Khiara Bridges remembers the exact moment she lost faith in the Supreme Court. At first, at the start of Donald Trump’s presidency, Bridges—a professor who now teaches at UC–Berkeley School of Law—held out hope that the court might be “this great protector of individual civil liberties right when we desperately needed it to be.” Then came 2018. That June, the justices issued Trump v. Hawaii, which upheld the president’s entry ban for citizens of eight countries, six of them Muslim-majority. Suddenly, Bridges told me, she realized, “The court is not going to save us. It is going to let Trump do whatever he wants to do. And it’s going to help him get away with it.”

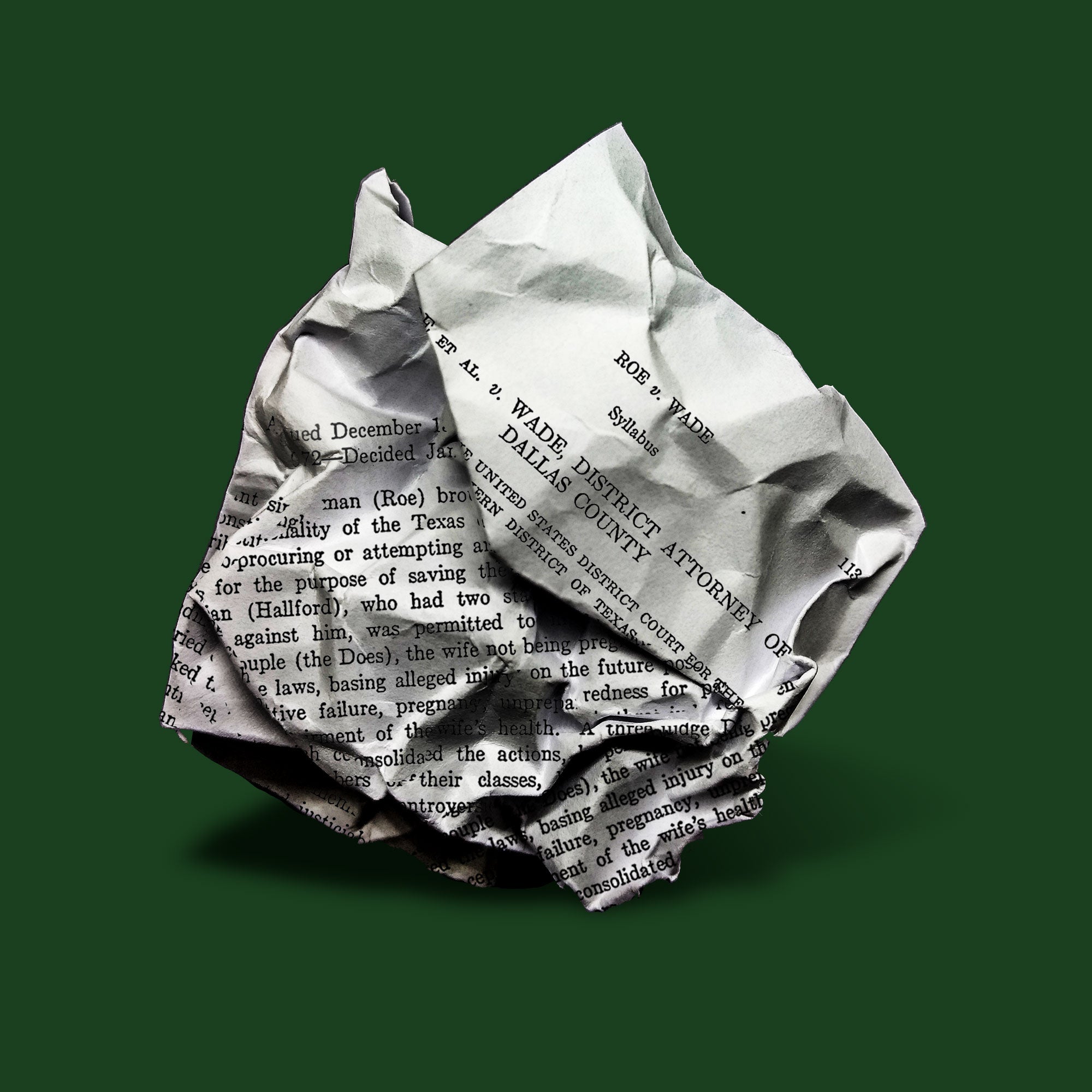

Four years later, the justices completely shattered whatever remaining optimism Bridges could muster about the court by overruling Roe v. Wade in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. When the decision came down on June 24, she got a migraine for the first time in a decade. The image of the court as a majestic guardian of liberty was, she concluded, “a complete lie.” And it wasn’t just about her own personal feelings, either: Now she had to teach her students about the work of an institution that made her sick to contemplate.

Bridges is not alone. At law schools across the country, thousands of professors of constitutional law are currently facing a court that, in their view, has let the mask of neutrality fall off completely. Six conservative justices are steering the court head-on into the most controversial debates of the day and consistently siding with the Republican Party. Increasingly, the conservative majority does not even bother to provide any reasoning for its decisions, exploiting the shadow docket to overhaul the law without a word of explanation. The crisis reached its zenith between September 2021 and June 2022, when the Supreme Court let Texas impose its vigilante abortion ban through the shadow docket, then abolished a 50-year-old right to bodily autonomy by overruling Roe v. Wade. Now law professors are faced with a quandary: How—and why—should you teach law to students while the Supreme Court openly changes the meaning of the Constitution to align with the GOP?

A version of this question has long dogged the profession, which has fought over the distinction between law and politics for about as long as it has existed. For decades, however, the court has handed enough victories to both sides of the political spectrum that it has avoided a full-on academic revolt against its legitimacy. That dynamic changed when Trump appointed Justices Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett to replace far less conservative predecessors and created a Republican-appointed supermajority, a coalition further aided by the appointment of Neil Gorsuch to a seat that should have been filled by Barack Obama. The cascade of far-right rulings in 2022 confirmed that the new court is eager to shred long-held precedents it deems too liberal as quickly as possible. The pace and scale of this revolution is requiring law professors to adapt on several levels—intellectually, pedagogically, and emotionally.

