George Takei is on a mission. But this time the Star Trek actor is not boldly going where no man has gone before. Now he’s boldly going where too many men went before, to ensure history does not forget them.

Takei is about to star in the British production of the musical Allegiance, inspired by his childhood as one of more than 120,000 Japanese Americans forced into internment camps after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in 1941. Now a youthful 85, he says it remains the defining experience of his life – one that shaped him as an actor and an activist.

It’s 31 years since he played Sulu in the last of his six Star Trek movies, yet Takei is as prominent as ever. He is outspoken, has a huge social media following, and may be even better known these days as an author (in 2019 he published They Called Us Enemy, a beautifully illustrated graphic novel about his internment) and an LGBTQ+/anti-racist campaigner than he is for Star Trek.

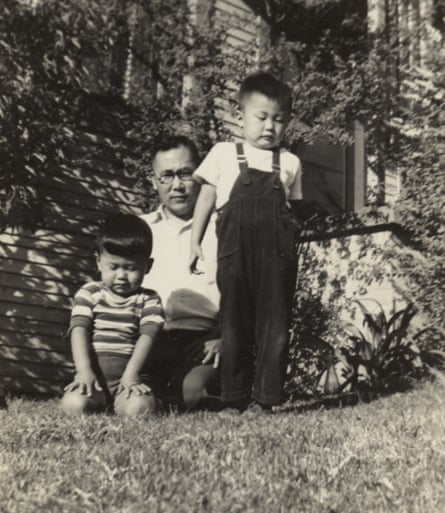

We meet in the penthouse of a London hotel overlooking the city’s landmarks. Takei, who is here with his husband, Brad, is slight, smartly dressed and bright as a sunny day – even when talking about such a bleak subject. He grew up in Los Angeles, one of three children born to a Japanese American mother from California and a father who grew up in Japan. Takei’s father became a successful businessman, running a high-end dry-cleaning store in LA. The family were looking forward to a happy and prosperous future. But that all changed with Pearl Harbor and the designation of Japanese Americans as “enemy aliens”.

It was three weeks after George’s fifth birthday, in 1942, that the military came for the Takeis. “My father came into the bedroom I shared with my younger brother, Henry, and dressed us hurriedly and told us to wait in the living room while they did last-minute packing. Henry and I had nothing to do, so we gazed out of the window and saw two soldiers march up our driveway. They carried rifles with shining bayonets on them and banged on the front door. We were petrified. I can never forget that terror of their banging.” You sense that every time he talks about it he experiences the terror anew. “My father came out of the bedroom and answered the door and they pointed the bayonets at him. Henry and I were frozen. My father gave us each a box tied with twine to carry. He had two heavy suitcases and we followed him out on to the driveway and stood there waiting for our mother to come out. When she finally came out, escorted, she had our baby sister in one arm, a huge duffel bag in the other and tears were streaming down her cheek.”

What Takei didn’t realise at the time was that the terror had been going on for months. Like other Japanese Americans, the members of his family had not been allowed to leave their home between 8pm and 6am. The day after the curfew was introduced his father discovered their bank account had been frozen. “My parents were spat on in the street and yelled at. My father’s car was graffitied with three letters – JAP.”

The Takeis were transported more than 1,600 miles to an internment camp in Arkansas and forced to live in a converted stable. “To take innocent people who had nothing to do with Pearl Harbor and categorise them as enemy aliens was outrageous. At five years old I was an enemy.”

Takei’s father spoke fluent Japanese and English and was elected a block manager in what was the US’s largest internment camp. In 1943, internees were asked to swear their loyalty to the US and forswear allegiance to the emperor of Japan. Takei’s parents refused to do so because the question wrongly assumed their loyalty was to Japan, while demanding allegiance to a nation that had horrifically mistreated them. The family were then sent to the harsher Tule Lake segregation centre in California for “disloyals”. It was here that many prisoners were radicalised, Takei says. Allegiance, in which he stars, explores how internment and the oath of allegiance divided families such as his.

The story of racism and radicalisation has so many echoes with recent times, Takei says. He mentions Donald Trump’s executive order banning people from certain Muslim-majority countries entering the US. “At least we had made progress by the time Trump got into office, because when he signed that executive order, acting attorney general Sally Yates refused to enforce it. When Roosevelt signed the executive order nobody stood up to him.”

