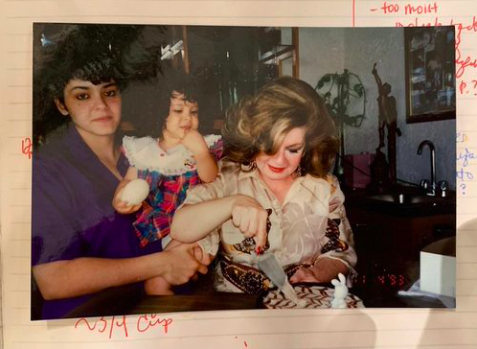

The first time round-brush bristles pulled at my wavy tresses, the heat of the hair dryer warming my scalp, my grandma hovered above me, working both tools together in perfect equilibrium. Her hair was a highlighted peroxide blond and always perfectly coiffed. Feathered and golden, her rounded layers were lifted at the root and coated in aerosol hairspray—a secondary fragrance—that held a scalloped silhouette with voluminous height in perfect place.

My grandma Mariana Cheney, or Tita as I called her, was the kind of person who would never be seen without her hair done, and only if I was awake early enough would I see her artfully crafting her makeup look of the day, always swiping a long cat eye over eyeshadow, painting on arched brown lines for eyebrows. Tita was the epitome of glamour, and her home in Guadalajara, Mexico, is where I remember her at peak elegance, sprawled in her bed wearing a beautiful robe, with makeup tools, eye shadows, liners, lipsticks, and single-set eyelashes splayed out in front of her. Luxurious and leisurely all at once, it was an aspirational sight—even when I was about six years old.

Tita and Tito moved around plenty, which meant I didn’t always have her nearby. For too long, she was more of a warm, recurring voice on the other end of a landline, so seeing her in the flesh was a special treat. That visit, I remember watching as she fixed up her hair one morning, blow-drying her bangs to refresh their roundness, the bathroom smelling like hairspray and hot, burnt hair. An idea swelled up quickly and softly erupted with the curiosity of a child.

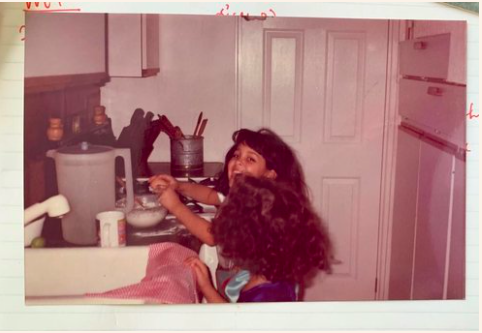

“Tita, me puedes alisar el pelo?” I asked in a small mousy voice. “Como Snow White?”

Like Snow White, I specified, wanting my bob to bounce and curve in at its ends.

She agreed, and soon enough I was sitting down in the bathroom, her round brush with the worn bristles holding her signature wiry blond strands now grasping my raven hair. The whirling sound of the hair dryer felt soothing, its monotone hum putting me in a calm, meditative state. Tita’s hands grasping my hair, racking her fingers through my scalp and brushing the length out vertically for oomph, comforted me, making me feel safe and loved. Like getting cariñitos.

I eagerly reached for the bottom strands of my hair, patting their newly smooth surface as Tita worked on the top, pulling and rounding my locks, the hair dryer’s music oscillating—getting nearer and further as the smell of burnt hair wafted through the room. When she finally finished, she sealed it with a cloud of hairspray, and I beamed to think that I smelled like her. Looking in the mirror, I had a small but momentous revelation: I felt pretty. I had exchanged my frizzy, shapeless, wavy mane for a smooth, rounded coif. I beamed at its sight, unable yet to articulate exactly why that was.

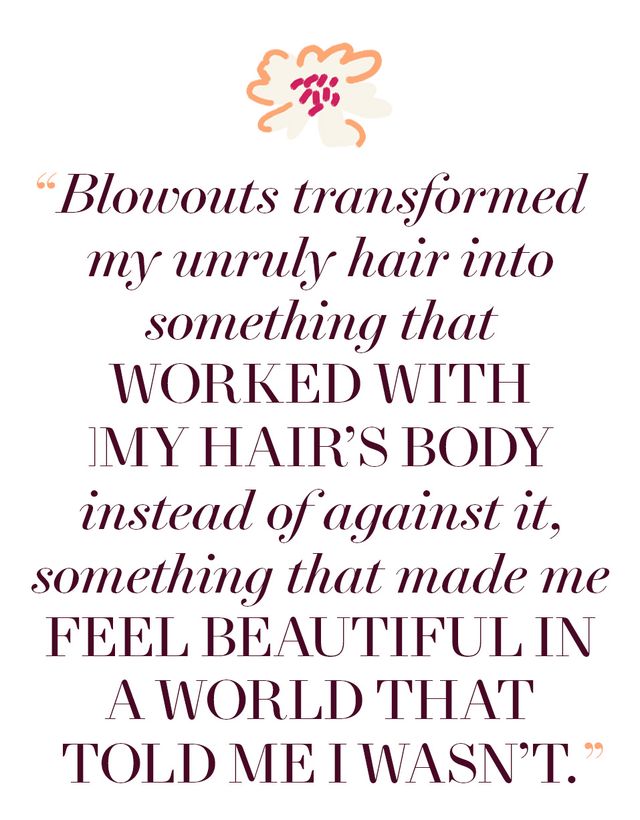

This would be the beginning of my love affair with hot tools and, moreover, blowouts. Even though throughout the years my methods would vary, from blowouts in the ’90s, to hot irons flattening my hair laid out on an ironing board in the early 2000s for my middle school years, to the flat irons I abused in high school as I went from emo to “indie,” blowouts were always a safe space. I’d get a blowout whenever I got a haircut or color job, giving my hair sheen and effortless bounce. It transformed my unruly hair into something that worked with my hair’s body instead of against it, something that made me feel beautiful in a world that told me I wasn’t.

