Good morning. Two days ago, the Observer reported a story that seemed to set a new low for the authorities’ handling of asylum seekers who come to the UK by small boats: dozens of vulnerable children, with no parent in the country, being abducted from outside Home Office-run hotels and disappearing. And yet that summary only scratches the surface of the policy mess that has left them so at risk.

At one hotel alone, 79 children are still unaccounted for. In many cases, they may have been picked up by criminal gangs, perhaps having been told that they will be sent to Rwanda if they stay. And yet there is no timeline in places for ending the practice of putting children up in hotels, a temporary policy created to deal with an emergency that has become the norm.

Yesterday, a government minister admitted that 200 children are missing from six Home Office hotels. But he could not put a date on when the practice would end. In today’s newsletter, Laura Durán, of the rights organisation Every Child Protected Against Trafficking (Ecpat), explains the stopgap solutions that led to a shocking threat to children’s safety – and why there is little sign of the problem being solved. Here are the headlines.

Five big stories

UK politics | Rishi Sunak has instructed his ethics adviser to investigate the tax affairs of the Conservative party chair, Nadhim Zahawi, but faces growing pressure over whether he knew about an HMRC inquiry when he appointed Zahawi. The prime minister admitted there were “questions that need answering” over Zahawi’s affairs.

Probation | Ministers and the probation service have been accused of having “blood on their hands” after a watchdog uncovered failings which left Jordan McSweeney free to murder the law graduate Zara Aleena. A report said McSweeney should have been identified as a high-risk offender with a long history of misogynist and racially-aggravated incidents.

Media | Richard Sharp’s selection as BBC chair is the subject of two separate investigations, it was announced yesterday, amid allegations he helped Boris Johnson secure a loan of up to £800,000 weeks before he was recommended for the job by the then prime minister.

US news | Seven people have been killed in two shootings in an agricultural region of northern California, authorities said on Monday. The news follows the killing of 11 people over the weekend at a ballroom dance hall in the south of the state.

Education | A four-year-old British boy called Teddy Hobbs has become the youngest member of Mensa after he taught himself to read and count – including in Mandarin – while playing on his tablet.

In depth: ‘We had a warning from day one that this was absolutely going to happen’

In August 2020, Kent county council announced that it was doing the “unthinkable”: declaring that it could no longer look after unaccompanied child refugees. After caring for more than 1,500 such children since 2014, the local authority said the system was under “impossible strain”. “The stark reality,” said council leader Roger Gough, “is that … the council simply cannot safely accommodate any more new arrivals at this time.”

If the situation was unthinkable, it was nonetheless allowed to persist. The government made an existing voluntary national transfer scheme mandatory, but Kent said that this had not been enough to solve the problem. In June 2021, the council said its services had again reached “breaking point”.

The council said it had double the number of children in care that it could safely handle, and warned that it would seek a judicial review of the Home Office policy. A month later, an emergency alternative was put in place: housing the children in hotels.

To understand the gravity of Mark Townsend’s report for the Observer on children being kidnapped from these hotels, you first have to understand how predictable it was. “It is shocking, but it is not surprising to us,” said Ecpat’s head of policy Laura Durán. “We have been warning the government from day one that this was absolutely going to happen.”

What protections are in place for unaccompanied child asylum seekers?

In theory, children who arrive in the UK by small boats are “entitled to the same local authority support as any other looked-after child”, the Home Office’s 2017 safeguarding strategy (pdf) said. That is not the reality for the children who have found themselves in hotels, where they typically stay for about two weeks.

“When this started, the position was that it was an emergency – and the Home Office had absolutely no authority or legal basis for accommodating children,” said Durán. “It amounted to them excluding a whole group of children from the UK’s child protection framework because of their immigration status. And now the emergency has been carrying on for almost two years.”

By rights, these children should have a care plan, access to education, proper medical care and a host of other entitlements. But a report (pdf) by the Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration (ICIBI) on four hotels last year found that while children felt safe and happy, they had “perfunctory” English lessons with no formal schooling, no access to legal advice or prescriptions, and in all but one hotel no fully functioning kitchen. They were being looked after at two of the hotels by staff who lived on site with access to master keys but had not been vetted through the Disclosure and Barring Service.