He talks about how Trump incited hatred towards the Chinese American population by labelling Covid the Chinese virus. “After he racialised the virus, elderly Asian Americans were physically attacked. In Oakland, California, a young man ran to an old Thai man and smacked him down on the sidewalk. His head hit the concrete and he died.” Takei has astonishing recall of names, events and dates. On the rare occasion he does forget, Brad, a former journalist, fills in.

When the Takeis were released from internment they had nothing left. Japanese Americans were given $25 and a one-way train ticket to re-establish their lives. The family ended up living on Skid Row in downtown Los Angeles. As a child, Takei says, it was terrifying. “That was the worst place. Smelly, scary people with eyes like this.” He mimes a zombified junkie. “This guy was staggering towards us one day. And he got closer and closer and he just collapsed in front of us and barfed. My baby sister was four or five and she said: ‘Mama, let’s go back home.’” He pauses. “She meant ‘home’ behind a barbed-wire fence.”

Takei often refers to his parents – the strength of his mother and wisdom of his father. To his great shame, he says, he never appreciated their courage at the time. As a young man, he criticised his father for refusing to sign the oath of allegiance. “I was an arrogant, self-centred teenager. I must have been 13, 14. I said to my dad: ‘You led us like sheep to slaughter back into the camps.’ He had been through the anguish and horror and sense of rage, the whole burden of it, and this young punk was saying to him: ‘You led us like sheep to slaughter.’” Those words still haunt him today. “After I said that my father was silent. I felt terrible. Then he looked up and said: ‘Well, maybe you’re right,’ and he got up and walked into his bedroom and closed the door.”

Takei wanted to apologise, but it felt too awkward, so he told himself he’d do it the following day. It still felt awkward the following day, so he left it another day. He never did apologise to his father. “That’s one of the painful regrets I have.”

Takei went on to study architecture at the University of California, Berkeley, but quit his course after two years to follow his passion – acting. He transferred to the University of California, Los Angeles, where he graduated with a degree and master’s in theatre. In the 1960s, he performed in the civil rights musical Fly Blackbird. The cast sang at civil rights rallies and marched with Martin Luther King. On one occasion, he met King after performing at an event where the church leader was a keynote speaker. “At the end we were ushered down to the basement dressing room to meet Dr King, and this hand shook Dr King’s hand.” He looks downwards and smiles. “This hand didn’t get washed for about three days till my mother put her foot down and said: ‘You must wash.’”

In 1966, Takei was cast as Hikaru Sulu in the original Star Trek TV series. What he loved about the show was its idealism – all nations, races and extraterrestrial humanoid species working together for a better future. When I accidentally refer to it as Star Wars, he quickly corrects me. “We don’t make war – we make peace.” While the show was ostensibly pure entertainment, its originator, Gene Roddenberry, used its storylines to shine a light on contemporary realities such as racism, the cold war and the war in Vietnam.

Was the camaraderie on board the Starship Enterprise reflected on set? “Yes. Yes. YES,” Takei says passionately. “Except for one, who was a prima donna.” He is alluding to the show’s star, William Shatner, who played Captain Kirk. “But the rest of us shared a great camaraderie. One of the gifts from Star Trek was not just longevity but colleagues that became lasting friends. My colleagues were part of my wedding party in 2008. Walter Koenig, who played Chekov, was my best man. We asked Nichelle [Nichols, communications officer Uhura] to be our matron of honour but she said: ‘I am not a matron! If Walter can be the best man, why can’t I be the best lady?’ So she became the best lady.”

Leonard Nimoy, who played Spock, was his great campaigning ally. “Leonard was another politically engaged person. We had wonderful discussions.” Did they see themselves as socialists? “No, liberals. I didn’t realise what a loyal friend Leonard was till the latter part of our lives.” He cites the 2014 premiere of the documentary To Be Takei as an example. He had invited Nimoy, but assumed he would not make it because he was so ill. “Leonard came in a wheelchair. He was suffering from COPD [chronic obstructive pulmonary disease], and had a tank of oxygen to breathe in, and he parked in the back of the theatre and watched it. I was so touched. I went to thank him, but he was gone by the time I got there. This was just months before he died.”

James Doohan, who played Scotty, was another great friend. “Jim was my favourite drinking buddy. He was a great drinker.” Did he drink Scotch? “He was an Irishman and a Canadian, but he drank enough Scotch to qualify playing a Scotsman!”

Did any of the cast get on with Shatner? He shakes his head. “No, none of us.” Earlier this month, Shatner told the Times that he was astonished that 60 years on cast members were still moaning about him. “Don’t you think that’s a little weird? It’s like a sickness,” Shatner said, adding that Takei had “never stopped blackening my name”.

