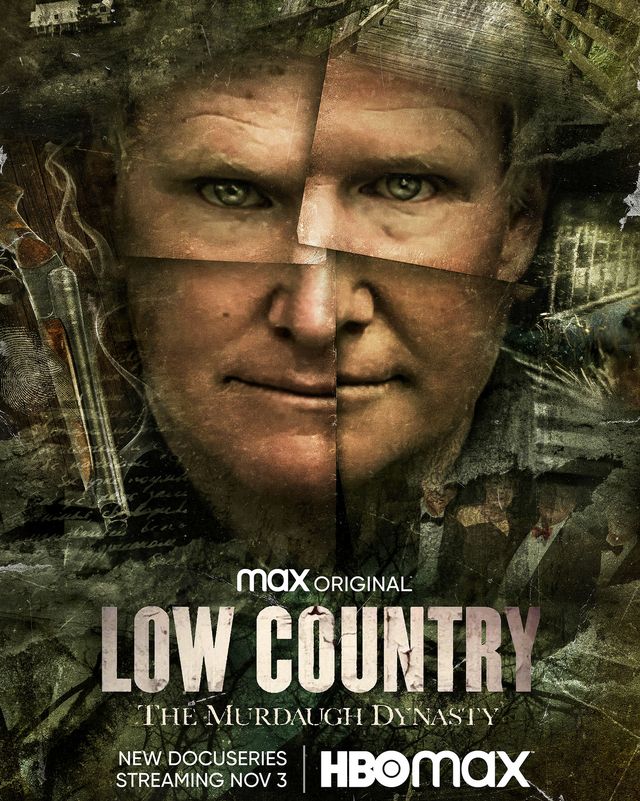

Earlier today, a federal judge sentenced Alex Murdaugh to 40 years in prison after he was found guilty of stealing money from his law firm and numerous individual clients. In March 2023, Murdaugh was convicted in a South Carolina court of murdering his wife and son and sentenced to life in prison without parole. He will serve both sentences concurrently. Prosecutors in the federal case asked for a sentence of up to 22 years, but the U.S. district judge opted for longer, he said, because Murdaugh swindled particularly vulnerable—in some cases desperate—victims out of their life savings. In light of today’s sentencing, we're resurfacing Mark Seal's reporting on Alex Murdaugh and the deaths of his wife and son Paul from the December 2022/January 2023 issue of Town & Country.

The bodies begin dropping in the summer of 2015. Stephen Smith, 19, found dead in the middle of a road in Hampton County, South Carolina, on July 8. Smith is gay, and his mother believes her son was killed in a hate crime, a newspaper will report, “by several local Hampton County youths from prestigious families.”

In 2018 Gloria Satterfield, a long-serving housekeeper for a prominent local family, is found dead while at work from “a trip-and-fall accident.” Nothing suspicious, it is called, until the proceeds from her insurance policy go not to her two surviving sons but allegedly to her lawyer.

A year later, in February 2019, a 19-year-old rich kid, drunk at the wheel of his family’s boat, plows into a bridge at 2 a.m. At his side is the beautiful 19-year-old Mallory Beach. She is thrown from the boat and instantly killed.

A name rises from the flotsam of these mysterious yet somehow connected deaths, a name that shocks the South Carolina community where the deaths occur when it is printed in headlines around the globe, bringing the eyes of justice—and the media—to this corner of what is called the Lowcountry.

It is a name that is instantly recognized by the police when, at 10:26 p.m. on June 7, 2021, Sergeant Daniel Greene drives through the stone gates of a 1,700-acre family hunting estate at 4147 Moselle Road, in Colleton County, South Carolina, to find a 52-year-old woman and her 22-year-old son “lying on the ground,” shot dead with a rifle. It is a name oft-heard by the media—never in this context, but on the other side of the law.

The name and the public nature of these two deaths is such an unlikely combination that local law enforcement look back at the deaths of Stephen Smith and Gloria Satterfield and uncover a sinister web of cascading crimes and escalating intrigue. And in the middle of it all, somehow seemingly involved in myriad cases and maybe more to come, is that name, that very famous name, the name that stops investigators and the public dead in their tracks.

