I recently discovered that if you walk around New York City while carrying a colonial-era musket, you get a lot of questions.

“You gonna shoot some redcoats?”

“Where’s your well-regulated militia?”

“What the hell, man?”

Questions aside, a musket can come in handy. When I arrive at my local coffee shop at the same time as another customer, he tells me: “You go first. I’m not arguing with someone holding that thing.”

Why am I carrying around a 1795 firearm? Well, it’s because I’m deep into Project Constitution. I’ve pledged to live by the US constitution as strictly and literally as possible. I want to see what it’s like to be the ultimate originalist.

I got the idea after the US supreme court’s latest controversial term. As you might know, it’s the most conservative court in decades. It overturned Roe v Wade, saying that the constitution does not guarantee a right to abortion. It bolstered gun rights and took power away from the Environmental Protection Agency.

This is, in large part, because several justices adhere to a philosophy called originalism in some form or another. The main gist of originalism is that we should follow the original meaning of the constitution as it was understood when it was first implemented in 1789 (or, if the decision involves one of the constitution’s amendments, whenever that was ratified).

So I figured: what if we took this to its logical endpoint?

To be fair, there are many versions of originalism, and no originalist would go as far as I do. Originalists argue that the constitution doesn’t require you to opt for muskets over modern guns. Instead, a good originalist takes the centuries-old principles of the constitution and applies them to the current day, using history and tradition as a guide. So the right to privacy, originally meant to stop the constable banging on your door, now applies to your smartphone.

Fair enough. But it seems to me – and many other observers – that the court’s originalists can be pretty stingy when it comes to updating, especially if it involves women’s rights, gay rights or environmental regulations. “One of the dangers of originalism is that the people who practise it can easily get too frozen in history, and I think that’s what some members of the court did this term,” says Glenn Smith, a constitutional law professor at California Western School of Law. “They’ve let their hidebound sense of history overcome a reasonable originalist approach.”

More than that, originalism can be wildly inconsistent. Sometimes a certain constitutional right is interpreted as narrowly as possible – Clarence Thomas, the most hardcore originalist on the current supreme court, doesn’t believe the “liberty” recognised in the 14th amendment can expand to include gay marriage, since the drafters never conceived of gay marriage. Other times, a right can be stretched to the breaking point. Most originalists say the “right to bear arms” covers muskets as well as AR-15 semi-automatic rifles, even though they are arguably vastly different.

So what if I try to be consistent? What if I always apply the narrowest interpretation, avoiding the hubris of assuming I know what the country’s founding fathers would have thought? What if I adhere to the strictest version of what was written in 1789 – or, in the case of the later amendments, what was written in 1791 or the 1870s? After all, I want to be prepared in case originalism gets even more extreme.

“My Month of Living Constitutionally” led me on a weird, enlightening and often deeply awkward journey. I handed out pamphlets, I fetched my own water, I annoyed my wife.

Here is the tale.

Congress shall make no law … abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press – Amendment 1 (1791)

As a journalist, I’ve always been grateful to the founding fathers for the right to free speech. But I’ve learned the 18th-century idea of free speech was startlingly different from today’s – both in how we communicate and in what is allowed.

First, there’s the method I use to express free speech: Twitter. Fortunately for the founding fathers, theirs was a world of paper and ink. It seems to me Twitter is like the AR-15 of speech. It’s another animal altogether. To be safe, I decide to stick to the 18th-century version of Twitter: pamphlets.

I order a quill pen and parchment paper, and scratch out a dozen analogue “tweets”, one on each piece of yellowed paper.

I go to midtown Manhattan to hand out my mini-pamphlets. It’s harder than I thought. Most people skilfully avoid my gaze, looking at the pavement, the skyline, anywhere but my face.

Finally, I approach a woman waiting for the light to turn green and read her my tweet out loud: “I find it egotistical that we capitalize the word ‘I’ but not ‘he’ or ‘she’ or ‘they’.”

“Yeah,” she says. “I guess that’s interesting.”

“Do you want to take my pamphlet?”

“No, I do not.”

As mixed as the reaction is, it still feels better than the Twitter cesspool. Just seeing people face to face has a healthy effect.