Today, Takei is reluctant to talk about Shatner. “I know he came to London to promote his book and talked about me wanting publicity by using his name. So I decided I don’t need his name to get publicity. I have much more substantial subject matter that I want to get publicity for, so I’m not going to refer to Bill in this interview at all.” He grins. “Although I just did. He’s just a cantankerous old man and I’m going to leave him to his devices. I’m not going to play his game.”

One question, I say: was he a cantankerous younger man? “He was self-involved. He enjoyed being the centre of attention. He wanted everyone to kowtow to him.”

Star Trek made Takei a household name, and he used his fame to remind people what had happened to Japanese Americans in the war. He testified at hearings to push for reparations and in 1988 President Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act, apologising for the US unjustly locking up a whole generation of Japanese Americans and granting surviving internees $20,000 each in compensation. Takei received his cheque three years later. “It was a massive thing. My cheque was signed by George HW Bush, in 1991. That whole amount went into the founding of the Japanese American National Museum.” Takei is a former chair of the museum.

Although Takei has been with Brad for the best part of 40 years, he didn’t come out until 2005. Ever since, he has campaigned on LGBTQ+ issues. He remembers first feeling attracted to boys when he was nine, had his first sexual relationship at 14 and found it exhilarating, and then for many years denied himself. He says it was hard enough being a Japanese American without being a gay Japanese American. “I knew that because we looked different we were punished and I didn’t want to be punished again for what I was feeling inside. I could hide it. So I started taking girls out for dates. I went out on double dates, but I was more interested in my buddy than my date.”

Takei adored the actor Tab Hunter, who was outed in the 1950s. “He was a matinee idol. Blond and beautiful, always taking his shirt off. He was my heartthrob. One of the scandal sheets exposed him as gay, and a torrent of abuse was thrown at him. I didn’t want to be like that. I must have been in my late teens. I ducked all these things.” Was he celibate? “Occasionally I went to gay baths and had very anonymous sex.”

Is it true that he met Brad at a running club? “Yes,” chimes in Brad, “and I was the most gorgeous member of the club. Drop-dead gorgeous!”

“He was!” Takei says. “Lean and taut.”

“When I first met George, there was a huge age difference,” Brad says. “I was in my early 30s, in the prime of my life. George was in his later 40s, almost over the hill! So he got my best years.”

“He was your toyboy?” I ask Takei.

“I was!” Brad says proudly.

Takei laughs. “No no no, I wouldn’t use that word. He was …” He looks for a suitable description. “My trainer for my first marathon.”

Takei says he worries that many of the gains in LGBTQ+ rights are now in danger of being reversed. In 2011, Tennessee senator Stacey Campfield introduced what became known as the “Don’t say gay” bill to ban teachers discussing homosexuality in classrooms. At the time, an appalled Takei suggested that they should substitute the name Takei for gay because it rhymed. “Now Ron DeSantis, the governor of Florida, is coming up with the same issue again.”

Takei is a busy man. He says he can’t see his activism easing up in the current climate. And he is writing more memoirs. Then there is the acting, of course – he can’t wait to be back on stage in London with Allegiance.

Before leaving, I ask for a photo with Takei. Brad asks if I can do the Vulcan salute – a raised hand with the palm forward and the thumb extended, while the fingers are parted between the middle and ring finger. I struggle, and ask if he can. “Oh yes! George wouldn’t let me be his husband till I could do this.” And now the pair are enjoying themselves. Takei shows me another trick. He wiggles his ears.

“He hasn’t done that for years!” Brad says. “Simon, you’re a very special person! To bring out George’s ear wiggle is very special.” He looks at Takei. “Go on, George – do the George Takei funny face to camera.” And now Takei scrunches his face into a magnificent gurn and the two of them roar with laughter.

Perhaps it’s not surprising that Takei is still so boyish. His grandmother lived until she was 104, and he says her favourite hobby was collecting birthdays. Does he hope to be around that long? He nods. “Rather than celebrate birthdays, I celebrate every day. Each day is a gift.” He looks down over London from the penthouse, taking in the old and the new on a wet and windy day. “Ah, this wonderful English greyness!” he hymns. “This city is dynamic. It’s constantly changing. It’s alive.” The same could be said of George Takei.

Allegiance is at Charing Cross theatre, London, from 7 January to 8 April