Estimated read time: 7-8 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SALT LAKE CITY — Getting treatment for asthma, lung cancer and other respiratory issues requires a long drive for a large portion of Utah's Native American population.

The majority of people living in 15 of the state's 29 counties reside in a pulmonology desert — defined as living at least an hour's drive away from the closest pulmonologist. A KSL.com analysis of census data and a county-by-county study on pulmonology deserts found that Native Americans are disproportionately impacted by these pulmonology deserts, with 26% of Utah Native Americans residing in one.

The one-hour drive time was used as a threshold to identify areas that lack proper pulmonary care because that distance can affect a patient's ability to seek care as they struggle to find transportation, afford the cost of transportation or take time off work, the study states.

But on reservations, an hour drive is often the status quo, says Jeremy Taylor — health program manager of the American Indian/Alaska Native Health Affairs Office at the Utah Department of Health. Growing up on the Navajo Nation, Taylor said even a grocery store was 45 minutes to an hour drive away.

"For me, an hour drive is nothing; that's a Tuesday," Taylor said. "I think if you ask these communities, they'll have pretty much similar notions of that distance in the sense that it's just the cost of doing business. It's just the way things are, and it's going to be take major change for that to change."

He added that long distances, although the status quo, are still a deterrent to seeking health care, especially preventive care.

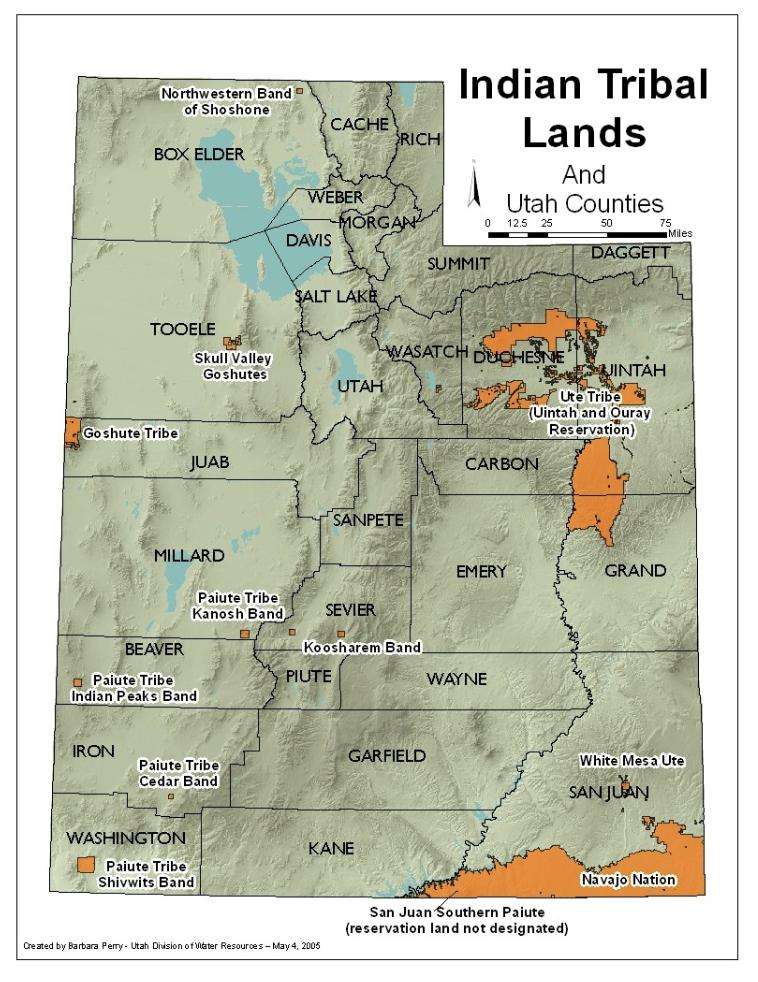

Utah's rural counties are more prone to be characterized as pulmonology deserts. Those rural counties also coincide with the locations of most tribal reservation land in the state, which Taylor says dates back to how and why reservations were created.

