But in recent weeks, the outlet has been shaken by a major public-relations challenge. The uproar on social media and beyond has been fueled by the departure of four longtime hosts — Rodney Franks, Susan Gatschet, Matthew Goldwasser and Janine Santana — within the past six months, as well as the perception that the music mix at the signal, which has leaned heavily on the work of jazz giants, is being watered down in a revenue-driven quest for a younger audience.

The brain trust at KUVO, which merged with Rocky Mountain PBS in 2013 and currently has translators in Breckenridge and Vail, as well as hip-hop affiliate The Drop 104.7, is trying to control the damage by way of "community conversations" about the station, which is now based at the Buell Public Media Center, 2101 Arapahoe Street. The next gathering, accessible in person and online, is scheduled for tomorrow, September 28.

In advance of that meeting, Westword chatted with Franks, Goldwasser and Santana (Gatschet, whose association with KUVO began in 1996, was unavailable), who tell very personal stories about their exits, several of which coincided with family tragedies.

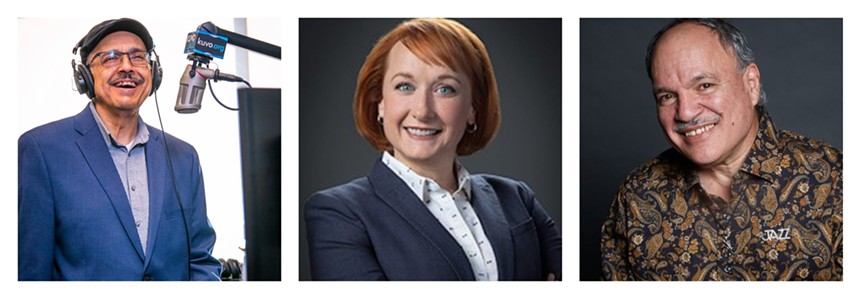

Westword also spoke with Carlos Lando, who is transitioning from his role as KUVO's general manager to focus on his signature program, The Morning Set With Carlos Lando; Rocky Mountain Public Media president and CEO Amanda Mountain; and KUVO music director Arturo Gómez. These three attempt to debunk what they consider to be misinformation about what's been going on at the station since new program director Max Ramirez joined the team in February — but they acknowledge shortfalls in communication that may have contributed to current concerns.

Along the way, KUVO administrators have contradicted assorted claims made by former employees and volunteers of the station — and vice versa. The resulting blend is very appropriate to jazz, which doesn't always take a conventional approach to harmony.

Let the music play:

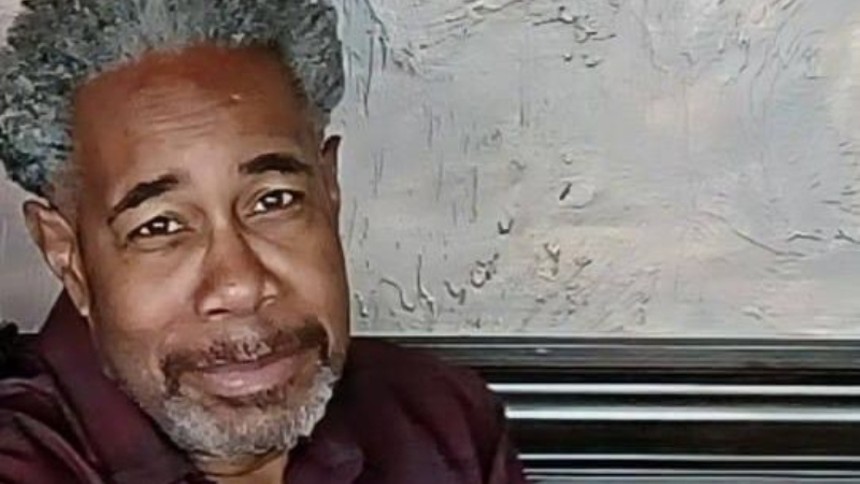

RODNEY FRANKS

"I find it really heartening that people have responded as they have," says Franks. "I do think their outrage is justified by the recent turn of events that have gone on at KUVO."

Franks came to the station "when I moved to Denver in 1991," he recalls. "That March, I started working as a volunteer at their old location on Federal Boulevard. Back then, I was working at other commercial stations, doing board operating and some other technical things with them. But I was hired as a full-time employee at KUVO in October 1995, and until earlier this year, I'd worked there on and off in various capacities. I worked the morning shift when Carlos wasn't available and just about every other shift at the station."

