SAN LUIS, Colorado — When I hear my grandmother or anyone else from northern New Mexico or southern Colorado speak Spanish, it feels like a warm, familiar blanket from my childhood. Sadly, that blanket is quickly unraveling, and soon I’ll only have threads of it left.

It’s a depressing reality as elders like my grandmother are among the last living keepers of this beautiful form of Spanish. As they leave this world, the language of this land gets a little more silent and a little more scarce.

“This dialect is so amazing. It's so unique. It's so precious,” Dr. Devin Jenkins, a linguist, told me in Boulder a few weeks ago.

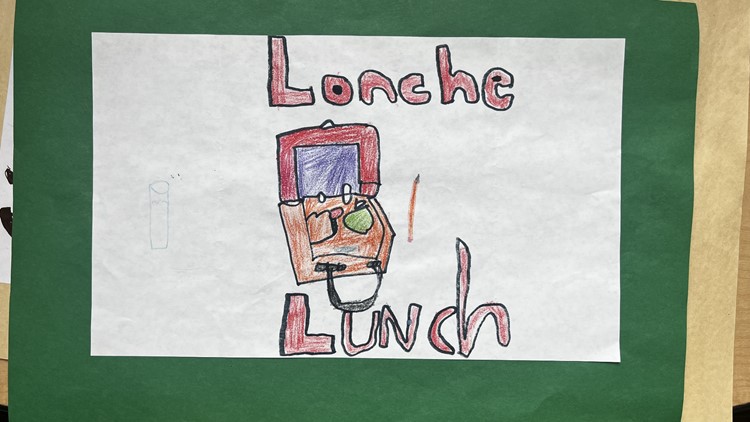

We got together to have a discussion about the dialect over a friendly lonche, which means lunch in the dialect and is pronounced lone-che.

Jenkins is the head of the Department of Modern Languages at the University of Colorado Denver and has studied the dialect for more than 20 years.

“It is every bit as valid as any other variety of Spanish out there,” he said.

When I hear Jenkins speak of the dialect, it’s clear he has admiration and passion for the language. He shared a sobering prediction on the dialect’s last decades of life.

“It’s this treasure that we've got -- probably, in two more generations, we're probably just not going to see anymore. Max, I’d say, 50 years,” he said.

Why is it unique and why is it fading away?

The Spanish spoken for hundreds of years in this region first arrived in the 1500s, when Spaniards and mestizos from Mexico brought words from the old and new worlds as they settled in what is now New Mexico.

Their Spanish language was already a mix of old words from Spain and indigenous words like tecolote (owl) from the Nahuatl peoples of Mexico.

As mestizos and colonists clashed and then blended with Native American peoples in the Southwest, more indigenous words were added to the mix.

The isolated and remote area became an incubator of the dialect. In the 1800s, a flood of English speakers began to arrive, which influenced the language heavily.

“It's not really an immigrant population. English came to them,” Jenkins pointed out during our lunch.

The ever-evolving dialect is now a wonderful soup of Spanish, Native and English words, quite reflective of the region’s complex heritage.

It’s a form of Spanglish like no other.

While I understand only some of the dialect, I instantly recognize its accent with its blended bounciness of vowels and soft use of consonants.

The form of Spanglish has its amusing twists on English words like troca (pronounced tro-kah, for truck), and daime (die-meh, for dime).

This is the dying language of my ancestors.

While I have black-and-white photos that provide a visual window of what my ancestors looked like, I will no longer hear them through the breath of my grandmother after she inevitably leaves this world.

Alzheimer’s disease is robbing her memory and her voice.

She’s 93 years old and is among the last of my family to speak the dialect fluently.

“As younger generations gravitate toward English and assimilate toward English, there's just no functional need anymore for that Spanish," Jenkins said. "It's simply a heritage need at this point. ‘I want to hang on to this because it's part of who I am.’”

As my grandparents began raising a family in the 1950s, they rightfully prepared their children for an English-dominated life. They gave them anglo-based first names as college became family dreams.

No names like Jose, Maria and Guadalupe are found among the younger generations in my family.

And while I grew up hearing the dialect and learning its unique phrases, the language of my ancestors has reached the end of its full life within my family.

This is common among so many other families from the region.

For this story, I interviewed Buddy and Josie Lobato, who married in San Luis 68 years ago. They grew up speaking the dialect and still speak it at home in Westminster.

