On Jan. 27 1942, just 51 days after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, members of the San Diego City Council voted unanimously in favor of a resolution that called for the FBI to remove Japanese Americans from the city.

"It is urged upon said Federal Bureau of Investigation that said enemy aliens be removed from this vicinity, since their presence here is cause for great concern on the part of the City of San Diego due to existence of known subversive elements," the resolution read.

Some 40 years later, Kay Ochi, a third-generation Japanese American who is now president of the Japanese American Historical Society of San Diego, began a fight to demand that the U.S. government apologize and pay reparations to the Japanese Americans imprisoned during WWII. As a member of Nikkei for Civil Rights and Redress in Los Angeles, she started by learning the stories of the people, like her parents, who suffered in the camps.

"History really didn't talk about what happened to the Japanese people, only that they were removed," Ochi said. "The more we learned, it just not only angered us, it filled us with sadness about the stories that we had never learned and heard, because our parents didn't speak about it. They were too busy trying to recover."

In 1981 the Federal Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, established by former President Jimmy Carter, came to Los Angeles.

"The commission went all over the United States, nine different major cities with Japanese Americans. They collected over almost 800 testimonies," Ochi said. "But the bottom line is the report that they were required to present. They concluded that our incarceration was based on (racial) prejudice. They added wartime hysteria and the failure of leadership."

Ochi said what she learned from the testimonies of 150 Japanese Americans during the Los Angeles hearing propelled her further to fight for reparations.

