The big screen counterparts to Ian Fleming’s James Bond novels are not always the most faithful of adaptations. In fact, most have only a flimsy connection to their namesake. Diamonds Are Forever and The Man with the Golden Gun, for example, have only a vague resemblance to their source material, taking the character names and general feel of these books and then placing them in a largely different narrative. This wasn’t always the case - On Her Majesty's Secret Service made only minimal changes, for example – but it was definitely the norm, making for some odd experiences if you’re more familiar with the books. Hardcore fans have been clamoring for the films to stick closer to Fleming’s originals for decades. While the debate over whether these changes were ultimately for the best shows no sign of slowing down, there is one example where it’s hard to argue that the version moviegoers got was anything but a downgrade – Moonraker.

A Bond Film That More Resembles 'Austin Powers'

It’s been 43 years since Roger Moore’s 007 strapped himself into a rocket and jettisoned into outer space to stop a modern-day Noah’s Ark from wiping out Earth’s population with toxin derived from a particularly nasty orchid, and none of the ensuing time has helped mitigate how utterly stupid all of that sounds. Moonraker’s reputation as the franchise’s lowest point is well documented, and in the years since, it has become the template all future entries have tried to avoid. What was once a series of realistic spy thrillers that examined the current socio-political climate through the vector of entertaining stories was gone, replaced by a comedic farce that resembled Austin Powers eighteen years before that was even a thing. This isn’t to say that the James Bond films have always been exercises in realism – let’s not forget that this is the franchise that has a character called Pussy Galore – but there was a plausibility to his earlier adventures that later entries had chipped away at, with Moonraker serving as the apex of this trend.

This misguided approach makes Moonraker a painful enough watch by its own merits, but when combined with the knowledge that it’s the anthesis of what Fleming was trying to do with his original novel, this pain grows even worse. It was released in 1955, hot off the success of Casino Royale and Live and Let Die which had propelled a Second World War naval officer into becoming one of the world’s most famous writers. However, anything that garners praise from both critics and audiences is guaranteed to draw detractors, and Bond was no exception. Criticisms that the books were just light entertainment that failed to portray an accurate depiction of intelligence warfare were not uncommon, and the increasing popularity of the series only spurred on these sentiments. But Fleming was never one to back away from a fight, and when it came time to bunker down in his Goldeneye estate and turn out another 007 adventure, he was determined to prove his detractors wrong.

The 'Moonraker' Novel Relefected 1950s Britain

Moonraker was his answer to these criticisms. While the premise still adhered to the basic framework fans had come to expect (Bond has to stop a cartoonishly evil villain from achieving global domination with the help of his latest girl-of-the-week), Fleming used this as a basis to explore contentious political issues that were highly relevant to a 1950s audience. This was a time of much dread, with memories of the Second World War and the first use of an atomic weapon still fresh in everyone’s mind. Fears of a new global conflict escalated by the day, prompted by a bitter arms race between the United States and the Soviet Union as they fought to become the dominant superpower. It was amidst this backdrop that Britain found itself forced to re-evaluate its place on the world’s stage, the gradual loss of its territory and a diminishing influence on international affairs making the nation that had once commanded the largest Empire in history seem more and more like a footnote.

Hugo Drax Is The Most Realistic Bond Villain

It’s within this changing world that Fleming introduces us to Hugo Drax, an amnesiac veteran of WWII who has transformed himself into the most famous multi-millionaire industrialist in Britain. His crowning achievement is the titular Moonraker project, a long-range nuclear missile capable of reaching any target in Europe. If successful, it will guarantee Britain’s safety in the turbulent days ahead, a prospect that has caused the entire population to herald him as their savior. All except M, that is, and when he calls Bond into his office for the usual pre-mission briefing, he’s happy to make those concerns known. Good thing too, since the Moonraker project is only five days away from being tested and its chief security officer has just been shot dead. Bond is assigned as his replacement, and soon after, finds himself following the trail left by his deceased predecessor as he seeks to uncover what’s really going on, aided by an uncovered operative called Gala Brand who has been posing as Drax’s assistant.