Murdaugh Country

Much of the five-county 14th Circuit District of South Carolina is an idyllic coastal paradise of salt marshes and glistening waterways, called “Murdaugh Country” by the locals for the family that has reigned here for nearly 100 years. From 1920 to 2006 the local district attorney’s office was headed by three generations of Murdaughs. They were the law, responsible for prosecuting all state crimes committed within the district’s borders. Like the seawater in their domain, the power of the Murdaughs rippled out in all directions, as the patriarch, Randolph Murdaugh Sr., founded a civil litigation law firm in his hometown of Hampton, South Carolina, in 1910, that would become a powerhouse in the region.

Along with serving as 14th Circuit solicitor starting in 1920, Randolph Murdaugh Sr. also started a local newspaper. He would surely have continued his reign if not for a car accident in 1940, which left him dead at 53. He was succeeded by his son Randolph Murdaugh Jr., who served from 1940 to 1986, Murdaugh power unbroken. But not untarnished: In 1956 Randolph Jr. was indicted by a federal grand jury in a “liquor conspiracy” case: A bootlegger testified that Murdaugh had advised him to move his still into a neighboring county to avoid the police. Soon, though, he was acquitted.

“During the trial, ‘Old Buster,’ while serving as the elected solicitor, was accused of conspiring with bootleggers,” says South Carolina lawyer Joe McCulloch. “He was acquitted but admonished by the federal trial judge for jury tampering. His resounding reelection as solicitor followed within months of the verdict. Of course, he had the inherent advantage of the Murdaughs’ ownership of the prosecutor’s office for decades—all while having a money-machine private law firm. Some have described the seven decades of the Murdaugh reign of power as sovereigns lording over their fiefdom, with literally no adult supervision.”

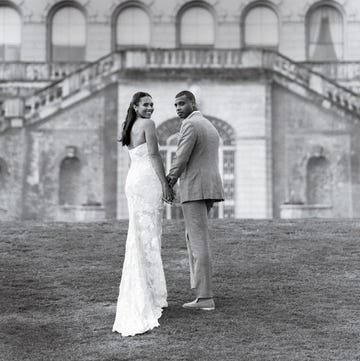

When the family fell, it was, as with everything Murdaugh, huge. On June 8, 2021, news became public of the murders of Margaret and her son Paul Murdaugh at the hunting estate. First, the focus was on not only the two victims but also the living: two of the prominent family’s surviving members, Alex Murdaugh, the husband and father of the victims, and his only remaining son, Buster Murdaugh, 25.

How could Alex and Buster bear to go on after the horrid murders of their beloved Maggie and Paul?

Alex’s brothers, John Marvin Murdaugh and Randolph “Randy” Murdaugh IV, broke their silence on Good Morning America, both of them in tears and revealing that their nephew Paul, who had allegedly been at the helm of the boat in 2019 when Mallory Beach was killed, had been threatened online just days before the double homicide.

Yet as the tale of his wife’s and son’s deaths unfurled in the days, weeks, and months to come, prosecutors would claim that lawyer Alex Murdaugh wasn’t the victim of these horrendous crimes, he was allegedly the perpetrator, at the center of a web of murder, insurance fraud, drug addiction, conspiracy, and coverups—culminating in not only the alleged killing of his own wife and son but also in his allegedly commissioning (or tricking) his distant cousin, client, and alleged drug dealer, Curtis Edward “Fast Eddie” Smith, to kill him. Why? So he could leave Buster the proceeds from his $10 million insurance policy. “It was the craziest situation I ever been involved with,” Smith told the New York Post of the shooting. “I was set up to be the fall guy. And those damn pictures of me in the newspaper! I was looking at them this morning. They didn’t let me take a damn shower!”

“Eddie is shocked, sad, and disheartened by Alex Murdaugh, who continues to try and put him in harm’s way,” says Smith’s attorney, Aimee Zmroczek. “It’s hard to understand the actions of this person he thought he knew; it is even harder to understand the hurtful actions of Alex continuing to use him. It is my goal to protect Eddie from that selfishness, and I will continue to do so until all the evidence is finally presented.” (As well she might. On October 14 Murdaugh’s legal team filed a motion suggesting that Smith should be considered a suspect in Margaret’s and Paul’s murders.)

