsive to Jacoby’s request.

When asked what specifically under FERPA Jacoby’s request could violate, the University pointed to an earlier email exchange from 2019 in which Jacoby had requested more specific information, including names and specific sanctions.

Jacoby provided The Plainsman with this 2019 email exchange and said it was for an unrelated story to their November 2022 story; however, due to its length, the correspondence could not be published as an image.

This email to Open Records requests the names of students who allegedly committed a crime of violence or a nonforcible sex offense, the violation committed and the sanctions these students received. Jacoby then refers to the Department of Education’s guidelines which allows for this information to be released under 34 CFR §§ 99.31(a)(14).

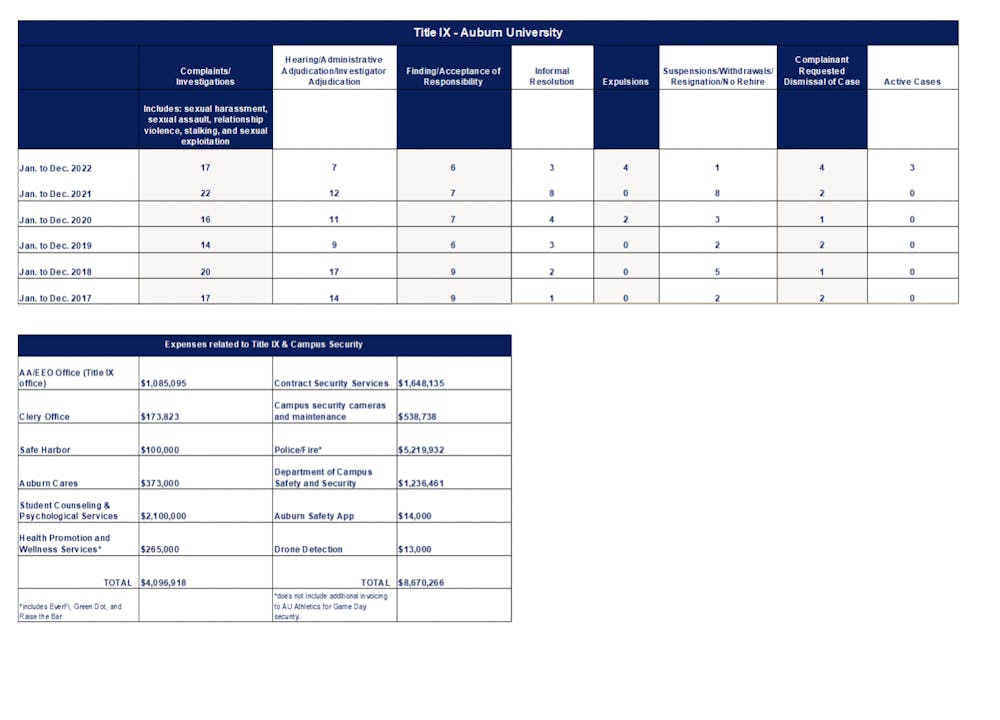

In the University’s response regarding their grounds for denying Jacoby Title IX data in 2019, 2021 and 2022, Executive Director for Public Affairs Jennifer Adams said that while they were able to release the names of students who allegedly perpetrated violent crimes, most universities choose not to release them. Adams also provided The Plainsman with this graphic containing Title IX data:

The graphic breaks down information collected by the office since 2017. It contains data regarding the number of complaints, investigations, findings of responsibility, informal resolutions, specific sanctions, requests for a dismissal and active cases. The graphic also shows the funding that the Title IX office received for fiscal year 2022.

Deputy Title IX Coordinator Katherine Weathers also said that 95% of cases are student-on-student and 95% of complaints are filed by females.

Title IX Coordinator Kelley Taylor said that Jacoby had requested data that the office could no longer provide due to a change in the office’s database. Taylor said the process would have been very time consuming and that Jacoby never specified that he would accept data from a shorter time period.

In Jacoby’s second open records request (shown above), he did not say he was willing to accept data outside of the specified time period he requested, as Taylor had said.

Weathers said that the office was not even required to keep records for as long of a period as Jacoby sought. She said that seven years was standard for keeping and maintaining records.

“Auburn is not hiding data,” Weathers said. “We’re proud of the work we do. There’s not an issue around being afraid to share data because we know what we do is the right thing, and we’re working hard to help people who are victims of these types of incidents.”

The Role of the Title IX Office and How It Functions

Both Taylor and Weathers noted that the distrust of their office by the University's population is their fault and something they hope to change. They hoped to do so by letting students and others know what their office did and how they did it.

While their office does work on civil rights issues of all kinds, Taylor said that approximately 75% of their work is directed toward Title IX-related issues.

According to the U.S. Department of Education, Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 states that “no person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”

Weathers said the office’s areas of focus under Title IX policy is sexual harassment, sexual assault, sexual exploitation, intimate partner violence and stalking. The office fields reports of these actions and “has an obligation to respond to them."