It shouldn’t be a spoiler to say that Drax isn’t being fully honest about his intentions – turns out he’s a former Nazi who plans to use Moonraker to destroy London, and is ultimately killed by his own creation after Bond reprograms its flight trajectory – but it’s hard to imagine that Fleming was trying to create a thematically complex character that would see him unleashing his inner John Steinbeck anyway. Not that any of this stops him from being engrossing. He doesn’t have the recognizable look or signature weapon of other Fleming creations, but what he lacks in cheap theatrics he makes up for with sheer intelligence, resulting in one of the most credible villains in the series. When Bond is explaining his backstory during the initial briefing with M, we’re told that Drax is the classic rags-to-riches story, transforming himself from a lowly worker on the Liverpool docks to a powerful businessman who decides the fate of Europe over his morning coffee. By all accounts, he’s a positively English gentleman, sporting a suave and pleasing demeanor that sees him ingratiated into the upper echelons of high society – an assessment that holds true when Bond’s first encounter with him comes over a game of bridge in one of London’s most prestigious clubs.

Using Britain's Paranoia Against Them

But this persona is a lie, a ruse designed to trick a frightened nation into signing its own death certificate just because a well-dressed man with a received pronunciation accent dangled the carrot of turning their greatest fear (nuclear warfare) into the tool that would regain them their place as the world’s most powerful state. Given how much terror stalked the streets of Britain at this time, it’s not unbelievable that someone would be able to bewitch an entire population just by playing to their sense of national identity. It’s also not unbelievable that when cracks start to appear in his story, there’s a strident effort to explain them away as misunderstandings. Even Bond falls victim to this mindset, trying to convince himself that the security officer’s murder was unrelated to Drax well into the novel’s second half. By playing into fears that were dominating the thoughts of a 1950s audience (such as the resurgence of Nazism and the potential threat to the British way of life), Drax becomes the perfect antagonist for this specific country during this specific period of its history.

'Moonraker' Explores Britishness More Than Any Other Bond Novel

This exploration of Britishness is the most defining aspect of Moonraker and becomes the foundation from which everything else is built. Despite the 007 franchise being one of Britain’s most famous creative exports, very little of the series takes place in Bond’s home country. This is hardly shocking given his role as an MI6 agent, but it does mean that there are limits to how Fleming can address Britishness and how the meaning of that term evolves through the years. In this regard, Moonraker takes the opposite approach. It’s the only Bond novel set entirely in Britain, a fact Fleming is clearly relishing given how the sequences in London feel akin to a sightseeing tour of the capital’s most famous landmarks. It borders on overpowering, but it succeeds in highlighting the virtues of England that Drax threatens to destroy. It’s no coincidence that the location of the Moonraker test site is above the White Cliffs of Dover, a symbolic guard against Britain’s enemies that has stood undefeated for almost a thousand years. It’s not a subtle piece of imagery, but as a means of conveying an idea that would haunt any of the novel’s intended readers, it’s hard to think of something more effective.

Differences Between the 'Moonraker' Novel and Movie

Those not familiar with the Moonraker novel may be confused about how different all of this sounds from its cinematic counterpart, but as previously established, that’s par for the course with this series. Famously, it was not supposed to be the follow-up to 1977’s The Spy Who Loved Me (an honor that was supposed to go to For Your Eyes Only) but was rushed into production after the overnight success of Star Wars. The result is a film that is effectively unrelated to the novel it claims to be based on, with integral elements of the original being cast aside like they were nothing (forget a story that never leaves England, this one can’t get away fast enough). To some extent, this is understandable. Despite the potential ramifications of Drax’s plan, the actual Moonraker novel is presented in a very small-scale way, focusing on lengthy dialogue sequences in just a few locations without much action to break things up. Audiences would never have accepted a faithful adaptation given what the previous films had established the series to be, but that wouldn’t have made it impossible to still retain the spirit of what Fleming was trying to achieve with the book.