Other secrets soon came to light, including that Margaret had recently met with a divorce attorney after 27 tumultuous years of marriage, and that her husband was in deep financial trouble with his own law firm and even deeper into a 20-year oxycodone addiction. “It’s fishy,” Margaret texted a friend, according to People magazine. “He’s up to something but I don’t know what.”

But Alex insisted that he had been at his 81-year-old dying father’s bedside just before discovering the bloody bodies on that June evening. He sobbed while calling 911 from the murder scene, “Neither one of ’em is moving… Please hurry!… It’s bad.”

The news kept coming, and then, for almost a year, it stopped. “There hasn’t been one clue about the murders since day one. Nada,” one fact-starved local told me in January, before engaging in a new local pastime: speculation. “Considering all his financial woes, it certainly seems feasible to me that Alex would have hired someone to kill his wife and, I have to think, not knowing that his son would be there. Too much of a coincidence that he was in debt so deeply and maybe about to get busted by his firm for it, and was seeking to buy his way out.”

Then, finally, on July 14, Alex Murdaugh was indicted on two counts of murdering his wife and son. His lawyers released a denial: “Alex wants his family, friends, and everyone to know that he did not have anything to do with the murders of Maggie and Paul. He loved them more than anything in the world.”

“Our position is he’s going to be acquitted,” Alex’s attorney, Richard Harpootlian, told me in October. “We want a speedy trial so he can be acquitted, and law enforcement can go forward in finding the real killer of Maggie and Paul. We anticipate that the truth will come out in his trial. We’re not going to comment on the speculation. I’m focused on preparing for trial so that the jury will hear the facts, not speculation.”

Either way, what happened at the hunting lodge was brutal. Both victims were shot multiple times, one of them with an assault rifle and a shotgun. Brutal enough that it shocked even veteran investigators. “Based on what’s been made public so far, the shooter shot the son in the back as the son was taking a video of his friend’s dog, which he was dogsitting,” says Bobby Chacon, a retired FBI agent turned criminal analyst. “Once this shot rings out, the wife may have started running, and the shooter then transitioned to the other weapon, either slinging the shotgun or placing it on the ground and picking up the rifle, which he then used to shoot the wife. Then he walks over to her and shoots her again.”

“Don’t trust your soul to no backwoods Southern lawyer,” sings country star Reba McEntire in her remake of the 1972 Vicki Lawrence murder ballad “The Night the Lights Went Out in Georgia.” “Reba said it best,” someone posted on the Murdaugh Family Murders Reddit site.

In the beginning, though, the family circled around their grieving brother. “It’s just hard to imagine somebody can be so sick as to do this—intentionally kill people like that,” Randy Murdaugh said through tears on TV. “I mean, we see it in the world. We see it on the news. But you don’t think it’s going to happen in your small community, to your family.”

What the brothers didn’t discuss on Good Morning America—and what they might not have even yet realized—was that the mounting drama surrounding the murders was the result of not merely gunfire but also something hardwired into the American identity, something that unfortunately allows secrets to fester and misdeeds to go unpunished: the archaic notion that in our society certain families are destined to rise to the top.

Rich, successful, powerful, and, from the outside, happy, the “good family” is an ideal that is built up in the eyes of the public, on television and in magazines, like some overblown balloon. And time after time, so often that it has become part of our collective experience, it bursts with a divorce, scandal, financial reversal, or crime, attracting the baying masses, who watch with fiendish relish and wonder, “How?”

“Do You Have a Gun?”

It’s the fall of 2021, and I’m desperately trying to join the pack of reporters who have descended upon Hampton County, in South Carolina, a rowdy state described by Charleston politician James L. Petigru in 1860 as “too small to be a republic but too big to be an insane asylum.” They call us “parachute journalists,” the ones who fall from the sky into heretofore unknown locales for a few days, weeks, or months of reporting, and then depart with the smug sense that we have captured the practically uncapturable.

Journalists from every television network, along with People, the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, and other national publications have flocked to the seat of the Murdaughs, a quiet town called Hampton (population 3,000), mystified, intrigued, and scandalized by the prominent attorney embroiled in all the drama, the latest episode in America’s obsession with true crime.