They told me they were punished as children for speaking Spanish at school, which was perhaps some of the first efforts to diminish the language.

“They would hit us with the ruler on our hands,” said Buddy, who turned 90 years old last month.

“It was kind of a shock when you went to school and all of a sudden you had to learn a new language,” Josie said.

The two eventually moved to Denver and felt out of place, even in their own country, as newcomers to the city.

“When we first came to Denver, they used to make fun of us because of the way we spoke English,” Buddy said, with Josie adding that they had an accent.

Can it be kept alive?

In San Luis, I met with Audrey Rael’s fourth-grade class of eight kids to get a sense of the dialect’s existence among the town’s youngest generations.

Every child in the class has heard some of its words, but they don’t speak it fluently. Their parents and grandparents are among the last to know it.

Rael said she tries to keep some of the language alive.

“I find myself using the language in class," she said. "I’ll tell my students to go get that brook from the trastero (cupboard). Different words that I grew up saying, I will tell my students.”

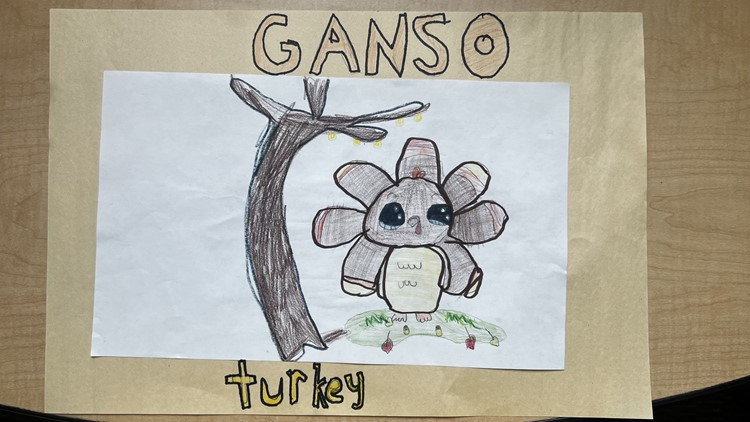

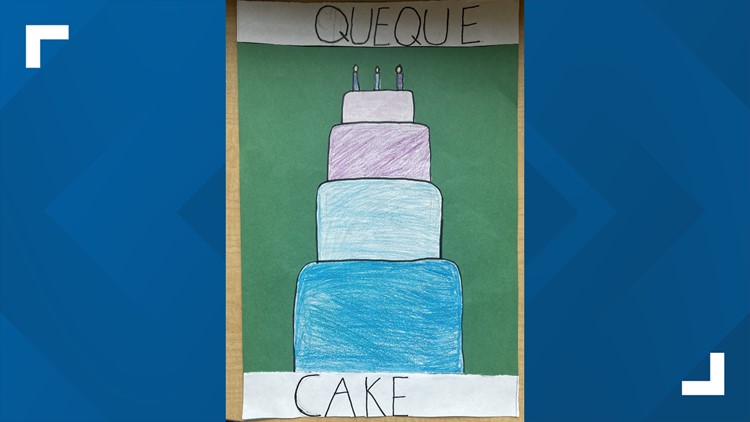

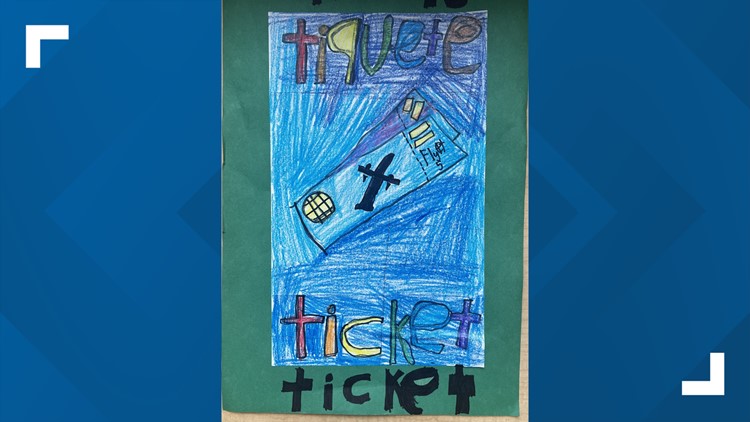

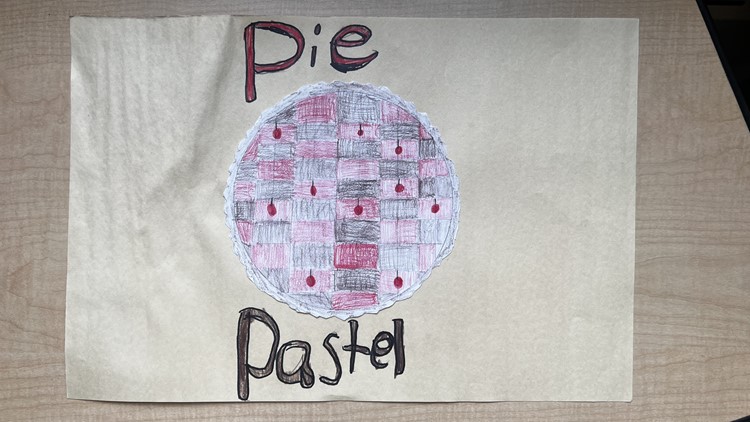

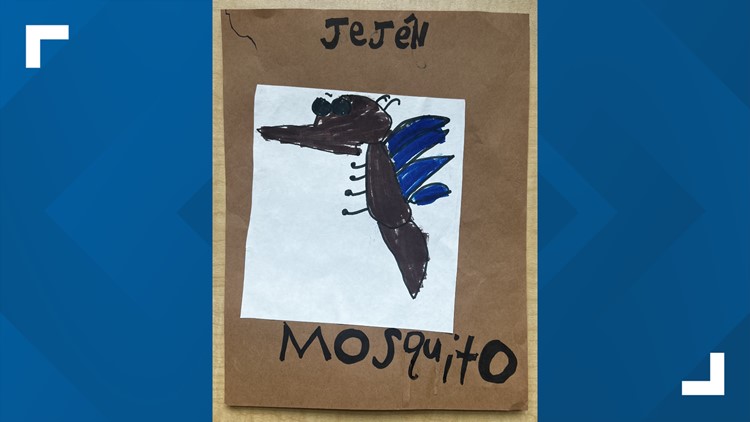