Perhaps most urgent is the question of what happens if they go missing. “If that happens, there are really specific steps that are supposed to be taken,” said Durán. “You have to hold a meeting, determine the risk, that determines the level of investigation that will be carried out and how information is shared – a host of things. But in these hotels, nobody is taking that responsibility.”

In October, ministers admitted that of 222 vulnerable children whose whereabouts it did not know at the time, 39 had been gone for more than 100 days. Now Mark reports that dozens of children have been effectively abducted from one Brighton hotel alone, in a pattern apparently being repeated across the south coast.

Can anyone stop this?

The police’s policy on how how to respond when asylum-seeking children go missing is still in “development”. In the meantime, “Children are literally being picked up from outside the building, disappearing and not being found,” a child protection source said.

When staff and security guards see this happening, there is astonishingly little they can do. “We can’t run around the area, checking to see who’s where,” a whistleblower working for outsourcing firm Mitie said. “We can’t arrest the children, we can’t detain them.”

“The hotel staff are independent contractors,” Durán said. “Ultimately all they can do is ring the police.” Even that limited redress only works if they see the incident in the first place. While the police has warned the Home Office that the children would be targeted by criminal networks, it says it has received no kidnapping allegations.

What do we know about the children who go missing?

The children staying in the hotels are teenagers: government figures released in October said that almost 900 14- and 15-year-olds, and more than 2,000 16-and 17-year-olds, had been housed in hotels since October 2021. Home Office minister Simon Murray told the House of Lords yesterday that of 200 currently missing, all but one were boys, and 13 were under 16.

The Home Office denies that any children have been abducted; on the other hand, Murray said it would be wrong to “make generalisations” about why they are missing. In some cases they will be choosing to leave with family and friends, but that still leaves vulnerable children outside of the safeguarding system, Durán said – and there is evidence that some are in much bleaker circumstances.

“There’s no clear way to know how many are being trafficked or exploited,” she said. “But we do know that these children don’t have a parent here, may come from a background of war in their home country, may be escaping from a situation of domestic abuse.”

The Mitie contractor told Mark that “most of the children disappear into county lines” – the criminal enterprise of transporting drugs out of cities to towns and rural areas. “The Albanian and Eritrean gangs pick them up in their BMWs and Audis and then they just vanish.” 176 of the currently missing children are of Albanian origin, Murray said. One hotel in Hove is a known hotspot for exploitation, with gang members congregating a few hundred metres away.

Why is nothing changing?

As the Home Office’s emergency plan has morphed into the status quo, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that often-repeated inaccurate claims that many are simply adults pretending to be younger has shaped the urgency of the response. The ICIBI report said that Home Office staff viewed children as “flight risks” who might “abscond”.

“That rhetoric has created a huge culture of disbelief, not just in the Home Office, but in law enforcement as well,” Durán said. “And it can have an impact on the police response – it can be assumed that they are deliberately disengaging because they are avoiding immigration enforcement.” In reality, none of the children staying in these hotels have been found to be older than they claim.

The Home Office has refused to accept an urgent timeline to meet the ICIBI report’s recommendations. Meanwhile, it is particularly striking that, when asked for comment, Brighton and Hove council referred questions to the police; the police passed them on to the Home Office; and the Home Office said the council was responsible.

after newsletter promotion

“There is a game of pass the parcel,” Durán said. “Nobody wants to be blamed. But at the end of the day, the ones paying the price are these really vulnerable children.”

What else we’ve been reading

The Guardian’s former Middle East editor Ian Black (pictured above), who has died aged 69, has been remembered by his colleagues as “endlessly curious, wise, even-handed and knowledgable”, “funny, engaging, and an elegant writer”, and “just a lovely man”. This short 1982 piece about the Lebanon war is testament to his prodigious gifts, and his last piece, co-authored with his wife Helen Harris, is as powerful as anything he ever wrote. Archie

For Cathy Reay, a routine sexual health checkup became a demeaning and difficult experience due to accessibility barriers. Reay lays out how sexual healthcare does not serve disabled people and why this has to change. Nimo