After my first blowout with Tita, I began asking my mom for blowouts at home. I’d sit in my parents’ bathroom staring at my reflection, waiting patiently for the transformation as my mom pulled my hair up and away, rolling the round brush, waiting to feel pretty as she hovered above me with her long, tight raven ringlets. In that space between the sounds of the hair dryer and smell of my searing hair, when it was just her and me, I felt safe and cared for. It was something that continued over the years. I could always count on my mom to blow out my waves.

Even though having hair that made me feel connected to my matriarchs was a comforting experience with lustrous results, at some point another connection surfaced more strongly above it: Silky hair was the key to beauty. If my hair was smooth or straight or blown out, glossy or pressed in uniform curling-wand waves, the rest didn’t matter so much. My makeup could be minimal, I could have dark eye circles, my clothes could be baggy or scrubby—just as long as my mane was polished.

I realize now that the ideals that reject curly and wavy hair are a by-product of white beauty standards. Straight hair is good, and curly hair is not; this message has always been very clear. This idea was duly imprinted in me: My wavy hair was considered messy and uncouth, and I needed to tame it. When I was growing up, my nickname was Greñitas, which roughly translates to “shag” and implies your hair is unkempt. Upon setting his sights on my tresses, my dad would regularly ask if I planned on doing anything to the tangled nest on my head. Hair, and my appearance, for many reasons, was always at the forefront of my mind and apparently his too.

For so long, I was unable to accept my natural hair as “perfect as is.” At some point, the internal voice had adopted the criticisms of the external voice, even in its absence. It took me a long time to realize that generationally passed-down white beauty standards were to blame, though that wasn’t the only actor; media played a huge role too. In Mexico when I was a kid, watching telenovelas like Carita de àngel after school or looking at the magazine covers hanging on racks at the supermarket, whiteness and straight hair were always front and center. And if you weren’t that, then it was like you didn’t exist or like you weren’t supposed to.

Of course, so many of us with waves or curls were also styling our hair as if it were straight. Instead of working with it, we were fighting against its nature, creating a dry, shapeless, frizzy mop instead of hydrated and defined coiled tendrils. The education and resources simply weren’t there. Today, thankfully, finally, we live in the era of a curl revolution, and techniques like the Curly Girl Method have transformed how I approach my natural texture. I’ll admit, it’s not a happy ending quite yet, as I’m still working on embracing my natural voluminous and ungovernable texture with tons of hydration and inspiration from Tracee Ellis Ross and a certain fictional sex columnist, the ’90s Carrie Bradshaw. It’s a welcome process with occasional setbacks.

Suffice to say, my gifted Revlon hair-dryer brush definitely still revs its engine for my locks every once in a while and isn’t planning on retiring any time soon. But my curls are my mainstay.

As for Tita, blowouts had a grip on her appearance over the span of many decades. In fact, it wasn’t until she moved in with my mom and siblings after a series of devastations that I first saw her natural texture: tight ringlets similar to my mom’s. I wonder if life had conditioned her to scorn and hide her curls too. Or if our Mexican culture had simply ignored their existence.

When she came to us in our cramped apartment, life had taken almost everything from her, including the mobility in her dominant right side of her body. She was no longer herself. But crafty as ever, she didn’t give up on what made her feel like her, and she quickly taught her left hand to line her eyebrows and paint her classic black cat eye. But her tresses were the crowning jewel.

So I cut her hair and washed it, water uncovering hidden spirals. Standing above her, having switched places from all those years ago, I prepared to thermally bring back her signature coif.

“Como quieres tu pelo, Tita?” I asked how she wanted her hair as I held the blow dryer and round brush.

“Como Farrah Fawcett, chiquita.” Like Farrah Fawcett, she specified as she demonstrated the blowout pattern with her left hand, rounding her wrist. I smoothed her layered hair, flicking the bottom up and the rest of the layers rounded down and away from her face with volume at the root. Revealing a blowout that returned her to herself when she needed it the most.

This story was created as part of From Our Abuelas in partnership with Lexus. From Our Abuelas is a series running across Hearst Magazines to honor and preserve generations of wisdom within Latinx and Hispanic communities. Go to oprahdaily.com/fromourabuelas for the complete portfolio.

Andrea Aliseda is a Mexican-American writer and vegan recipe developer based in Los Angeles, CA. Her published work appears in Whetstone, Bon Appetit, Epicurious, and more. Follow her for updates on Instagram at @andrea__aliseda and Twitter at @alisedaandrea.