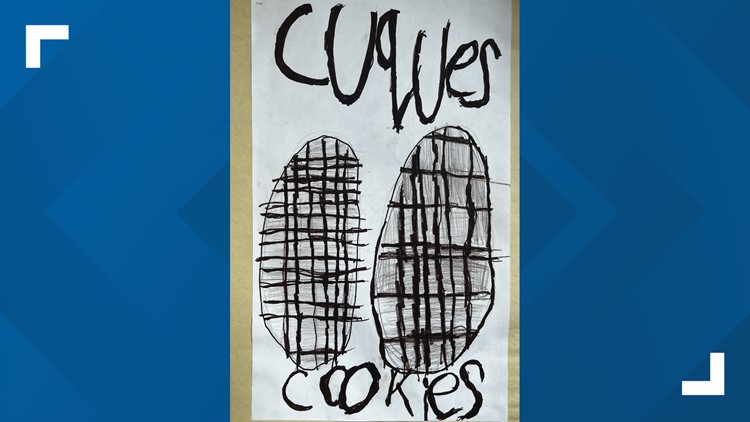

For my visit, the children agreed to do a fun assignment by sharing some of the dialect’s Spanglish words through art. Each piece of art has the word written in English and Spanish from the region.

School children share words in art from a unique Spanish dialect

During the end of our lonche, I asked Jenkins if there was any way this dialect could survive and be saved.

“You'll get families that really try to keep it alive and things like that," he said. "And I love that. I applaud that effort, but it's an uphill battle.

“We're losing it. It's going away,” he said. “What it is — it’s a beautiful thing, and boy, it is worthy of all of our admiration and affection. And if you have any inkling at all toward the Spanish language, go and learn about it, while it’s still here."

At my home in Denver, I still use the dialect’s words and nursery rhymes with my toddler. She answers to jita (daughter) and loves the Spanish music from the region. She'll grow up knowing some words. But that's all I can give her.

For now, the language is still alive and found among our elders, but sadly, I find myself trying to hold on to it as a child does with their blanket.

If you have any information about this story or would like to send a news tip, you can contact jeremy@9news.com.

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: Hispanic Heritage