The male Y chromosome has disappeared from a species of rat, leading scientists to investigate how humans might also lose ours in the near future.

It's not all bad news for men though, as a paper published in the journal PNAS by scientists at Hokkaido University in Japan has discovered why this might not signal the end of males.

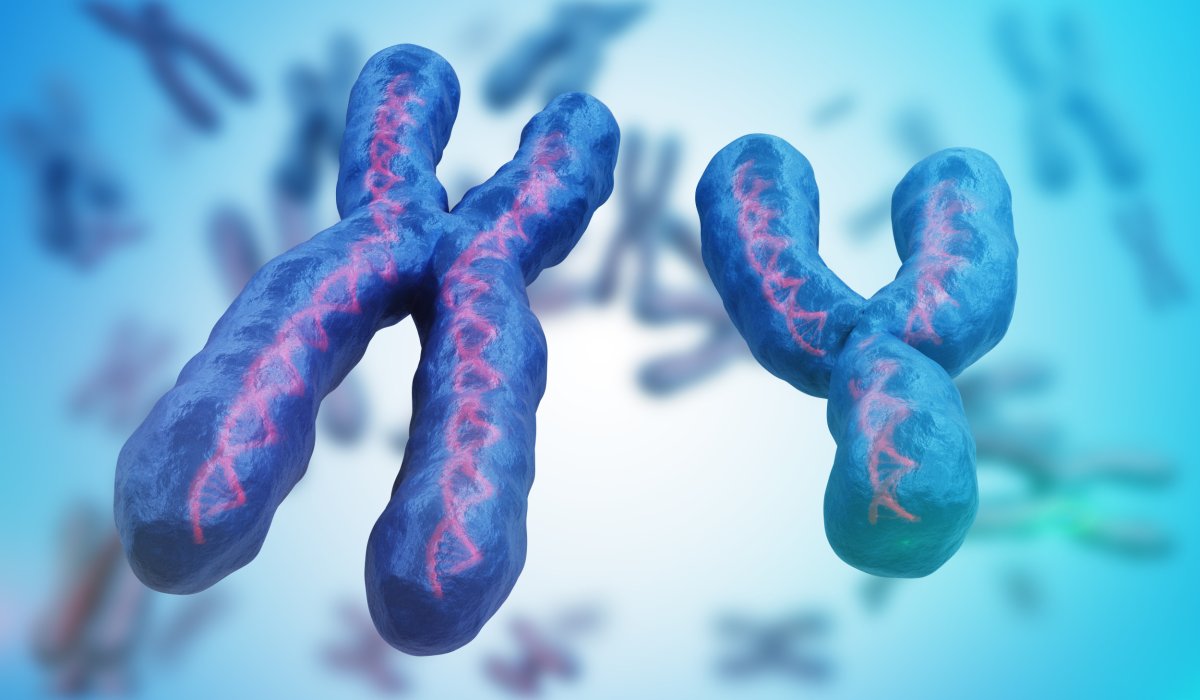

Humans have 23 pairs of chromosomes, one pair of which are the sex chromosomes. In biological females, there are two copies of the same type, giving them the genotype XX, while males possess a second, shrunken chromosome referred to as the Y chromosome, giving them XY.

"The mammal Y is a weird little chromosome with hardly any genes on it and a lot of DNA junk. But one of these genes is SRY, the male-determining gene," Jenny Graves, a sex chromosome geneticist at La Trobe University in Melbourne, Australia, told Newsweek.

"The Y makes no sense in terms of function, but is easy to understand in terms of evolution. The X and Y were once upon a time just an ordinary pair of chromosomes. Then one partner acquired a variant gene (SRY) that determines maleness," Graves said.

"Other genes handy in males accumulated nearby and to keep this male-specific gene package intact, it stopped swapping bits with the X. This meant it was stuck in a rut and couldn't repair itself, so it degenerated very rapidly, with many mutations and deletions, leading to its present pitiable state."

This has been observed to occur in Y chromosomes across the animal kingdom, with the smaller chromosome having completely gone in the spiny rat.

"The human Y is in the very last stages of degeneration, and the big question is how long till it, too, gets lost, and what will happen when it does. If it goes on degenerating at the same rate it has over the last 150 million years, it has only a few million years to go," Graves said.

The Y chromosome itself therefore doesn't flick the developmental switch that makes an animal grow male traits, rather the SRY gene on the chromosome starts the chain of events. All animals begin development as females: the SRY gene "turns on" other genes that lead to a fetus developing as male, including the SOX9 gene that triggers the development of testes.

In humans, the SRY gene is on the Y chromosome, so if the Y eventually disappears, will we have no more males? The PNAS paper, which investigates how the male spiny rat stuck around, shows us why males probably aren't going anywhere.

"Kuroiwa's team have minutely examined the genome of the Y-less spiny rats and discovered that a gene that is the target of SRY (called SOX9) has a changed sequence in its control region which is only in males. This makes sense, because an upregulated SOX9 would not need to be turned on by SRY," Graves said.

The researchers found that the male spiny rats had a duplicated region on their chromosome three, right next to the SOX9 gene itself. They also found that this duplication boosts the activity of SOX9 and thus effectively replaces SRY. Therefore, the spiny rats have evolved a way to make males using a completely different chromosome. The team estimates that this duplication evolved around 2 million years ago.

Despite the human Y chromosome's days being numbered, we will likely also evolve a way around this evolutionary hurdle, Graves said.

"When humans run out of Y chromosome, they might become extinct (if we haven't already extincted ourselves long since), or they might evolve a new sex gene that defines new sex chromosomes," she said. "Not necessarily SOX9; there are another 60-odd genes in the pathway that differentiates a testis in male embryos."

Even if males disappear, that might not be that big of a deal, Root Gorelick, a sex evolution researcher at Carleton University in Canada, told Newsweek.

"Females, by which I here mean organisms that produce large gametes called egg cells, can—in some species—self-fertilize, either by the egg nucleus fusing with another egg nucleus or by the egg nucleus spontaneously doubling all of its chromosomes," he said.

This parthenogenesis, or asexual self-cloning, has been naturally observed to occur in several whiptail lizard species, some geckos, Komodo dragons, snakes, as well as a few species of shark, spider, birds and invertebrates.

Whether humans eventually lose our Y chromosome in a few million years or not, the discovery by the Japanese scientists marks an important milestone in understanding how biological sex traits develop.

"This new paper plugs an important hole in our understanding of the Y chromosome. I have been waiting for this bit of data for 20 years, and it is very satisfying," Graves said.

References

Terao, M. & Ogawa, Y. Turnover of mammal sex chromosomes in the Sry-deficient Amami spiny rat is due to male-specific upregulation of Sox9. PNAS, 119 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.221157411

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Jess Thomson is a Newsweek Science Reporter based in London UK. Her focus is reporting on science, technology and healthcare. ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.