For a sense of the Conservatives’ uneasy mood on the future of Nadhim Zahawi, see this piece on ConservativeHome by Paul Goodman. “Some will take the view that someone’s tax bill is their own private business,” he writes. “This is hard to maintain when the person concerned is chancellor of the exchequer.” Archie

The dizzying array of options on supermarket shelves give the false sense that we have more food choices than ever. Clare Finney dives into how this misconception of diversity in food options have led to food shortages, health problems and have fuelled the homogenisation of our palates. Nimo

Sam Levin interviewed three people who are speaking about the abuses they faced as minors while imprisoned in America’s largest juvenile system, as almost 300 people come forward in a lawsuit against LA county. Nimo

Sport

Boxing | After a bout between influencers KSI and Faze Temperrr (above) attracted 300,000 pay-per-view buys last weekend, Jonathan Liew writes the “really interesting part” about this “curious parallel universe”is why the level of interest is so high “in a product that – by any objective sporting standard – is not very good”. The question for boxing, he adds, is why it is “so ripe for parody”.

Premier league | Everton have sacked manager Frank Lampard after a disastrous run of 11 losses in 14 matches. Marcelo Bielsa and Sean Dyche are reported to be among the possible successors. Barney Ronay writes that while Lampard’s firing is justified, “The real problem is simply that [Everton chairman Farhad] Moshiri and his board are extremely bad at running a football club.”

Premier league | Tottenham Hotspur beat Fulham 1-0 thanks to a Harry Kane goal that equalled the club’s all-time scoring record. The victory puts them three points below fourth-placed Manchester United.

The front pages

The Guardian print edition leads today with “PM admits ‘questions need answering’ on Zahawi tax”, while the Daily Mirror says “Tories still don’t get it … the only way is ethics”. The i has “Zahawi faces sack as PM demands answers on Tory chair’s unpaid taxes”, going toe-to-toe with the Financial Times for word count: “Zahawi fights for political life over tax scandal as Sunak orders ethics review”. “Rishi: dish the dirt” – that’s the Metro on Sunak ordering an inquiry into the Zahawi affair.

Boris Johnson writes for the Daily Mail today and takes over the front page to ask, about Ukraine: “What the hell is the west waiting for?”. “Asylum cheat sneaked into UK to kill for third time” – that’s the Express, and the Telegraph has the same lead: “Killer posed as a child to claim asylum and murder again in UK”. The lead story in today’s Times of London is “Met ‘risks hiring rogue officers’ in online tests’.

Today in Focus

Why is Scotland’s gender reform bill so contentious?

The bill was supposed to streamline the way that people can apply to change their legal gender. So why has it sparked a constitutional crisis – and become a culture war battleground?

Cartoon of the day | Martin Rowson

The Upside

A bit of good news to remind you that the world’s not all bad

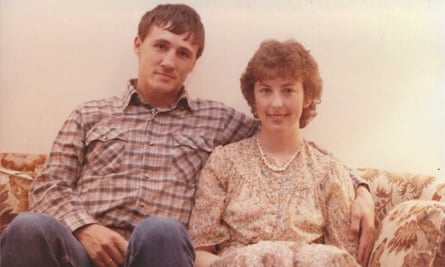

In the early 1980s, John decided to move from Iowa, in the US, to Saudi Arabia to be a field engineer for an electrical firm due to economic hardship in his home state. It was steady work, but there was very little to do in his spare time – until his colleague, Robert, introduced John to his sister-in-law who lived in Yorkshire via letters. A friendship bloomed and within a year they had made plans to meet in London. Over time, the pen pals realised there was a romantic spark and, after spending a month in the UK with Jane, John decided to pop the question.

By 1986 they were married and had a daughter on the way. They spent the next decade and a half travelling from Saudi Arabia to Kuala Lumpur, back to England, and eventually settling in Wisconsin in 1999. Through loss, sickness and immense change, the two developed an unshakeable bond that came from just a few letters. “All these years later, we still really like each other,” said Jane. “We can argue and then just forget about it. We’re best friends.”

Sign up here for a weekly roundup of The Upside, sent to you every Sunday

Bored at work?

And finally, the Guardian’s crosswords are here to keep you entertained throughout the day – with plenty more on the Guardian’s Puzzles app for iOS and Android. Until tomorrow.