Like Bridges, Serena Mayeri, a professor at University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School, traces her recent disillusionment to Trump v. Hawaii. The fact that Kavanaugh’s predecessor, Justice Anthony Kennedy, sided with Trump “left me deeply shaken,” Mayeri said. “It was weeks before I could bring myself to read the opinions in full.”

Shortly thereafter, Kennedy announced his retirement, further rattling Mayeri. “I’ve always considered myself a deeply patriotic person,” she said. “My family comes from Eastern Europe and Iran; on both sides I have relatives who took refuge in the U.S. and taught me to see America as a beacon of hope, however flawed our attempts to live up to our ideals.” Mayeri was crossing the border into Canada when the Hawaii decision came down, and she suddenly felt she did not want to return. “For the first time in my life, I didn’t want to go home to my own country, a country I barely recognized.”

Mayeri’s outlook did not improve as the court took a wrecking ball to her areas of expertise, especially reproductive rights. That doesn’t mean she is seriously considering quitting academia. “There have certainly been moments over the past few years when anything other than direct political action felt like rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic,” she said. “But being a law professor is an incredible privilege, and I love almost every minute of it.”

In the classroom, Mayeri will try to teach decisions like Dobbs “in broader contexts, such as the alarming global erosion of democracy” and “the convergence of anti-democratic forces that enable the court to thwart majority will.” For law professors, these rulings “have unsettled the foundational premises of our professional lives,” she told me.

If this all sounds a little overstated, consider one example of how disruptive the court’s sprint to the right has been. Perhaps the most famous facet of legal education is the bar exam, which almost every prospective lawyer must take to practice law. The exam does not incorporate the Supreme Court’s most recent decisions; those taking the exam in 2022 were not tested on 2022 rulings. That means exam takers must pretend U.S. law was static over the previous year, or risk answering questions incorrectly—by asserting, for instance, that abortion access and Miranda warnings are still a constitutional right. The more the law shifts in any given year, the more confusing the test. By next year, however, the 2022 term will be incorporated into the exam. Consider what this means for a student who took Constitutional Law in their first year of law school: The rights they learned are affirmed under the Constitution are no longer protected by the time they’re entering the field.