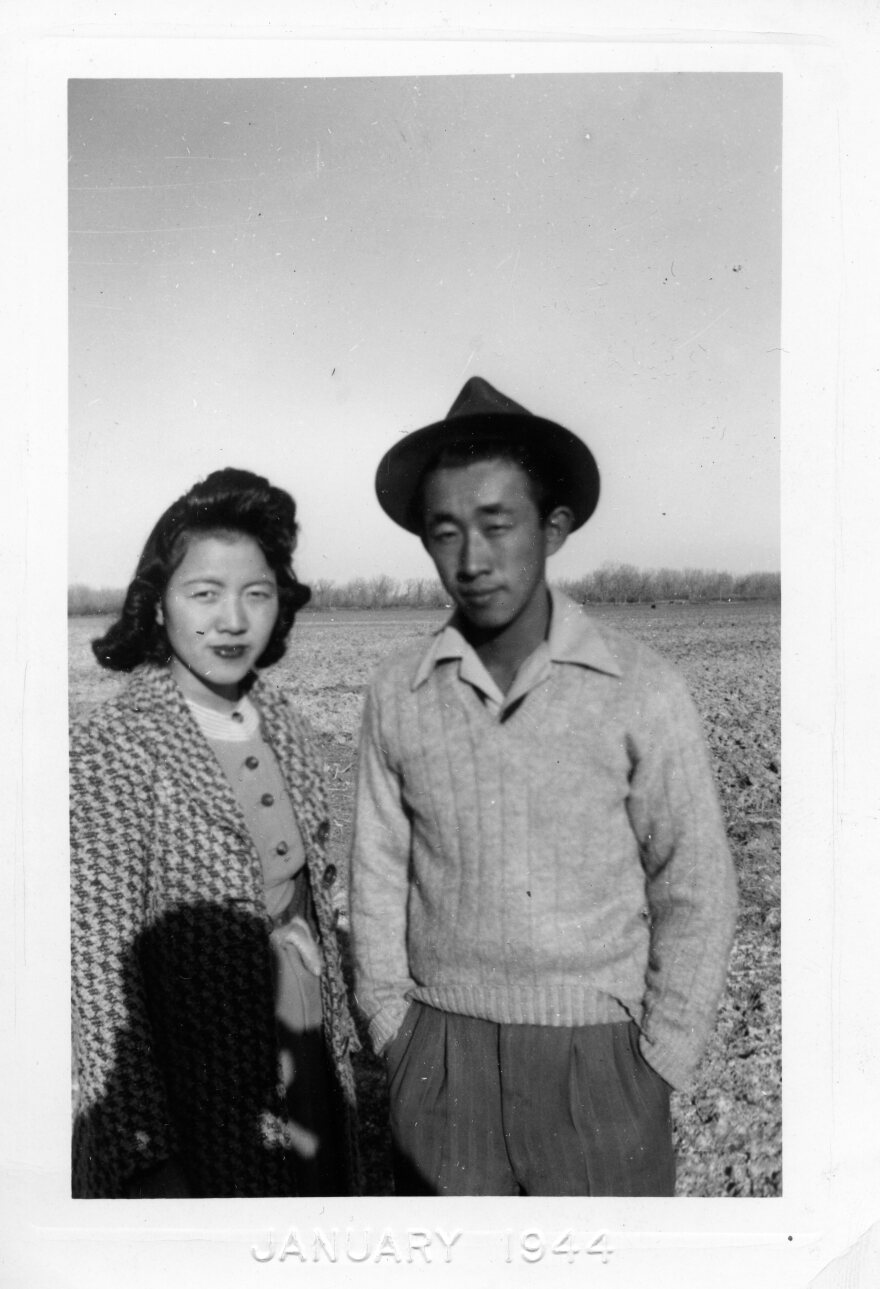

Ochi's parents, Ichiye and Akiji Ochi, were 20 and 21 when they were forcibly removed. They spent three years incarcerated in an internment camp in Poston, Arizona along with many other people of Japanese descent from San Diego. In 1942 a traveling minister married them in one of the camp's barracks.

"They made the best of it. And that would be the theme of our community," Ochi said. "They were proud Americans, so proud to be Americans, that there was a sector who felt that the best thing to do to show our pride and our loyalty to this country is not to make a fuss, but after the war, they were able to return to Barrio Logan."

Ochi said her parents' ability to eventually reestablish themselves in San Diego was thanks to the kindness of neighbors.

"Everything had been taken from us except for those places that were protected by good people," Ochi said. And one particular family, Japanese American family, had a home and another had a small market right on Logan Heights. And through the kindness of neighbors, the Nava family, that home and business was protected."

Ochi's parents lived with another Japanese American family for about 10 years. Her father worked in the fishing industry and her mother in a tuna cannery. Eventually they were able to save enough money to buy a home in Chula Vista.

In 1988, after more than four decades of being stripped of their dignity and forced to carry the shame of being targeted as the "enemy" because of the actions of Imperial Japan, the United States apologized for forcibly imprisoning 120,000 Japanese Americans and offered them $20,000 in reparations.

"The apology was even more important to our community for the majority than the actual token reparations," Ochi said.

But Ochi said her parents gladly accepted the reparations.

"It was so token compared to the three years of lost lives, businesses, opportunities, hopes and dreams," Ochi said. "I don't mind sharing that they were able to put a new roof on their house at that point and do things that people have to do and for which they didn't have a lot of extra money. As a good parents would, they give their children a small amount of that money."

After decades working as a teacher in Los Angeles, Ochi returned to Chula Vista to care for her ailing father. She now lives in what was her parents' home in Chula Vista. And, she's become more involved in the San Diego community again. That brings us back to the resolution the city council passed in 1942.

In 2021 the Japanese American Historical Society of San Diego collaborated with the San Diego Central Library on an exhibit about Clara Breed, the children's librarian at the San Diego Public Library when WWII began.

"(She) had befriended her students who came into the library. But not just befriended, she just helped them when they were forced to leave San Diego with their parents," Ochi said. "She was there at the train station to see them off. She gave them small gifts of postcards with postage. She maintained lifelong relationships with these Japanese Americans."

The work on the exhibit, which featured some of the 250 letters the children had written to Breed, led the modern day librarians to further research on what was happening in the city at the time and they discovered the resolution passed by the city council to support forcibly removing Japanese Americans from the city.

The five librarians who spearheaded the effort, Monnee Tong, Marc Chery, Steve Roman, Jennifer Jenkins and Sarah Hendy-Jackson, who Ochi called "librarian activists," also wrote a new resolution for the city rescinding the resolution from 1942.

It reads, “The Council of the City of San Diego apologizes to all people of Japanese ancestry for its past actions in support of the unjust exclusion, removal, and incarceration of Japanese Americas and residents of Japanese ancestry during World War II, and for its failure to support and defend the civil rights and civil liberties of these individuals during this period.”

The council voted unanimously in favor of passing the new resolution on Sept. 20. Each member present spoke about why they felt it was important.

"I do think it is our duty to use our platform to speak out against hate in any form," Councilmember Monica Montgomery Steppe, who is a member of the California Task Force to Study and Develop Reparation Proposals for African Americans, said.

During prepared remarks she made before the council on Sept. 20, Ochi quoted Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

"From 1942, when this resolution was passed, to today, 2022, it has been 80 years. It reminds me of the great civil rights leader, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., who often said, 'The moral arc of the universe is long but it bends toward justice.' And today’s council action is an important step in that same direction," she said.

More recently Ochi has been devoting time and energy to being an ally to members of the Black community exploring how the state can repair the harm to the descendants of enslaved U.S. persons. She's written letters and called the White House to ask the Biden Administration to issue an executive order to establish a federal reparations commission.

"The harms are really based on a very damaged system in this country of white supremacy and we really look to the constitution and their promises of justice for all," she said. "I think the time is right. I think now is the time that we really work hard for some repair to Black communities."