Over that span, Franks's indelible voice became closely associated with the KUVO sound, and he stresses that "I take infinite pride in the support the Denver community has given me through everything. Their pride in me really exceeds any recognition that I've gotten from the management of KUVO. Knowing that so many people were listening to me and supporting the station really kept me going."

That all changed on April 14. "I was called into the office on the pretext of an air-check review with Max," he says, "but when I got there, Carlos and Max were there, and Carlos said, 'This is your last day at KUVO.' He said, 'I don't like the mix of music you're playing,' and Max said my numbers weren't up to par."

That was news to Franks, who says it had been years since he'd been called into a huddle with higher-ups about the size of his audience — and the discussion then had been very different. "There was a period where Carlos only had me on for two hours a day, but the previous CEO saw my numbers, and saw they exceeded everyone else's. So Carlos was compelled to give me four hours a day," he says.

"Until Max showed up," he continues, "the determining factor for the success of a show was how much money we brought in for fundraising, and that was my wheelhouse. I learned a lot about that from watching Carlos do things; I have to give him credit for that. But Max told me he came from a station [WCIR in Indianapolis] that was chart-driven radio, which to me means you're editing songs and not playing the masters. And he had this ridiculous six-minute limit for songs. There were a few people upset about that, so he made it eight minutes. But that still eliminates a good portion of the jazz canon — like 'So What,' the Miles Davis song from the album Kind of Blue, which is over nine minutes."

The firing "blindsided" Franks, partly because it happened while he was still in mourning. "My father died on February 7 of this year, and if it wasn't for my dad, I wouldn't be doing this," he says. "I wouldn't know anything about jazz music. He was the one who inspired my love for jazz. It played in our house all the time when I was a kid." As the oldest child in the family, "I had to take care of everything after he died — execute the will, take care of his estate. And then I got fired, which I figured was just a one-off. But then my colleague, Susan Gatschet, lost her dad, and when she came back, they fired her, too. It makes me wonder if it was kind of like a sadistic pattern."

KUVO issued "a press release that implied I'd left on my own," Franks continues. "I told anyone I could that wasn't the case. I got a lot of correspondence from people saying, 'I'm sorry you're leaving KUVO,' and I would retort, 'I didn't leave anywhere. I was put out, and rather unceremoniously.'"

At present, Franks is busy working on an Internet radio project, but he retains a keen interest in KUVO: "I just hope it finds its compass again, because the captain is leaving a sinking ship."

MATTHEW GOLDWASSER

"For nine years, I was a volunteer at the station and an on-air host," says Goldwasser. "When I first started, I had a small segment on the morning show where I did film reviews. Then, after three years of development, they greenlit a show I had on Sundays called The Jazz River, which had a decidedly international flavor. I did that for three years."

The beginning of the end for Goldwasser was Franks's dismissal. "The internal document sent from the general manager, Carlos, was really whitewashed," he says. "It didn't refer to him as being fired; it just thanked him for his years of service and wished him well. And when Susan Gatschet was fired a few weeks ago, there was no statement at all."

But even before that, Goldwasser had concerns about other changes at the station. "The new program director, Max, sent out an email saying the daytime hosts could no longer play music that was longer than eight minutes, and that was followed by some other policy changes that restricted the creative freedom of the hosts," he recalls. "Like, 'We don't want you to play three of four songs in a row. We want you to play one and do some talking, and then play another one,' which wasn't really in the spirit of what the station was all about. And Carlos talked in a number of meetings about the importance of trying to bring in new music to recruit a younger listening audience. But if you look at the playlists they publish on their website, you can see they're not really following that."

He brought up these matters and more to Rocky Mountain PBS's Mountain, he says, but got nowhere "because I was a volunteer, and they think of volunteers as second-class citizens because they aren't paid staff or an outside consultant. ... I got into a spat with the social media person for what I felt was poor writing on her part in promoting my show and was suspended for two weeks. So I had two weeks to do penance and reflection, after which I decided I was just going to resign."

Six weeks later, Goldwasser posted on Facebook about his exit and those of Franks, Gatschet and Santana, and "it came as a complete shock to the listening audience, which had no idea these events had occurred," he says. "It definitely sent a ripple through the community."