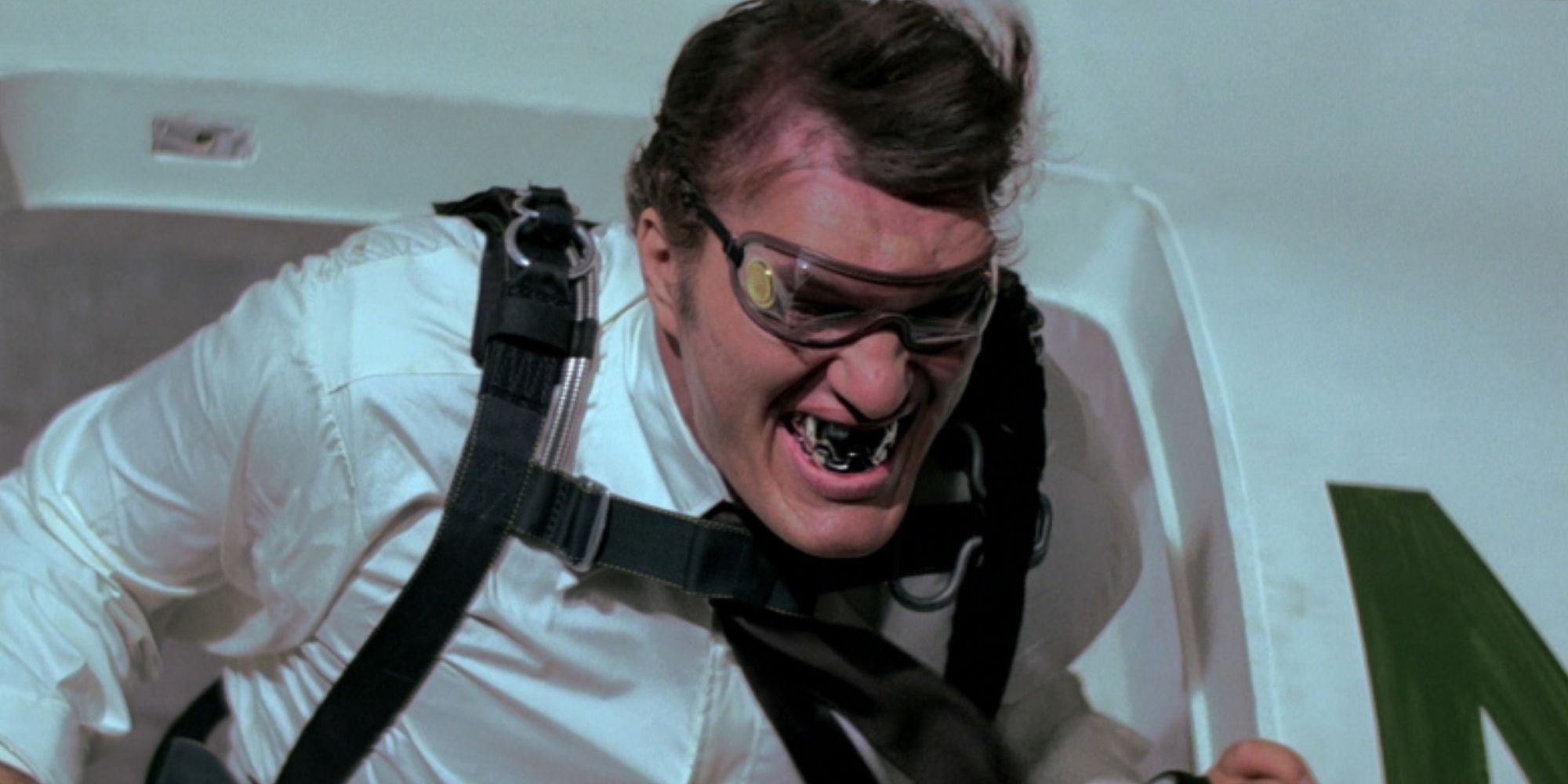

Seemingly, director Lewis Gilbert disagreed. From the moment we witness a character with steel for teeth survive a fall of several thousand feet by landing on a circus’s trapeze net, it’s clear that what used to be Bond’s most serious adventure is now his most outlandish. The next two hours continue this trajectory, never failing to find time for absurd set pieces like Bond driving around Venice on a hovercraft gondola or fighting a comedically fake python while surrounded by a group of women who look like they’ve just walked off a Vogue fashion shoot. And then there’s the outer space element, a sequence so ludicrous in both conception and execution that it manages to make an army of astronauts firing lasers at each other uninteresting. Some defend Moonraker as a piece of fun turn-your-brain-off cheese, but Gilbert’s direction is too dry and Michael Lonsdale’s depiction of Drax is too boring for that to work. It feels afraid to fully commit to its style, and still includes the occasional moment that feels better suited in the other, more grounded entries (a scene where a supporting character is torn apart by dogs springs to mind). In short, it’s a mess, and it’s no surprise that For Your Eyes Only did everything it could to return to the feel of the earlier films.

But, It All Worked Out.. I Guess?

And yet, it still succeeded. Moonraker became the highest-grossing entry in the series, a record that remained unbeaten until 1995’s Goldeneye. The gamble at making the 007 equivalent to Star Wars paid off, meaning any efforts to brush it under the rug would be impossible. Weirdly, this does see it adhering to the concept that Fleming had constructed his original novel around – that Moonraker, more than anything else in the series, reflects the era in which it was made. Of course, crafting a personal story about nuclear annihilation and what it means to be British in an increasingly modernizing world is very different from Hollywood producers chasing the prevailing winds of box office hits, but there is some connective tissue there. It’s unlikely this is what Gilbert had in mind, but it’s interesting to consider.