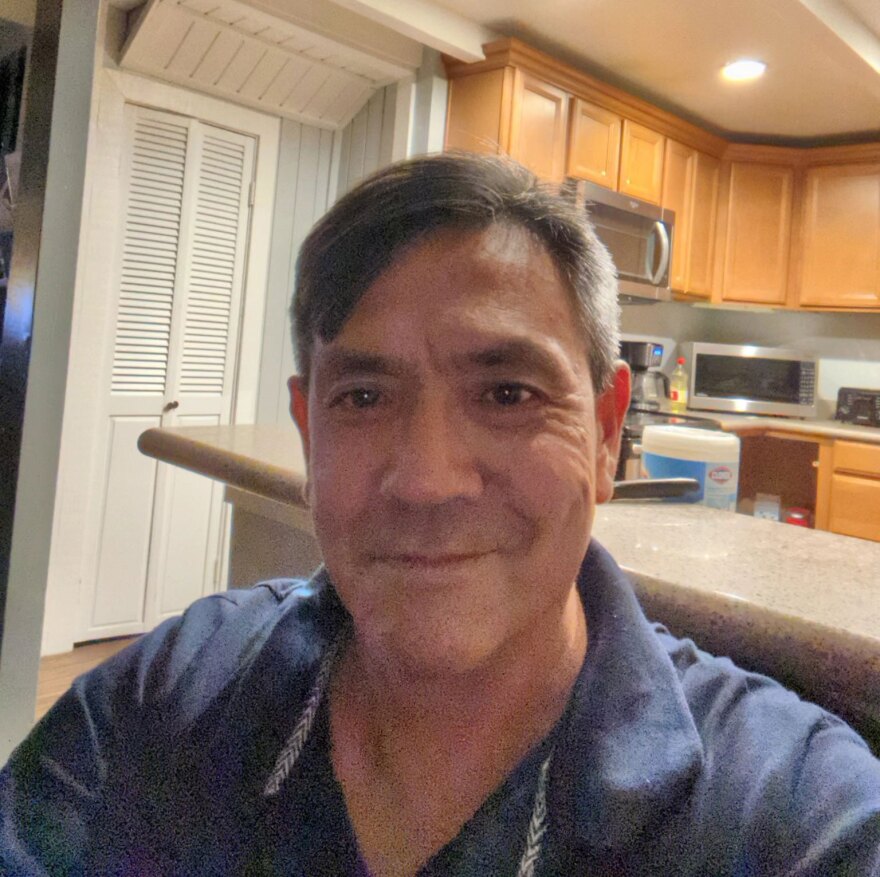

Frank Kensaku Saragosa never thought of himself as a writer. Even before addiction, homelessness and incarceration disrupted his life.

"I used to be a professor of American literature, and so I love reading. I love books, but I never thought of myself as a writer that way. I never thought I was a person who could write narrative," Saragosa said.

He'd struggled with addiction before — ultimately upending his career. He then worked in social services for a while, and that's when he began to understand the importance of stories. It almost drew him into a writing life.

Then he relapsed. In 2017, his drug use resulted in homelessness, and he lived on the streets of San Diego for the next few years until he was arrested.

'A Tale of Two Cities'

His nonfiction essay, "Caught Crossing, Caught Between — A Tale of Two Cities," chronicles the drug trade and homelessness on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border, and unflinchingly recounts his role in that world.

"In June of 2022, I was arrested for bringing 3.06 grams of crystal meth into the United States, and have been held in a federal detention facility ever since, " Saragosa writes in his prize-winning nonfiction essay, "The drugs were strapped to my body, hidden under my clothes, and I tried to walk through the San Ysidro Port of Entry from Tijuana, Mexico into San Diego county."

The border is tempting for unhoused individuals living in San Diego — particular during COVID-19. Lodging and food are far cheaper in Mexico, and for Saragosa and many of his peers, it soon led to recruitment as a drug mule.

Saragosa said it's the most vulnerable people — like homeless addicts — who are taken advantage of and ultimately punished in the crossborder drug trade.

"I knew that trying to bring drugs across the border, working for people, that was not a good idea, that I would end up in federal prison," he said. "I walked into it with my eyes open, but at the same time, it struck me — and this is the reason I wrote the essay — it struck me as really unfair."

"I walked into it with my eyes open, but at the same time, it struck me — and this is the reason I wrote the essay — it struck me as really unfair."Frank Kensaku Saragosa, author

'Life. In Pieces'

In prison, and in the full year he spent in pre-trial detention during COVID-19, Saragosa felt lost, adrift, and suffered with traumatic memories and troubling dreams.

"I had all these memories of living on the streets, of getting high all the time, of the psychosis that comes with that, and of all the things I had to do to keep getting high, and — it was just, they would come out in dreams, they would come out in memories that would just intrude at these strange moments. So I just began writing them down, kind of in a journal," Saragosa said.