Bar examiners, like law professors, need stability to test students’ knowledge. But this Supreme Court’s conservative majority has disclaimed stability as a virtue of the law. It is upending the ground rules that guided so many generations through law school.

The Supreme Court has had turbulent and alarming periods in its history before. But since the 1950s, the legal academy has told a particular story about American law, one with clear heroes and villains. The Supreme Court was the hero, vindicating the Constitution’s grand guarantees of liberty and equality for all, abolishing segregation while guarding against authoritarianism. It was the great bastion of freedom, the protector of democracy, the champion of civil liberties, the pure and high-minded manifestation of our nation’s noblest values. Now, it is reshaping into an antagonist of many of those values, facilitating democratic backsliding while rolling back long-settled rights.

The problem, it’s worth emphasizing, is not that the Supreme Court is issuing decisions with which left-leaning professors disagree. It’s that the court seems to be reaching many of these conclusions in defiance of centuries of standards, rejecting precedent and moderation in favor of aggressive, partisan-tinged motivated reasoning. Plenty of progressive professors have long viewed the court with skepticism, and many professors, right- and left-leaning, have criticized the reasoning behind certain opinions for decades. But it’s only in recent years—with the manipulation of the justice selection process combined with clear, results-oriented cynicism in decisions—that the problem has seemed so acute that they feel it affects their ability to teach constitutional law.

“It’s hard to think about your own profession—the things you were taught, the things you believed in—abruptly coming to an end in rapid succession,” said Tiffany Jeffers, a professor at Georgetown University Law Center. “It’s hard to ask a law professor to dismantle all the training they had. It’s a difficult, emotional, psychological transformation process. It’s not easy to upend your life’s work and not trust the Supreme Court.”

Jeffers told me that after the flurry of hard-right rulings this June, many professors had their “own personal grieving period.” But they quickly turned toward “grappling with how we teach our students” to understand the Supreme Court’s reactionary turn. “I’m not changing what I teach,” she said. “I am restructuring how I challenge students to think about the law, how it’s a biased set of historical norms based on the past that people in positions of power have had influence over.”

Despite the “shock and grief” of this term, Jeffers has not questioned her decision to become a law professor after serving as a prosecutor for 10 years. She believes her new position actually gives her more reach. “There is power in being a lawyer,” she said. “If students aren’t trained to use that power for good—well, that’s why we are where we are now.”

To conservative ears, this statement may smack of liberal bias. After all, a triumph of the conservative legal movement (including many conservative professors) has been to cast law as perfectly neutral, to make believe that it does not reflect subjective value judgments of those who write and interpret it. The mere idea of using law “for good” is suspect, as is a professor’s classroom criticism of certain Supreme Court decisions.

In reality, much of the legal academy does have a bias—it just isn’t of the liberal or conservative variety. Instead, law professors tend to have a profound trust in institutions, and process, and specifically the institution of the federal judiciary. This faith can limit the terms of the debate—in many ways, it already has. Many professors who personally lean left also cherish the courts and are aghast to see them exploited to promote a political agenda. Indeed, many of the professors I spoke to for this article would not connect their personal political leanings to their reverence for the court. Or at least they wouldn’t have until recently.

Every professor has to decide how much of their aversion toward the current court they are willing to reveal in class. The professors interviewed for this piece reported that, by and large, students on the right did not object to in-class editorializing. There seem to be two reasons: First, these professors took pains to teach each case down the middle before offering their own views, and even then, they always allow for pushback through class discussion. Second, many offer their own views only in elective classes for 2L’s and 3L’s, playing it by the book when teaching 1L’s (who don’t get to pick their classes). Bridges told me she assumes students in her electives are interested in her personal views—and if they aren’t, they can drop the course.