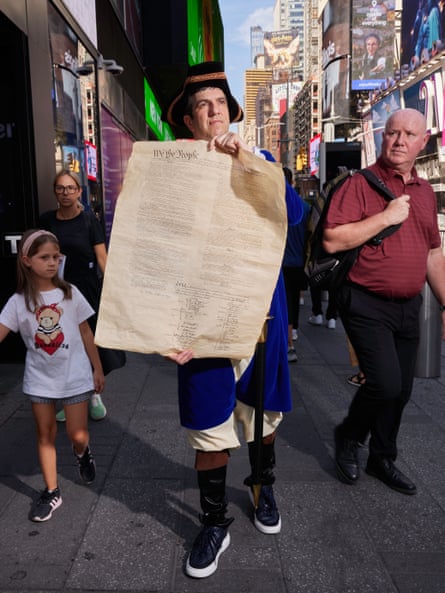

Now I should mention one other thing: to get fully into the founding fathers’ mindset I was wearing an Alexander Hamilton costume. This is not constitutionally mandated. But I’ve found that there are advantages to dressing the part. The outer often affects the inner. With my tricorn hat, I somehow felt more dignified (even though I was mistaken for both a pirate and Napoleon – but, oddly, not Hamilton).

Back in constitutional times, there was another big first amendment difference: the content of speech was much more restricted. “Governmental limitations of expressive freedom were commonplace,” law professor Jud Campbell wrote in the Yale Law Journal in 2017. “Blasphemy and profane swearing, for instance, were thought to be harmful to society and were thus subject to governmental regulation.”

It wasn’t quite Stalin’s Russia, but it wasn’t a free-for-all. You could be arrested for insulting God or trashing the president. What’s more, according to influential originalist judge Robert Bork, the first amendment only referred to “prior restraint”, meaning that the government couldn’t stop you from buying a printing press. But it could punish you afterwards for what you published.

This will be fun, I think. I get to be a puritanical censor to my kids and blame it on the constitution. When my son drops his iPhone and says: “Goddammit!” I reply: “That is unprotected speech. Say ‘Gosh darn it!’”

Then I go on Twitter (I know, I’m a hypocrite) and open an account under the name OriginalDude89.

I reply to people calling President Biden or Republican senator Lindsey Graham traitors. “You realise your seditious comments are not protected by the first amendment, at least as it was conceived of by the founders, right? You could be prosecuted if this were the 1790s. Please remove.”

One responds: “LMFAO whatever dude!”

Nor shall any State … deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws – Amendment 14 (1868)

The 14th amendment, which guarantees equal protection, is beloved by liberals, who believe it extends to gay rights and women’s rights, among others. Most liberals adhere to a philosophy called the living constitution – the idea that rights and meanings in the constitution evolve to fit the times.

Uber-originalists have a much narrower view. The 14th amendment was ratified after the civil war, in 1868, and should therefore only apply to the rights as understood in 1868. It was passed to guarantee rights to Black men, recently freed from slavery. Antonin Scalia, the famously conservative justice who served until his death in 2016, argued that the constitution didn’t say anything about gender-based discrimination.

In 1868, women couldn’t vote, and in many states couldn’t hold certain jobs. This is going to be tricky.

For instance, just five years after the ratification of the 14th amendment, the supreme court upheld Illinois’ decision to deny a law licence to a woman based on her gender. I email the lawyer who works with my book publisher.

“Dear Michelle:

For the duration of this experiment, I’m afraid I can’t deal with you on legal matters related to my books and articles. Nothing personal!

I’d be happy to deal with any male colleagues of yours in the meantime.

Thank you.”

I feel like a huge dick pressing send.

Likewise, in 1868 married women in many states couldn’t sign contracts. My wife Julie is president of an events business, and prepares and signs several contracts a day.

I tell her that, from the point of view of the constitution’s drafters, this activity isn’t protected. I might have to take over.

“Great!” she says, moving from her desk to the couch and picking up a magazine. “I’ll be over here if you have questions.”

Thus commence several hours of me trying to navigate confusing and irritating paperwork. I have to ask Julie so many questions about cancellation policies and pricing that she eventually fires me.

“This isn’t helping me,” she says.

In addition to sexism, I have to address racism. The original 1789 constitution contained notoriously racist parts that slave-holding states insisted be included. For instance, enslaved Black people only counted as three-fifths of a person for the purposes of calculating congressional representation.

Luckily I don’t have to follow that particular egregious rule. It was overturned by three post-civil war amendments.

But of course that doesn’t mean the 14th amendment’s promise of “equal protection” immediately got rid of constitutionally permitted racism. For instance, Black men could vote, but in many states they could not marry a white woman.

As legal scholar Elie Mystal writes in Allow Me to Retort: A Black Guy’s Guide to the Constitution: “The people who ratified the 14th amendment hated Black people marrying white people … Either our understanding of the 14th amendment ‘evolved’ to include a rejection of racist anti-miscegenation laws, or it didn’t. If the 14th amendment doesn’t evolve, Alabama could force people to submit ‘pure-blood’ certifications from Ancestry.com before issuing marriage licenses.”