And community is a key part of KUVO's original vision, Goldwasser points out: "Their mission statement is all about community, culture and music, and since I'm a mission-driven worker, I was really drawn to that, and I wanted to do everything in my power to contribute to it. And I did — I did everything from drywalling a hole in the men's bathroom to giving the station thousands of dollars to help meet its pledge drive. But ultimately, I felt like I wasn't respected or appreciated. And I'm a volunteer. I don't need that crap."

JANINE SANTANA

A New York native, Janine Santana came to radio through her career as a performer; she's a much-respected Latin percussionist. "I started at KUVO as a volunteer in 2009 or so and was hired on in the mid-2010s, probably," she recalls. "I was a paid employee for a long time, and I had the perfect shift."

Specifically, Santana hosted a show called Salsa Con Jazz, which celebrates Latin jazz. "I've worked as a musician for many years, and recorded and toured with some of the best. I didn't think I'd ever do radio, but I did it because Carlos asked me to," she says. "He's really been like a big brother to me in many ways — culturally, too, since we're both Puerto Rican — and he took me under his wing and helped me with everything. That's one of the reasons I was so disappointed that he wasn't responding to people and was going along with all the changes at the station. He said changes needed to happen and we needed to attract young people, but no one asked them what they wanted to hear. They just started programming new music or contemporary music, which was very confusing to me. He's like family to me — Arturo is, too — but he didn't seem to be standing up for the station except on behalf of the corporation that now oversees it."

When Ramirez took over as program director, she notes, "all this strange music started being injected. I worked as an actor in New York, so I know how to present things, I know how to talk about artists, but I just hated what I had to play. I thought, 'This is garbage.' I tried to infuse it with what I knew people were asking for, and when people would request things, I tried to play them. But I was told, 'Don't play that. This isn't the time to play that. It's too long, and we want more contemporary jazz,' which to me is smooth jazz, which isn't actual jazz. It's like pop music with a jazz flavor that doesn't have the depth of the real thing."

Santana also claims that "they're actually cutting down songs, too. They say, 'A lot of radio stations do this,' but my reaction is, 'Not ours.' People are paying to have the real music played. That's why they're contributing money. They say, 'If you play a twelve-minute song, people may turn it off' — and they will if it's not a good twelve-minute song. But now we can't play the Love Supreme suite [by John Coltrane]? Oh, my God. That is really scary."

Not that she found every suggested tweak objectionable. "We'd hear, 'Let's make sure we put some more fusion in it,' or 'Let's not play so many ballads,' or 'We need to include other formats of jazz,' and that was okay," she says. "I think most of us completely agreed with that. But when it started to be, 'You can't play classic tunes over this length because we don't have room in our new electronic library,' it was like, we're the ones who created this library, and we're the keepers of the culture. And then it became a real slash-and-burn thing."

Like Franks and Gatschet, Santana recently lost a parent: "My mother was passing away, and KUVO let me take a couple of weeks to help her. She ended up dying in my arms, and when I came back, it was difficult to know how to take care of things," she says. "But the station allowed me plenty of time to take care of things."

Before long, though, another health crisis loomed. "My son had a series of strokes and a really severe heart problem. He had to have emergency open-heart surgery, and it was really serious," Santana says. "I told them I needed a little more time, but then Max called and asked if I could please come in. He knew the situation with my son, so I thought it had to be something really serious. But what it turned out to be is that Rodney had gotten fired and they hadn't thought about who was going to do those shows. So they asked me to come from the bedside of my son, who I was afraid might be dying, because they didn't want dead air."

Santana's son survived, but he still required a great deal of care. And then, after she'd moved her schedule around to emcee the jazz stage at the Taste of Colorado earlier this month, she says: "I got an email saying, 'Your shift has changed.' They cut off most of my hours, which relieved me of all the benefits I had, including health insurance. And the hours they wanted me to work were in the morning hours, which is when I took care of my son. I told them, 'I'm available from twelve noon until the wee hours of the morning. You could stick me anytime in there. But the hours you're telling me are the only ones you want me to do are the only ones I can't do — and I'll lose all my benefits?'"