"Reservations weren't designed to be economic powerhouses; they're essentially prisons," Taylor said. "Why are reservations so far away from everything else? Because they were designed to be pushed away; they were designed to be managed by the military and then the Bureau of Indian Affairs; and they were meant to be tucked away out of sight, out of mind."

A poor foundation

The same factors that initially made reservations so enticing for the federal government today translate to widespread inequities.

Like most rural communities, recruiting and retaining health care specialists on reservations is a challenge. Taylor said the lack of infrastructure and access to resources limits who tribes can hire even if they have funding to do so.

The reservation system has also translated into social determinants that make Native Americans more susceptible to issues that would require pulmonology care, said Melissa Zito, Indian health liaison with the Utah Department of Health.

For example, because electricity is lacking on many reservations, residents often use coal and wood to heat their homes. Studies have found that individuals using those alternative heating sources at home have an increased risk for some lung conditions, such as lung cancer and asthma. Cigarette use, which is disproportionately high among Native Americans, can also be linked to factors that are widespread on reservations like poverty and poor housing.

"Access to services or resources and care has historically been a disparity since before the birth of the country," Zito said, emphasizing the importance of understanding the historical and current context of Native American health care.

Native Americans have legal rights to federal health care services unlike other ethnic and racial groups in the U.S. due to the unique relationship between the federal government and tribal governments. Today the Indian Health Service, a federal agency, provides medical services to tribal members and a number of tribes also provide health care independently of Indian Health Service.

Although the federal government has long assumed responsibility for providing health care, underfunding for it has been common. This often results in long wait times, with the Indian Health Service introducing wait time standards of 28 days or less for primary care and 48 hours or less for urgent care in 2017 as an attempt to reduce lengthy wait times for patients. For context, the Urgent Care Association found 92% of urgent care patients waited 30 minutes or less to see a provider.

Taylor said wait times along with historical mistrust and trauma shape the way Native communities access care.

"You have a lot of people that just don't want to access health care in that way unless it's dire. You don't have that kind of sense of your doctor is your friend or your doctor is the guy you go to to save you," Taylor said. "My grandpa doesn't like going to the dentist because back then they were just pulling teeth and then selling it to people down the road and people were buying Indian teeth and putting them in museums."

Some of that trust is being rebuilt, especially as tribes began to provide direct care, but apprehension around accessing care can have negative health outcomes. Chronic conditions aren't usually identified at an early stage, which in turn increases the risk for comorbidity (the simultaneous presence of two or more diseases or medical conditions), said epidemiologist Alex Merril with the Office of American Indian/Alaska Native Health Affairs at the Utah Department of Health.

This became especially apparent during the COVID-19 pandemic when Native American populations had higher death and hospitalization rates across the country and the Navajo Nation became a national hot spot.

"There is a higher burden of respiratory hospitalization and respiratory death among American Indians and Alaskan Natives," Merrill said, adding that this phenomena extends beyond COVID-19 to illnesses like influenza and pneumonia. "To say that's exclusively because of a lack of pulmonary specialist care — I think that's going too far, but it's a part of the bigger systemic, policy-driven atmosphere."

Although COVID-19 devastated many Native communities, it also provided a model of how to start breaking down existing health inequities since the urgency of the virus allowed resources to flow more freely to tribal organizations.

"One of the dark parts of COVID is because the death rates were so high, there was kind of a panic all around. That kind of forced the hand on a lot of these policies. But pulmonary (issues) aren't shooting off everywhere. It's like diabetes; it's one of those chronic conditions that doesn't rain in the news. So it's one of those things that definitely falls further and further down the list," Taylor said.

"That's what happens with these communities — they don't meet the threshold of need, so it just continues to exacerbate."

He added that the state can start addressing these issues by improving infrastructure to make tribal communities more physically accessible and increasing broadband to open the door for more telemedicine. Zito agreed that COVID-19 highlighted the importance of providing tribes with the resources they need.

"We know that if we provide tribal organizations and tribal health systems with resources, they can care for their communities and their people," Zito said. "We don't have to have that patriarchal sense of we will come in and give you the care — can we just give the resources that we would to a local health jurisdiction to a tribal organization or to a tribal community."