It was not until 1967 that the supreme court ruling lifted intermarriage bans nationwide. Thankfully, today even the most ardent originalist would say interracial marriage is protected. But since I’m being strict as possible about hewing to the original vision, I guess I shouldn’t. Which is a horrible thing to contemplate.

I call up my sister. She is married to a man from Peru with mixed Latin and indigenous heritage. I explain that her marriage, from an 1868 viewpoint, would probably have been seen as an interracial marriage, which would have been banned in some states.

“So American history has a lot of racist assholes – not a huge surprise,” she says. “You know I want to be supportive, but this is crazy.”

Agreed.

“I guess I could send you back your wedding gift,” she suggests.

That could work – I’ll hold on to the wine glasses I gave her till the project ends.

“Actually I think I won’t send them,” she adds. “You can come and pick them up if you want.”

after newsletter promotion

At least the pamphlet escapade had some redeeming value. This was just plain terrible.

A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed – Amendment 2 (1791)

It’s time to return to the second amendment. Originalists argue that 2A didn’t just apply to muskets. Scalia wrote in a 2008 opinion that the amendment’s “central component” was about individual self-defence – the amendment applies to “bearable arms … not in existence at the time of the founding”. So it can be stretched to include today’s weapons.

Ironically, when it comes to guns, some liberals argue we need to hew more closely to the original worldview. They say muskets and AR-15s are just too different. One shoots four rounds a minute, the other can shoot dozens. Liberals argue it’s like taking a law written for bicycles and applying it to an 18-wheeler truck. “The fact that we use the same word to describe them is almost an etymological coincidence,” says Peter Shamshiri, co-host of 5-4, a podcast about the supreme court.

To avoid hubris, I’m going to stick with muskets and exercise my 2A rights by getting one. I’ve never owned a gun, though I was on the rifle team at my summer camp, so I guess that’s something.

I call up a Texas store called Collectors Firearms. I have my eye on a model 1795 flintlock musket. It’s crazy expensive – $2,000 – but the cheapest one I could find. A salesman named Nico answers the phone. I tell him I’m interested, but I want to make sure it works.

“Yes, it should fire. But since it’s an antique, we don’t recommend shooting it.”

“Why not?”

“There is a chance of catastrophic failure.”

That doesn’t sound great. But what does it actually mean? Basically, Nico explains, it could explode in my face.

Well, nothing ventured, nothing gained. I give him my credit card number.

Three days later, the musket arrives. It’s 5ft – almost as tall as my wife. I know it was once a deadly weapon – it may have even killed someone – but I’m struck by how elegant it is: dark wood, intricate metal fixings. It’s also heavy. I’m amazed the revolutionary soldiers were able to carry these all day. And though I’m not a gun guy, I also have to acknowledge that this object helped the Americans win the revolution. I’m surprised by my desire to keep this historic relic even after my project ends.

So how do I shoot it? I watch a bunch of YouTube videos. It’s quite a process. Take out a cartridge (paper tube filled with lead ball and powder). Bite off top. Spit. Open pan. Pour some powder in the pan. Pour rest of powder, along with ball and paper into gun barrel. Take out ramrod. Push ball down. Return ramrod. Cock. Aim. Fire.

I think I’ll need to cancel my dinner plans.

But first, I’ll need the lead balls and old-style black gunpowder. (I’m told not to use modern gunpowder under any circumstances.) I call a Minnesota-based company that sells vintage ammo. I get 25 balls. But the gunpowder? Well, the problem is, the factory is out of commission right now. It’s being “rebuilt from their latest mishap”.

Note to self: don’t get a job at a vintage gunpowder factory.

So for the time being, I have to be satisfied with just carrying my unloaded musket around. Which I do. I realise my experience would have been vastly different if I weren’t a white man. But I find walking around by turns exhilarating and stressful. Exhilarating because on some animal level I feel safer, more powerful. Which is insane, because it isn’t even loaded. And stressful because, well, what if I run into someone with a gun from this century?

I have a team of constitutional advisers, and I ask one of them what he thinks of my musket. He points out that a strict originalist interpretation of the second amendment could favour the musket. But it could go the exact opposite direction: it could encourage citizens to buy the latest military gear from Lockheed Martin.

“A lot of the rhetoric from the right about the second amendment is about the potential to resist government,” says Shamshiri. If that’s true, even semi-automatic guns aren’t enough. You won’t be able to face down an invading air force and tanks with just guns. “That interpretation serves as an argument for access to military-grade weaponry,” he says. “The point is, there’s no concrete originalist interpretation. It can be taken in different directions.”

I don’t have the budget for a Stinger surface-to-air missile.

No State shall … deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law – Amendment 14 (1868)

I’ve been hoping to use Project Constitution in my perpetual battle with my kids over screen time. And I think I found my secret weapon: good old amendment 14.