Shortly thereafter, Santana resigned — though she feels she was essentially forced to make the choice. Yet she emphasizes, "I'm not speaking about this out of animosity, KUVO has been my family. My son is very attached to KUVO; he grew up from babyhood with this station, and he loves everyone there. But now he thinks it's his fault I don't have a job. That isn't helping with his healing, and I'm really unhappy about it."

CARLOS LANDO, AMANDA MOUNTAIN AND ARTURO GÓMEZ

The last thing Carlos Lando wants anyone to think is that KUVO doesn't care about employees or volunteers who've suffered losses in their lives. He, too, experienced a recent tragedy — one he prefers not to detail. But long before that occurred, he says that the station went out of its way to offer employees "mental health days and bereavement days, which are all separate from sick days and vacation days. We go beyond what's required by federal and local levels. The timing just happened to be what was taking place with people at the time, but for us, it's all about family. And KUVO is a family."

At the same time, Lando says he believes the station can't simply stand still if it's going to survive and thrive over the long-term. "We are in a position of saying, 'Hey, we're here to serve our audience, but we're also here to evolve.' And what's happened over the course of this year has a lot to do with getting past the pandemic and getting back to serving our audience on a higher level," he says. "And there are a lot of things happening in radio, and especially public-media radio, that speaks to trying to address younger audiences. So part of this communication with our staff — and I've worked closely with Max on this — has to do with the changing face of the music."

A veteran of nearly twenty years at KUVO, music director Gómez is excited about many new jazz artists. Among those he name-checks are Catalyst, a funk/jazz quartet from Philadelphia; Boston's City of Four, which serves up funk along with jazz and fusion; acclaimed twenty-something jazz vocalist Samara Joy; and Argentinian saxophonist/composer Julieta Eugenio. But he also makes it clear that the outlet hasn't abandoned the greats of the genre.

"Our commitment to what everyone has always loved about KUVO is as strong as ever," Gómez says. "And we will always play the music of musicians from Denver and the Front Range and Colorado like no other station does. We will have them perform in our studios as we always have. Our commitment to them is embedded in us and will never change."

Gómez rejects the suggestion that KUVO has started editing tunes. "All songs are played as is," he says. "They may have an applause track edited out, because who wants to hear fifteen seconds of applause? But that's all. And there was never an edict to limit songs to six minutes. Eight minutes is more or less the margin for playing a song weekdays during the daytime, but evening and weekend hosts still have more time to play longer songs. During the week, it's been proven time and time again, regardless of the format, that people don't have the attention span they used to — but eight minutes is a guideline, and hosts can make an exception due to a passing or a birthday or anniversary of an artist."

Moreover, he insists: "We haven't added any smooth jazz during the day or the week. We have smooth or contemporary jazz at 8 p.m. Saturday night with The Dave Koz Show, but not during the day or during the week. That's when what we do is continue the history of jazz since its inception in the 1920s. But every ten or fifteen years, there's a change in the music for every generation, from New Orleans jazz to bebop to post-bop to many other kinds of jazz. And now we're adding the music of the 2020s."

The KUVO presentation won't mirror commercial stations with narrow playlists of material dominated by certain numbers played multiple times per day. "We're not going to have a rotation — not any more than we've had in the past," Lando says. "Trust me, I have always told people, 'I need you to include some vocals, some Latin jazz.' The only difference is that it will be a little more structured. But hosts will still have the choice of what they play from all these different genres, and the responsibility to listen to the music and select the best styles of jazz." To do otherwise "would be counterproductive to what people who love improvisational music want to hear and what KUVO is all about," he continues. "People tune in to the station because they want to hear new things, different things. They don't want to hear repetition. That's not going to happen."

Mountain isn't surprised by the strong reaction to KUVO's split with Franks, Gatschet, Goldwasser and Santana. "I think a lot of it is coming from this sense of loss our community has experienced over the past few years," she says. "There's such a closeness people have with hosts who may have been on the air for decades. So when changes are made, whether they leave on their own or the organization decides they need something different, there is loss."

The community conversations — they began for volunteers, hosts and staff in May, with the first open to the KUVO community at large debuting on September 20 — acknowledge such feelings, Mountain believes. "I think people who are really committed to being a part of KUVO are showing up and talking with us, and we're listening. And I feel they've been really respectful and productive. We're learning a lot about how KUVO got started, and that's giving us an opportunity to go back to our roots and build on our status as a community and cultural icon."