Ever since Truman Capote took a train to Holcomb, Kansas, in 1959 to chronicle the murders of a farm family for his 1966 true crime novel In Cold Blood, journalists have been flocking to far-flung murder scenes and the front doors of shell-shocked locals. A family name, the bigger the better, is extra incentive. “People think, If I had their money my life would be so good,” says Bobby Chacon. “They forget that money and greed are one of the oldest motivations for violence.”

Close on the heels of the fall of any major family comes the spotlight. “There’s a fantasy that other people have perfect lives,” says Meryl Gordon, author of Mrs. Astor Regrets: The Hidden Betrayals of a Family Beyond Reproach. “We put families on a pedestal, particularly if they have a well-known name or are incredibly wealthy or have achieved great things. There’s a desire, an aspiration to be like them. But usually, if you get closer you discover that they have problems.” Gordon, whose most recent book is about the philanthropist and garden designer Bunny Mellon, says it’s hard to resist the allure. “In writing about famous wealthy families, I have thought, Wouldn’t it be wonderful to have Bunny Mellon money or be Brooke Astor, where everybody wants to know you? If they fall from grace, it’s disappointing, and then comes the realization that they’re just like us and, of course, the schadenfreude.”

For months, from a safe distance, I devoured the lurid headlines. “The Unraveling of the Murdaugh Dynasty: Unsolved Murders, Insurance Fraud and Missing Millions,” Wall Street Journal, September 23, 2021. “Power, Prestige and Privilege: Inside the Rise and Fall of the Murdaugh Dynasty in South Carolina,” Greenville News, January 26, 2022.

But before parachuting into Hampton County (via the Savannah/Hilton Head airport), I made a few calls. “The boating accident was squirrely from the get-go,” said one of the many local followers of the case. “Took unduly long to get around to the actual charges.”

“It’s a Boss Hogg kinda thing,” said retired civil rights attorney Lewis Pitts, who practiced in the Lowcountry, referring to the crooked sheriff of Hazzard County who would do almost anything for money on the ’80s TV series The Dukes of Hazzard.

Finally, I called veteran South Carolina legal affairs reporter John Monk, who suggested half-jokingly that I pack a pistol along with my parachute. “What sort of spell could you weave with your writing?” he asked, adding that I might try to emulate the incredible work of Rachel Kaadzi Ghansah, who won a Pulitzer Prize for her 2017 GQ story “A Most American Terrorist,” about the case of the 2015 Charleston church mass murderer Dylann Roof. “She brought her spell to something that’s been written about a lot. Someone like me, who’s lived here a long time, I know a lot of the players. You could parachute in with a lot of attitude, but unless you spend a lot of time here and really get to know the locals, the story is going to elude you.” He added with a laugh, “And you better hope you don’t get killed.”

I took a breath and asked him what he meant by that, and he laughed again. “In the last few years five people in the Murdaughs’ orbit have died violently,” he said. “Why wouldn’t a word of caution be in order?”