“We have an office of professionals who have a lot of experience, who work very hard and are dedicated to helping the community feel safe,” Weathers said. “And it bothers us just as much as anybody to hear that people may not have that same feeling.”

Taylor said that in order for the investigative process to begin, a report must be sent in either by the complainant or by faculty and staff, or as Taylor called them, “mandatory reporters.” She also said that most complaints do not come directly from the complainant; they most often come from Campus Safety and other sources.

Following the initial report, the Title IX office either speaks with the complainant over the phone or in-person, or they reach out via email to them offering supportive measures “like no contact directives or academic assistance.” They also offer their services in this correspondence if the complainant desires to go forward into an investigation.

According to Weathers, their email outreach, which is eventually sent to all potential complainants, receives a response approximately 25% of the time. The office then explains the possibilities going forward, offering assistance in several ways or launching the process to hold the accused accountable. Weathers then said that of the 25% that respond, approximately 10-11% express interest in going forward with an investigation.

“Would we like to see that number go up? Yes,” Weathers said. “We would love to see more people come forward and say ‘yes, I want to move forward and hold this person accountable.’”

Auburn’s Title IX office has two policies in place: one takes care of any on-campus offenses and the other deals with sexual assault off-campus. This is because if any offense that falls under Title IX takes place off-campus, the University has no obligation to field the complaint. Weathers said that Auburn chose to adopt the two policies so that they can hold more people accountable for wrongdoing.

In these guidelines, the office is tasked with sending a Notice of Investigation to both parties involved, the complainant and respondent. Weathers said that this essentially charges the respondent. The email contains a two-page letter detailing as much information as possible about the alleged instance.

The letter lays out where, when and how a Title IX policy was violated. Weathers noted that it is common for multiple violations to have occurred. Following this information, support resources are listed for the complainant and the investigating officers are divulged.

Also in this letter, both parties are allowed to request an informal resolution. Whichever party is interested in the process is asked to sign a document expressing their desire to informally resolve the issue, and the other party is then notified of this by email. A form is attached to the email if the other party is interested in this resolution process.

If both parties agree to this process, they tell Weathers what they believe is a proper resolution, and Taylor is required to provide what she believes would be a fair resolution.

“It has to be agreeable to all three parties,” Taylor said. “Once it’s agreeable to all three parties, it’s memorialized on paper, sent to the first party for a signature, returned, sent to the second party for a signature, returned, sent to the third party for a signature and then everybody gets a copy, and it closes the case.”

During this process, either party is allowed to request a return to a formal investigation. However, they can return to an informal resolution request throughout the formal process after they see what the evidence is showing and what the witnesses have said. The informal resolution process is available to either party to request at any time.

Weathers explained how once a respondent sees where the evidence is going, they can request the informal resolution to avoid the possibility of a harsher sanction than the complainant may desire.

If an official investigation is launched and is taken through the formal channel, the complainant is contacted by the investigators first. In this meeting, complainants provide their account of the incident and are asked to provide any evidence they may have regarding the situation and any possible witnesses to the event.

The respondent is then contacted and asked similar questions. The evidence, including any interviews and witness statements, is gathered into a report for both parties to review

“At this time, they get to see what the other party said occurred, they get to see what the witnesses said,” Weathers said. “There’s a No Retaliation clause in our policy, so we tell witnesses that if somebody does retaliate against them for participating, they need to let us know, and they will be held accountable for that.”

Weathers said that any party trying to harass or intimidate the other party involved will be held accountable as well. This means that if a complainant or respondent tries to intimidate the other party into not going forward as they desire, the intimidating party will be held accountable for this breach of policy.

As the evidence is laid out before each party, they are allowed to comment on it. Comments may include notes of irrelevance, in which case an investigator is notified before compiling the information into a final report.

The adjudication hearing process follows. These meetings are conducted over Zoom to keep the parties separate from one another.

In order for a party to be found responsible, Taylor said that the evidence had to show it being “more likely than not” that they violated a policy.

One party just needs a slight edge over the other to be exonerated. Weathers compared it to a touchdown being called once the offense has crossed the 51-yard line. Taylor noted that the amount of evidence required by their office is much less than a court of law.

A decision is not made by the Title IX office regarding whether a party is at fault; their office can be more accurately described as a facilitator to the process, ensuring that federal Title IX regulations are met throughout the investigation.

The decision is made by an external hearing officer. This officer reviews the official evidence reports compiled by Title IX investigators and determines whether there is a preponderance of evidence against the respondent or not.

“It’s a facilitation process,” Taylor said. “We’re not decision makers.”

Once the hearing officer reveals their findings, both parties have an opportunity to appeal the decision. If the respondent is found responsible, sanctions determined by the hearing officer are taken against them.

Do you like this story? The Plainsman doesn't accept money from tuition or student fees, and we don't charge a subscription fee. But you can donate to support The Plainsman.

Tucker Massey, junior in journalism, is the content editor for The Auburn Plainsman.