"After a certain point, I decided that I really wanted these writings to find some kind of a life, because I realized that what I was writing about was a community of people and experiences of people that are really difficult, and that not many people write."

Those fragments became the work of fiction he entered into the PEN America Prison Writing Awards.

In "Life. In Pieces," Saragosa stitches together a patchwork of vivid, startling detail about different corners of San Diego alongside scenes and vignettes about other people, even about his childhood. In his writing, Saragosa's relationship with the city streets is powerful and palpable.

"Being unhoused, I lived a life that's out in the open and on the streets. And it's funny because when I was housed in San Diego, I would go to the restaurants on the same streets. I had friends who lived in condos and apartments on the same streets. So I would walk to work or to Petco Park or to wherever I was going and walk on the exact same streets that I walked on when I became homeless," Saragosa said.

His experience of those streets suddenly changed.

"They weren't just a way to get from point A to point B anymore. They became places where whole lives were lived, whole communities were formed, and all kinds of things went down. Transactions, commerce, relationships, all kinds of things."

While Saragosa didn't actively set out to write fiction — with invented characters and imagined scenarios — he didn't want to classify this piece of writing as nonfiction, even though it's his honest recollection from his memories and dreams.

"When you're unhoused and you're on the streets and you're high all the time — or at least when I was high all the time — there'd be days and days on end where I wouldn't sleep, and my life was in constant crisis and I wasn't eating regularly. So I can't trust my memory or my cognition under those circumstances," he said.

"All I can do is do my best to tell the truth, but then just acknowledge the fact that my work is just right at that place where fiction and nonfiction meet," Saragosa said.

"(The streets) weren't just a way to get from point A to point B anymore. They became places where whole lives were lived, whole communities were formed, and all kinds of things went down. Transactions, commerce, relationships..."Frank Kensaku Saragosa, author

Pandemic in the prisons

COVID-19 strained the already isolating state of incarceration — programs were canceled and any communal activities were shut down — libraries, classrooms, religious settings shuttered, Saragosa said. And no creative writing instructors were coming in.

Caits Meissner, director of prison and justice writing at PEN America, said that in some parts of the country, that's the reality — pandemic or not.

"The prisons and jails that have programs tend to be near cities," Meissner said. "But once you get into the woods where there sometimes are — like in Gatesville, Texas, six prisons on a strip of land and the whole town is making their money off of prison. They are what we call programming deserts."

For those programming deserts, their outreach and instruction programs rely on the mail, and PEN America hopes that a new grant-funded project will get copies of a new book, "The Sentences that Create Us: Crafting a Writer's Life in Prison" into prison libraries across the country.

But, Meissner adds, some "programming deserts" may stay that way.

"That's a whole other conversation about prison librarians, who's amenable, who's open, which prisons even have libraries," Meissner said.

When Saragosa heard about the Prison Writing Awards from a friend, he managed to get access to the computer terminals intended for preparing legal briefs, and typed up his fragmented memories into stories.

"The thing about being in prison is that you are cut off from society, and especially during COVID — 'cause I was locked up during COVID the entire time I was locked up. There were no visits," he said.

Writing became his outlet and way to seek connection. He knew that other people shared these experiences, and he knew that he wanted other people to see the realities of living on the streets, and learn to see homeless individuals as human beings.

"If I didn't have hope that I could write and possibly get published, then I would have no hope at all," Saragosa said.

The anthology, "Variations on an Undisclosed Location: 2022 Prison Writing Awards Anthology" will be published Dec. 2, 2022, including Saragosa's winning fiction and essay pieces, along with other writers' works of poetry, memoir and drama. Read more about the winners here.

Excerpt of 'Life. In Pieces' by Frank Kensaku Saragosa

I didn’t hit bottom. I hit The Bottoms.

That’s what I did. I left rehab and headed straight for The Bottoms.

They call it the East Village. That made me laugh at first. I lived in Manhattan and I know the East Village. This is not the East Village. I mean, it’s got that Space for Art, it’s got a cool performance space, it’s got cool new bars and restaurants, it’s got a gritty, industrial vibe. There’s a lot of new construction, but if you go far enough south and far enough east, to the very corner of downtown, right where the East Village hits Barrio Logan on the south and Golden Hill on the east, where Vinnie’s is (St. Vincent de Paul’s), and the Neil Good Day Center, and the Alpha Project tent—that’s San Diego’s skid row, it’s the heart of darkness, it’s where homeless people go to shoot up right on the street, out in the open, it’s where everything goes down, where whatever you’re looking for, black, or white, or rock, or powder, or roxies, or blues, or e, or china white that’s not really china white really it’s fentanyl, you can find it, right there, on the street, but not for strangers, you get hurt asking for shit like that people you don’t know don’t know you, if you do know, then you know where to go. It’s not dirty there, it’s grimy. But for people like me, it’s the place to go.

Homeless, sure. But place matters.