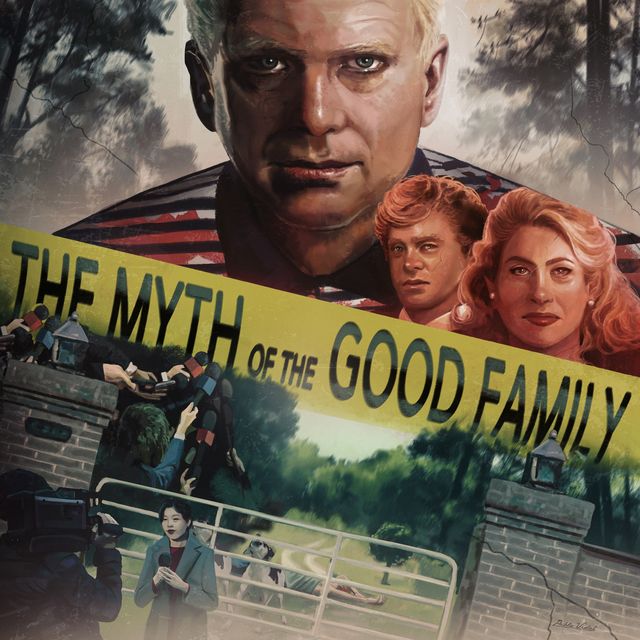

Along with the hellhounds of the media came an even more voracious pack. “The Hollywood production companies and global streaming services, battling for exclusive access and insights,” wrote Will Folks, editor of the South Carolina–based FITSNews service, on September 3, 2021. It had been only three months since Margaret and Paul Murdaugh had been killed, and Folks and his staff had been “inundated with all manner of proposals,” their phones blowing up “with out-of-state area codes,” even while the truth about some of the mysterious events “will forever remain known only to the backroads of rural South Carolina.” He added, “One of the producers pitching me on an ‘advisory deal’ earlier this week sounded as though she were already framing shots. ‘It’s the perfect location,’ she told me. ‘The perfect backdrop.’ ”

To which Folks wrote, “Listen, before we start handing out cinematography awards and selecting the most brooding soundtrack music to accompany all of these cookie-cutter ‘true crime’ productions, I feel obligated to remind the salivating vultures currently circling over Hampton County, South Carolina, that this ‘perfect’ story involves any number of victims who are currently awaiting justice.”

Deals were soon announced. “The true crime story of the Murdaughs, which includes money, power, family drama, corruption, local politics, drugs, and murder, is the subject of a drama series, which is in development at UCP, a division of Universal Studio Group,” Deadline reported on April 27, 2022. The series will be based on the Murdaugh Murders podcast, by local journalist Mandy Matney, which ranked number one globally for 2021, according to the podcast’s marketing page. Having jumped in early, Matney is a frontrunner in the race to “own” the Murdaugh story.

Hovering over it all, of course, are the attorneys. “You can’t toss a dead cat at a bar meeting without hitting a lawyer involved in the Murdaugh case,” says Joe McCulloch, who is representing one of the passengers in the Paul Murdaugh fatal boating accident. “What doesn’t this story have? Mystery, tragedy, crooked lawyers, multiple murders, association with gangs, drugs in spades, and dozens of victims.”

The story has now gone viral, complete with merchandise available online: murdaugh murders T-shirts, coffee cups, and baseball caps. “I heard there’s a guy from the New Yorker, a couple of book authors, Netflix, HBO, Oxygen, 20/20, Dateline,” local writer Jason Ryan, author of the book Jackpot: High Times, High Seas, and the Sting that Launched the War on Drugs, told me in early October. “The revelations have been relentless and dizzying, to the point that the story has outgrown itself to become its own world made up of many smaller, Southern Gothic–type tragedies all tied together by a raft of dead bodies, missing money, and one family’s tremendous fall from grace.”

However, as always, why the Murdaugh family imploded is almost as intriguing as the implosion itself.

P is for Paydirt

“It’s the stories we cannot tell that kill us,” the late novelist Pat Conroy liked to say. Conroy knew this not only because he was one of the foremost writers of the family secrets novel but because he hailed from the land of the Murdaughs. “He often said that all of the kids in his family were damaged in different ways, not only by the abuse itself but by keeping it bottled up,” Conroy’s widow Cassandra King told me when we talked about the novel springing to life 40 miles from the Beaufort, South Carolina, home she shared with her husband. Some of the secrets that Conroy kept were told in his most celebrated novel, The Prince of Tides. Published in 1986, it is the tragic story of the Wingos, a Lowcountry family lorded over by an overbearing, abusive father. The Wingos are torn apart by a traumatic childhood event involving rape and bloody retribution that Tom Wingo (played by Nick Nolte in the 1991 movie) would later reveal to a New York City psychiatrist (Barbra Streisand) after his sister’s latest unsuccessful suicide attempt.

The story of the Murdaughs, King says, may be even more perverse than the fictional Prince of Tides. “It covers everything: good-old-boy politics in the Deep South, family dysfunction that would make Pat drool, murder, corruption, addiction… Yep, a Conroy novel. I cannot tell you how many people have said to me, ‘I’d love to hear Pat’s take on this.’ ”

He would surely focus on whatever toxic family secrets lay within the Murdaughs, she says, “since his family was coerced by the times, by his mother, by his father’s insistence that no one ever reveal anything about the abuse that went on.”

It’s the stories we cannot tell that kill us.

This is the tragic tapestry of some blueblood American families that, like their houses, seem so idyllic from the exterior but are so haunted within, a sad testament to the secrets these families keep, told over and over again.