Plenty of legal academics, no matter how they lean politically, try to refrain from introducing their beliefs into the classroom teaching at all. For these professors, Dobbs v. Whole Women’s Health is something of an ultimate test of straight-faced detachment at the lectern. Dobbs overturned a half-century of precedent and ended the right established in Roe v. Wade. Jolynn Childers Dellinger, a professor at Duke Law School, teaches privacy law. For her entire career, that included Roe v. Wade. Now, she’ll have to teach whatever comes next. Like many professors, she intends to overhaul her classes to accommodate the new decisions. Professors often tweak their syllabuses each semester, but this year, the flood of precedent-busting decisions has forced many to reconstruct theirs from the ground up. This fall, instead of teaching her students about Americans’ right to privacy, Dellinger will teach them about how the government could monitor and punish Americans who attempt to access reproductive health care despite the new laws.

But this term’s rulings pushed her to reconsider more than her syllabus.

“I have always perceived of the law as a tool for justice,” Dellinger said, “and my faith that the law is being used toward that end has definitely been shaken by this Supreme Court. It is honestly hard to know what to say to students entering this profession at this time as we witness the Supreme Court upending constitutional principles” and “stripping an entire class of people of fundamental rights without so much as a minimal effort to acknowledge the consequent harms.”

Not all progressive constitutional law professors are in the same boat. Eric Segall, a professor at Georgia State College of Law, told me that he “lost faith in the Supreme Court long ago.” Segall subscribes to legal realism, which rejects the notion that courts apply pure logic, free of prejudices, to reason out every legal dispute. It recognizes that politics plays an undeniable role at a Supreme Court that is shaped by partisan elections. And it rejects a vision of the law as some majestic set of neutral principles that can be applied evenhandedly, without regard to political pressure and public opinion.

For progressive legal realists, this term felt like a bleak confirmation of their worldview. David Cohen, a professor at Drexel Kline School of Law, said he didn’t expect SCOTUS “to do anything other than be the political branch of government that it is.” He has long taught students that “doctrine and precedent” matter less than the justices’ “ideologies, values, politics, and biases.” Cohen added that “what this version of the court is doing is not really any different than past courts”; it’s just more conservative.

Expounding legal realism in the classroom requires a delicate balance: Professors have an obligation to teach blackletter law, doctrine, precedent. But that also happens to be everything that the current Supreme Court is upending. A professor must say what the court claims it’s doing, then explain what it is actually doing, which is often something completely different. This technique can disillusion students, leading them to ask why they’re bothering to learn rules that can change at any moment.

Even law professors who maintained confidence that the Supreme Court would rise above politics are reconsidering their view after this term. “I have generally, up until now, resisted the cynicism of the ‘new legal realists’ that the Supreme Court isn’t a court, it’s just a policy council,” said Steve Sanders, a professor at Maurer School of Law. “I want my students to believe that legal argumentation, precedent, facts, and doctrine matter.” In the aftermath of this term, though, “it’s becoming increasingly difficult to deny that major constitutional decisions are almost purely about politics.”

This realization compelled Sanders to reconsider aspects of his teaching style. “I think one of my strengths as a teacher has been that students, both conservative and progressive, see me as an honest broker who rarely injects his own opinions into teaching,” he said. “But there comes a point when you can’t have integrity as a teacher and teach these cases honestly without noting their serious flaws.” Dobbs, for instance, “is screamingly, unapologetically activist. It gives no respect to settled societal expectations, reliance interests, or the meaning of the Constitution as it’s been lived through the lives of actual people for the past 50 years.” And it brought him to his “breaking point.”

But what, in the end, can a professor do when confronted with a decision that fills him with disgust? “Emotionally, I can rant about it,” Sanders said. “Intellectually, my job is to lead and empower students to discover and assess for themselves whether or not the opinions are persuasive and honest.”