The amendment says that no state shall deprive any person of, among other things, “liberty”. But what is liberty? Well, a 1923 supreme court ruling defined liberty as, among other things, “the orderly pursuit of happiness by free men”.

So the constitution enshrines our right to pursue happiness. But it only enshrines ways to achieve happiness that were approved of when the 14th amendment was ratified in 1868.

I knock on my son’s door. “The bad news is, no electronics for the duration of my constitution project. The good news is, I got you this.”

I hold up a cup-and-ball that I’d bought online – a 19th-century wooden toy where you try to get a ball on a string into a cup.

“Also, no Netflix, since such entertainment is not protected by the original intent of the first amendment,” I say. In the 18th century, some states banned all theatrical performances because of “their morally corrupting influence”, Jud Campbell wrote in the Yale Law Journal.

My son ignores me.

Which allows me to explore another part of the constitution – the eighth amendment’s ban on “cruel and unusual punishment”.

How can I punish my son in a non-cruel, non-unusual way? Well, let me look to history and tradition. Up until the 1820s, the pillory – the wooden contraption with holes for the head and hands – was a frequent way to shame criminals.

According to extreme originalism, if a punishment was common during the founding era, it’s not cruel or unusual today. For instance, Scalia said the death penalty is constitutional partly because it was common when the eighth amendment was ratified in 1791.

Now I know the eighth amendment is meant for government not personal use, but I’m kind of on a roll. I do a Google search for “pillory” and find there’s quite a lively subculture of people who enjoy pillories. Many of the photos of models in stockades wouldn’t pass 18th-century obscenity laws. The cheapest pillory I find is $50 and made of cardboard.

“OK, hands and head in,” I say when it arrives a few days later.

My son shakes his head.

“Just do it for my project,” I say.

“Fine.”

He stays there for 30 seconds, then tears out of it like the Hulk. But he does later spend a few minutes with the cup-and-ball, so that’s something.

I spent my month frantically trying to abide by other original principles. The constitution talks about the right to assemble, but does that extend to Zoom meetings? I’m not so sure. So I meet colleagues in person.

The constitution says the government cannot do searches and seizures without reason. But they only talked about searches of physical spaces. So are my computer files protected? Maybe the government could seize thousands of documents from my computer without violating the constitution. (Not that I have any secrets about foreign nations’ nuclear capabilities.) The only solution I can think of is to print out all of the laptop’s documents, keep the pages and delete the digital files. Which was a massive waste of time and black ink cartridges. I gave up after 200 pages.

The constitution also says that no soldiers shall be quartered in my house without my consent. I put an ad on Craigslist offering a free room to a member of the military – if and only if I decide they’re cool after an interview. The only response is from an architecture student from Turkey.

So how do I feel? First, I feel grateful that I don’t live in 1789. Despite the recent erosion of our civil liberties, it still feels freer than it was in the powdered-wig era. I’m also a fan of modern plumbing.

Second, I know that originalists might say that I lived by an unfairly exaggerated version of originalism. And that’s probably true. But at the end of this, I’m not totally anti-originalist. Originalism comes in many flavours. I’m just opposed to the way some are practising it now.

Originalism came to the fore in the 1980s as a way to stop what the conservatives saw as the liberal supreme court’s overreach. They worried the court – which approved of affirmative action and the right to abortion – was untethered and just willy-nilly making rulings that aligned with their politics. The liberals were “legislating from the bench”.

So originalism was the proposed solution. Judges should put aside their views and objectively focus on the words of the text. As the conservative Federalist Society puts it: “Originalists analyze the text and evidence first, then conclude what result logically follows.” As opposed to the “living constitutionalist” camp that decides “on a correct result and then use the text and precedent to support their initial assumption”.

Sounds good, right? The irony is that, to many observers, originalism ended up falling prey to the exact same fallacy. Originalists seem to reason backwards. Witness that originalist decisions usually – not always, but usually – align with conservative principles. (A rare exception is Scalia’s opinion that the first amendment protects burning the American flag.)

Maybe this can’t be avoided. Humans – especially ones who went to law school – are brilliant at rationalisation, motivated reasoning and selective history.

But originalism doesn’t have to be so frozen in the past and politically motivated. You could define originalism as the idea that we should respect the founders’ broadest and best principles – equal protection and dignity, for instance – and apply those principles to modern problems. I like the sound of that. The key is to be super broad with those principles and avoid what the liberal justices, in their dissenting opinion on the recent abortion decision, called a “pinched view of how to read our constitution”.

Yes, it will require cherrypicking the best principles. But as my mother once said to me: what’s wrong with picking cherries, as long as they are the sweet ones?