For a story that was first told 2,300 years ago, the myth of Atlantis has demonstrated a remarkable persistence over the millennia. Originally outlined by Plato, the tale of the rise of a great, ancient civilisation followed by its cataclysmic destruction has since generated myriad interpretations.

Many versions have been intriguing and entertaining – but none have been as controversial as its most recent outing in the Netflix series Ancient Apocalypse.

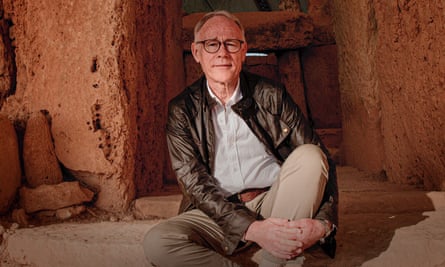

Presented by the author Graham Hancock, the programme argues that a once sophisticated culture was destroyed by floods triggered by a giant comet which crashed on Earth, a disaster that inspired the legend of Atlantis, it is claimed.

According to Hancock, survivors of the calamity spread round the world – which was then populated by simple hunter-gatherers – bringing them science, technology, agriculture and monumental architecture. We owe everything to these near godlike individuals, it is claimed.

For good measure, Hancock – who has been promoting these ideas in his books for decades – argues that archaeologists have deliberately covered up this catastrophic vision of civilisation’s spread and accuses mainstream academia of its “extremely defensive, arrogant and patronising” attitudes.

These stark claims have helped the series reach the top of viewing lists on both sides of the Atlantic, to the chagrin of archaeologists who, for their part, have denounced Ancient Apocalypse on the grounds that it provides little evidence to support its grandiose claims and for promoting conspiracy theories dressed up as science.

Flint Dibble, an archaeologist at Cardiff University, described Hancock’s basic thesis as “flawed thinking”. Archaeologists don’t hate him, as he claims. “It is simply that we strongly believe he is wrong,” says Dibble in an article in The Conversation last week.

The confrontation is intriguing and raises many issues of which the most basic is the simple question: why has the story of Atlantis – compared with other ancient myths – maintained its popularity for so long? What is the essential attraction of the tale?

For answers we only have to look at the works of Tolkien, CS Lewis, HP Lovecraft, Conan Doyle, Brecht and a host of science fiction writers who have all found the myth an irresistible inspiration.

As to the suggested location of this lost civilisation, these have ranged from the Sahara to the Antarctic and countless places in between.

Nor is Hancock the first to suggest the destruction of a once great civilisation led to the flowering of culture elsewhere. In 1882, the maverick US congressman and popular writer Ignatius Donnelly published Atlantis: The Antediluvian World which argued that a highly complex, sophisticated culture had been wiped out by a flood 10,000 years ago and claimed that its survivors had spread round the world teaching the rest of humanity the secrets of farming and architecture. Sounds familiar.

Then there were the Nazis. Many swore by the idea that a white Nordic superior race – people of “the purest blood” – had come from Atlantis. As a result, Himmler set up an SS unit, the Ahnenerbe – or Bureau of Ancestral Heritage – in 1935 to find out where people from Atlantis had ended up after the deluge had destroyed their homeland.

And that, in part, explains why the myth of an ancient, lost civilisation is so useful. It is a basic tale of a rise and fall that can be corralled and exploited for all sorts of causes. Plato meant his tale to be an allegory. Atlantis was destroyed by the gods who had grown angry with the hubris displayed by its inhabitants and so destroyed it. Don’t get too big for your boots, in other words.

But Hancock – who describes himself as a journalist presumably to avoid being called a pseudo-scientist – takes the story to a new controversial level in suggesting that survivors of such a deluge were the instigators of the great works of other civilisations, from Egypt to Mexico and Turkey to Indonesia. As Dibble states, such claims reinforce white supremacist ideas. “They strip indigenous people of their rich heritage and instead give credit to aliens or white people.” In short, the series promotes ideas of “race science” that are outdated and long since debunked.

As to the likely site of the original Atlantis, the serious money goes on the destruction of the Greek island of Santorini and its impact on Crete and puts the blame on volcanic eruptions – not errant comets, as Hancock argues.

In addition, while Ancient Apocalypse suggests that destruction happened 12,000 years ago, most proponents of the alternative view believe it occurred around 1630BC when the island of Santorini exploded in one of the most violent volcanic events in human history.

Fourteen cubic miles of rock were hurled into the atmosphere, triggering huge tsunamis and a hail of ash that would have destroyed the Minoan civilisation which then flourished on Crete.

It was this cataclysm that was remembered more than 1,000 years later in Plato’s time. He attributed it to a civilisation that he called Atlantis, little knowing how his brief description of a lost culture would resonate so strongly – and often controversially – through the ages.