It’s difficult to overstate the impact of Dobbs on law professors who maintained reverence or respect for the Supreme Court, even if it was only a little. Mary Ziegler, a professor at UC–Davis School of Law, did not have high hopes for the decision. As a legal historian, she never took a gauzy view of the court as a hero of history; her “defining moment in law school” came when she read Buck v. Bell—an odious 1927 decision upholding mandatory sterilization of the “feeble-minded”—and thought, “That’s not the majesty of the law.” (She has a knack for understatement.)

Ziegler is perhaps the nation’s foremost expert on the history of abortion rights in the United States, so she saw Dobbs coming well in advance. Yet when the decision was finally handed down, she told me, “I felt horrible. The way Alito wrote the opinion felt like such a complete slap in the face. It felt disrespectful, insulting, indifferent to the views of a lot of people, almost mocking. For me, that made it a lot worse. I imagine there are a fair number of women who experienced it that way.”

Ziegler will likely teach this “insulting” decision for the rest of her career. But even though these professors may be depressed or repulsed by the court’s conservative revolution, paradoxically, they all feel lucky that they can teach it. Much of this positive attitude is driven by their admiration and respect for students, who—pretty much everyone agreed—face rougher sledding than they do. Students confront a legal system in a crisis of legitimacy led by an extreme and arrogant court. Still, they must slog on, most gathering substantial debt as they go, pretending that “law” is something different from politics, a higher realm of reason and rationality where the best arguments prevail.

Somehow, it’s going better than you might expect. Multiple professors told me that our faltering, captured judiciary has not paralyzed their students. Rather, it has made them more skeptical of the courts from Day One, more attuned to the political and social forces that have always propelled judges toward particular outcomes. Not many of Bridges’ students, for instance, are as “bright-eyed and bushy-tailed” as she was in her first year.

In my own conversations with law students, I’ve noticed this shift, too: It feels like every year, a larger percentage of the incoming class arrives with deep suspicion of the Supreme Court and other sacred cows of the legal profession. Every professor I spoke with for this article stressed that they do not merely tell students what to think; as Ziegler put it, “I want to leave space for students to figure it out and not tell them I have all the answers, because I don’t.” Instead, they are experimenting with more candor about their own views and creating room for productive debate that, at the end of the day, really is a core component of a good legal education.

If left-leaning law professors do not quit en masse or embrace torpid nihilism, it will be because their students give them a reason to keep returning to the classroom. For those reaching the end of their career, though, the idea of rejiggering established syllabuses to teach the work product of this court may be too much to bear. My father, Nat Stern, retired from a 41-year career at Florida State University College of Law in May. He loved his job, and his students voted him “professor of the year” so many times that he stopped counting. I was surprised when he announced that he would step down from teaching at 67, a relatively young age within the academy. When I asked him why he decided to retire, he told me that he had no desire to explain the Supreme Court’s conservative revolution as the product of law and reason rather than politics and power.

“For the bulk of my career,” he said, “I’ve felt I could fairly explain rulings and opinions that I don’t endorse because they rested on coherent and plausible—if to me unconvincing—grounds. In recent years, though, I’ve increasingly struggled to present new holdings as the product of dispassionate legal reasoning rather than personal agendas.” I used to think my dad would keep teaching forever. I’m sure his students did, too. And maybe he would, in a different world, one where Republicans did not ruthlessly manipulate the court’s membership to achieve their policy goals. In this world, though, faced with a conservative supermajority on the Supreme Court for years to come, retirement was not a tough call.

“I’ve immensely enjoyed my career as an instructor of constitutional law,” he told me, reflecting on four decades of joy in the classroom. “But the direction of the court gives me no incentive to extend it.”

Law professors who remain years away from retirement do not have this escape hatch. They are already back in the classroom, bracing for another brutal term of precedent-smashing rulings. It’s not all bad: The students give them hope, keeping them “afloat in darker moments,” as Mayeri put it. Students have clued in to what’s going on, yet they persist in their legal education because they believe there’s still a real chance for change. There’s inspiration in that.

In a recent class, Bridges candidly discussed the enormous challenges facing the legal profession today. The students were angry and fearful, yet they readily offered ideas to help tackle current crises head-on. “I always leave class feeling great,” Bridges said. “It’s like therapy.”