Beauty Devi, 34, an unofficial coalminer, lost her husband in a mining accident who died while extracting coal from an abandoned tunnel. Devi has two sons: Vishal Kumar, 13, and Naman Kumar, 11.

Beauty Devi showing a picture of her husband, who died in an accident when the roof of an abandoned mine collapsed.

She wakes up early, before sunrise, and heads towards an abandoned tunnel of an inactive coalmine. It takes almost two hours to walk there from her home.

She spends the entire day extracting coal. The mines are extremely risky because of underground fires. Toxic gases fill the tunnels, making it unfit for breathing. She has to walk almost 300ft inside the tunnel to work.

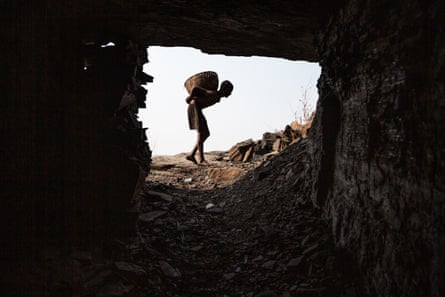

Devi extracting coal from an abandoned coal tunnel. The roofs of these tunnels can collapse anytime.

After reaching the tunnel, Devi starts extracting coal from a shelf using her axe. Afterwards, her and her two sons fill buckets with coal and return to their home by evening. They carry litti and chokha, a kind of stuffed bread and mashed potato, for their lunch.

Devi’s younger son, Naman, likes studying and is in grade 6. Sometimes, he doesn’t go to the mine and instead attends school. But when his family needs him, he is forced to skip school and go to the mine with his mother and older brother.

Devi and her family members prepare coke in the evening time from the coal they extracted in the morningto sell.

After returning home, Devi and her sons burn coal to make coke, a type of fuel, in to sell to local teashops and restaurants. They earn under $3 a day. Their house is engulfed in smoke for long periods.

Beauty preparing coke in the evening from the coal she extracted in the morning so as to sell it.

Devi counts her earnings from selling the coke.

The tunnels are the remnants of abandoned opencast mines. When the mining companies no longer consider them viable, they abandon them. The local villagers then create unauthorised tunnels into the mine to extract the remaining coal. Sometimes the roofs of the tunnels collapse due to heavy rainfall. Underground fires have also killed many people.

Vishal Kumar, 13, Devi’s elder son, carrying a bucket full of coal from an abandoned coal tunnel. The roof of the tunnel is so low that you have to bend down to enter and leave.

Vishal, face blackened with coal soot, at work.

Vishal Kumar drinks water while working.

Beauty’s elder son, Vishal, recovering after inhaling toxic gases.

Opencast coalmines are a threat to the environment. Toxic air pollutants released from the mines contribute greatly to global heating. In India, 80% of the country’s electricity comes from coal – the country is third in terms of carbon emissions.

Jharia coalmine helps boost India’s economy and also serves as an earning opportunity to the local villagers, but what they earn barely keeps them alive. The locals are so poor they often consider selling their children to the mine mafias or sending them to work as labourers for extra income.

Children here regularly suffer from malnutrition, skin diseases, and other conditions. The constant exposure to pollution from living near the mines has turned their skin pale and their eyes yellow.

During the monsoons, the air in Jharia becomes thick with toxic gases.

The mines themselves are even more dangerous. Poisonous gases such as carbon dioxide, sulphur dioxide, carbon monoxide and nitrogen oxide are rampant. The gases cause skin and lung diseases such as tuberculosis and other respiratory issues.

The underground fires make the situation even more hazardous. Accidental deaths are commonplace. The fires regularly trigger sinkholes, causing homes and water pipes to collapse, and workers are often trapped or killed in the mines. The constantly burning subterranean fires have forced some locals to abandon their homes and relocate.

The fires raging underground in Balugada are forcing some locals relocate.

In an operational mine in the Jharia region, an unofficial miner brushes his teeth.

Jharia is a hive of unauthorised mining activity. The villagers, including children, have no other work options than to labour in the mines for a pittance. They barely manage two meals a day, and cannot afford to send their children to school. Some of their children are recruited into warring gangs and the mining mafias make their lives hell.

Beauty Devi sitting at sunset.

The Joan Wakelin Bursary offers £2,000 for the production of a photographic essay on an overseas social documentary issue. The bursary was established in 2005 in memory of distinguished documentary photographer and honorary fellow of the society, Joan Wakelin.

The bursary funds new projects only. It does not support on-going projects, neither does the bursary support projects requiring travel to or within war zones.

Information on how to apply for the 2023 bursary will be available on the Royal Photographic Society and the Guardian websites early next spring.