Mountain admits that some people "are interested in processing that loss in ways that are not always constructive. But I think overall, we're trying to keep in sight that our mission, our goal, is to really create a sense of welcome and belonging that so many people have found in KUVO and extend it to more people who don't even know KUVO is here for them — where they can help build it like generations of listeners before them. Our desire is to open up the conversation, not close it off, and that's a balancing act. But it's important to hear people who are in the tent while at the same time opening the tent up to invite more people in."

Social media posts attributed to onetime KUVO devotees who declare they've decided to stop donating to the station have been popping up regularly for weeks, but Mountain says the exodus has been more of a trickle than a flood. As of last week, only about ten of KUVO's 8,000 members have canceled their membership, she notes, and most of the others who are worried about the direction of the station "are open to talking to us, and we want to make sure those bridges stay open and clear and the conversations are good. Donors always have the right to give to what they feel most passionate about, and a lot of what people are passionate about is KUVO. We want it to be a welcoming place, and that may require a different lens — a sense of tolerance, a willingness to innovate together and apply community feedback. It's not just about fundraising. It's about how we can be more inclusive and welcoming, so it's not just for longtime listeners, but there's room for them to join this family that Carlos describes."

According to Lando, who will officially end his run as KUVO's general manager on October 31 (he'll remain an advisor): "One of my biggest regrets in all of this is that in our jazz community, there are a lot of people feeling angst and stress because they have a connection with hosts who did a wonderful job for so many years. That's a part of KUVO, and to deny that would be stupid. So I'm sorry all of this is happening, and even though there are certain things related to employment and human relations that tie our hands where we can't always speak to the moment, we need to do a better job of communicating with our community about what's going on. And we will."

Here's KUVO's summary of recent events:

ABOUT STAFFINGThe next KUVO community conversation will get underway at 6 p.m. on Wednesday, September 28, at the Buell Public Media Center, 2101 Arapahoe Street. Click to register for in-person attendance; capacity is limited. The meeting can also be viewed on KUVO's Facebook and YouTube pages.

• In the last seven months, KUVO has experienced 11 percent turnover of our on-air team, which translates to the loss of four volunteer and paid staff. Rodney Franks, Susan Gatschet, Matthew Goldwasser and Janine Santana are no longer with the station either because they decided to move on or the organization determined we needed something different for the future.

• Allen Scott and James Joyce (JJ), two long-time volunteer hosts, also had planned retirements in the one-plus year for personal reasons. (This brings our overall on-air turn-over rate to 17 percent over the last 24-plus months.)

• Our Monday-Thursday Jazz hosts have remained in place and have combined experience of over 100 years on the air at KUVO.

• The average tenure of our KUVO on-air hosts (volunteer and staff) is over fifteen years.

• In the next three-to-six months, we expect to add three new on-air hosts to our KUVO team and one additional radio engineer to beef up our technological support for in-studio and on-site community remote broadcasts.

ABOUT PROGRAMMING

• 98 percent of the KUVO programming schedule is the same. Two new programs have launched: Cruisin’ with Bella Scratch on Friday nights and Dave Koz on Saturday nights — and Brazilian Fantasy has gone from two hours to one hour on Sundays.

• Brazilian Fantasy will be going back to two hours on Sundays starting in January with enhanced marketing support

• KUVO is still considered a free form jazz format in large part because hosts still pick their own music tracks. Their selections are, however, moving into a format clock, which is a method of presenting the music intended to benefit the audience by increasing the variety of Jazz they hear.

• We are giving the station more structure and ease for the average jazz listener to tune in longer and on a more consistent basis. We are not moving to a light or smooth jazz format in any manner, other than where it has existed for the past ten years.

• KUVO has a massive music library of over 130,000 tracks and most of it doesn’t see the airwaves because they are in CD format, which is challenging to sort through on a daily basis. We’re in the process of digitizing our music library and for practical purposes, we need to refine the number of total tracks to a more manageable size. This process is being done methodically and is taking years to accomplish.

• Once we have our music library in a digital format, we can use new technology to serve our listeners at a higher level than ever before…developing a more consistent "KUVO sound" that is reflective of and evolving from community/audience feedback.

• Right now, we are playing more local and new Jazz artists than ever before.

• We are not, and will not, change the Jazz format of the station or sell the station to any other entity.