Boston archaeologists hope to find Underground Railroad relics in South End

The location, headquarters of the League of Women for Community Service, once hosted Coretta Scott King.

Boston’s archaeology team will soon begin a new dig in the South End, hoping to uncover relics tied to the Underground Railroad and other historical treasures.

The project is based at the headquarters of the League of Women for Community Service, located at 558 Massachusetts Ave. It will be the first dig in the neighborhood, according to the city’s archaeology program. A team will begin surveying the area Oct. 3 and is expected to continue working throughout the month.

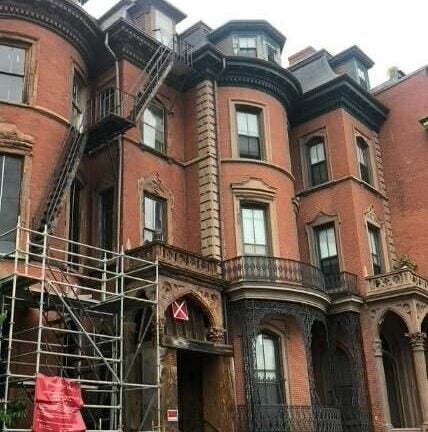

The building, a stately brick townhome, was built in 1858 for William and Martha Carnes and their three children, the city said. Situated on a former marsh, builders filled the site before erecting the home. The Carnes family profited from William’s furniture and fine wood importing business.

Today, the building has most of its original interior, and some original wooden furniture.

The property owners requested the dig, the department said, to possibly allow future development on the property. In particular, the League is working to fund a large-scale restoration of its headquarters. A $5 million capital campaign is underway.

The organization is dedicated to restoring the building, maintaining ownership of its collection of documents and artifacts, and expanding educational programming. The League has proposed making the building fully accessible by installing a wheelchair lift.

Archaeologists will work to determine what, if anything, can be recovered from the property to provide new information regarding the owners and occupants of the building throughout the decades. This includes searching for evidence linked to the property’s Underground Railroad history.

The Carnes family were “dedicated abolitionists,” the city’s archaeology program said, and oral tradition passed through the generations indicates their home was a stop on the Underground Railroad.

As wealthy Bostonians, the Carnes family had four indoor flushing toilets and two showers in their house decades before the rest of the city got reliable access to running water and sewers.

“I’m really curious to see what may be in the yard at this home, given that they likely didn’t have a privy,” said City Archaeologist Joe Bagley in a statement. “It’s possible that the hired help in the house had an outdoor toilet, but there should be a large cistern and cesspool somewhere on the property.”

Just 10 years after it was built, however, the Carnes family sold their home to Nathaniel and Eliza Farwell. Nathaniel was the mayor of Lewiston, Maine, and a cotton mill owner. Their daughter, Evelyn, married into the Ayer textile family.

“They were complicit in the cotton industry and benefited greatly from enslaved and later indentured labor in southern cotton plantations,” city archaeologists said.

The League purchased the building in 1920. Founded in 1918, the organization began as a group of Black women dedicated to supporting Black veterans returning from World War I. It was first known as the Soldiers’ Comfort Unit, according to the South End Historical Society. By organizing concerts, lectures, and exhibits, the group helped enrich Boston’s Black community.

Black people and immigrants flocked to the South End in the early 20th century, making it the most densely populated neighborhood of Boston by the end of the 1940s, city archaeologists said. The League hosted a soup kitchen, lunch program for children, and clothing swaps. The League set up the city’s first reading and game room in the basement for community members.

Many female Black students who were not welcomed in their colleges’ dormitories lived in rooms operated by the League during the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s. One of these residents was Coretta Scott, the future wife of Martin Luther King Jr. She stayed in the building while studying at the New England Conservatory of Music and during the early stages of her relationship with King, according to the League.

This archaeological work will focus on exploring the yard behind the building in coordination with members of the League and other community members.

The dig is open to the public, and updates will be provided by the city regularly through social media posts. A final report is expected to be published next year. Members of the public can volunteer to help by signing up for the program’s newsletter.

Bagley and his team are hard at work on another dig linked to Boston’s Black history. Earlier this month, a team began excavating at 42-44 Shirley St. to learn more about the nearby historic mansion known as the Shirley-Eustis House.

That residence dates back to 1747, and served as the seasonal country estate of William Shirley. First appointed by King George II as Royal Governor of the Massachusetts Bay colony, Shirley and his family lived publicly as the face of the British Empire. The mansion was likely moved, and archaeologists hope to uncover relics from its first location. This includes items tied to the enslaved people that Shirley and later residents owned.