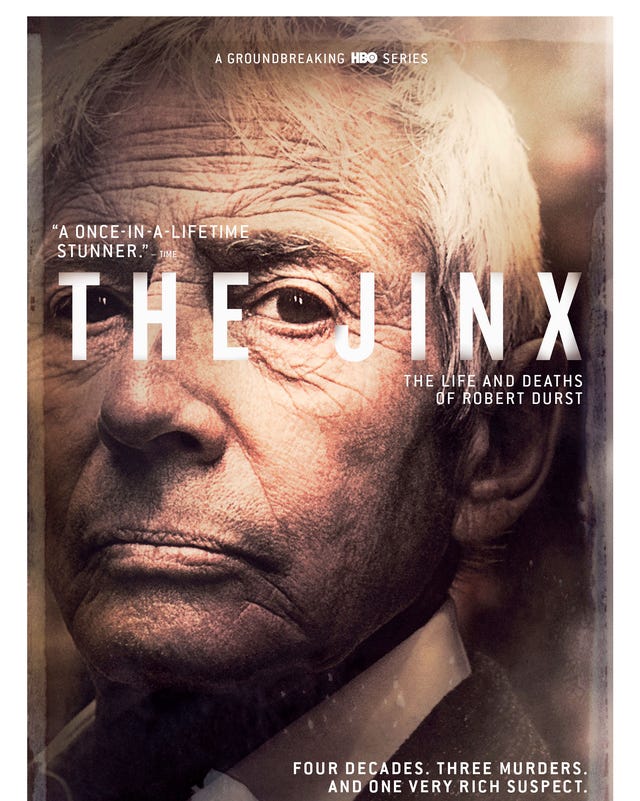

A first wife named Kathleen McCormack disappears on January 31, 1982, and a longtime friend, Susan Berman, is found murdered in her Los Angeles home. A man dressed as a woman hides out in Galveston, Texas, where he is arrested but acquitted for the murder and dismemberment of a neighbor, Morris Black. The name of the man eventually convicted of murdering Berman is known in New York not for high crimes but for revitalizing Times Square and creating the still-ticking National Debt Clock, the planning for which began before the technology was even available to create such a billboard-size device.

The name is Durst, which for 100 years has been associated with the “principles of innovation, integrity, community, and sustainability,” according to the family foundation website. Now it will also be remembered for a family secret, a festering wound still unexplained that caused family scion Robert Durst to be arrested for and convicted of murder.

The heir to one of America’s most famous fortunes funds the Villanova University wrestling program and builds an impressive athletic arena—and insists that he become the team’s head wrestling coach. An avid bird enthusiast, he writes several books about birds and establishes the Delaware Museum of Natural History, becoming its director. After the death of his beloved mother in 1988, he begins seeing ghosts in his home and soon becomes obsessed with one of the wrestling coaches whom he has hired, Dave Schultz, an Olympic gold medalist training for a comeback at the 1996 Atlanta Games. On January 6, 1996, the police are called. Schultz has been shot and killed, and the name of the man arrested for the killing will shock the world: John du Pont.

The list goes on, famous families brought low by infamous events. Different demons surely drove these privileged individuals, but in many ways their ignominious destinations are all the same. Now comes the family name that may, in the still evolving scandal, eclipse them all in the Myth of the Perfect Family: Murdaugh.

I’m still trying to get a piece of the action, either by parachute or sheer persistence, hoping to land in that sweet spot where you own all or part of a story. But in some ways we all own this miserable story and all the others that spring from the sordid ground of American family secrets in a world addicted to true crime. “When the Murdaugh trial is over, people will move on to the next high-profile case,” says Dr. Shari Schwartz, a forensic psychologist who studies how the public perceives criminals. “The victims’ loved ones, though, have already begun to serve a life sentence of pain and trauma.”

Like all the other families, the Murdaughs will be remembered not merely for the good other members of this once illustrious clan did but for the secrets they left behind. Told in the crimes of their progeny, as well as in books, podcasts, television series, and films, it will become part of the collective heritage of America, a nation whose secrets are all too often written in blood.

This story appears in the December 2022/January 2023 issue of Town & Country. SUBSCRIBE NOW