19:30

Commentary

Commentary

Ever heard of ocean forests? They’re larger than the Amazon and more productive than we thought

Amazon, Borneo, Congo, Daintree. We know the names of many of the world’s largest or most famous rainforests. And many of us know about the world’s largest span of forests, the boreal forests stretching from Russia to Canada.

But how many of us could name an underwater forest? Hidden underwater are huge kelp and seaweed forests, stretching much further than we previously realised. Few are even named. But their lush canopies are home to huge numbers of marine species.

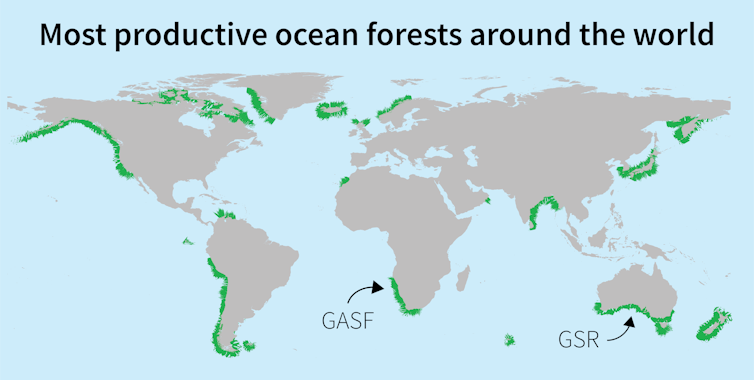

Off the coastline of southern Africa lies the Great African Seaforest, while Australia boasts the Great Southern Reef around its southern reaches. There are many more vast but unnamed underwater forests all over the world.

Our new research has discovered just how extensive and productive they are. The world’s ocean forests, we found, cover an area twice the size of India.

These seaweed forests face threats from marine heatwaves and climate change. But they may also hold part of the answer, with their ability to grow quickly and sequester carbon.

What are ocean forests?

Underwater forests are formed by seaweeds, which are types of algae. Like other plants, seaweeds grow by capturing the Sun’s energy and carbon dioxide through photosynthesis. The largest species grow tens of metres high, forming forest canopies that sway in a never-ending dance as swells move through. To swim through one is to see dappled light and shadow and a sense of constant movement.

Just like trees on land, these seaweeds offer habitat, food and shelter to a wide variety of marine organisms. Large species such as sea-bamboo and giant kelp have gas-filled structures that work like little balloons and help them create vast floating canopies. Other species relies on strong stems to stay upright and support their photosynthetic blades. Others again, like golden kelp on Australia’s Great Southern Reef, drape over seafloor.

How extensive are these forests and how fast do they grow?

Seaweeds have long been known to be among the fastest growing plants on the planet. But to date, it’s been very challenging to estimate how large an area their forests cover.

On land, you can now easily measure forests by satellite. Underwater, it’s much more complicated. Most satellites cannot take measurements at the depths where underwater forests are found.

To overcome this challenge, we relied on millions of underwater records from scientific literature, online repositories, local herbaria and citizen science initiatives.

Richard Shucksmith, Author provided

With this information, we modelled the global distribution of ocean forests, finding they cover between 6 million and 7.2 million square kilometres. That’s larger than the Amazon.

Next, we assessed how productive these ocean forests are – that is, how much they grow. Once again, there were no unified global records. We had to go through hundreds of individual experimental studies from across the globe where seaweed growth rates had been measured by scuba divers.

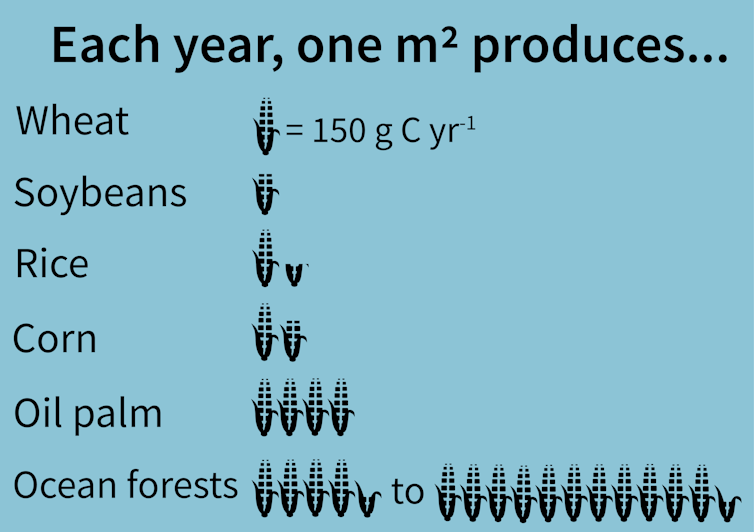

We found ocean forests are even more productive than many intensely farmed crops such as wheat, rice and corn. Productivity was highest in temperate regions, which are usually bathed in cool, nutrient-rich water. Every year, on average, ocean forests in these regions produce 2 to 11 times more biomass per area than these crops.

What do our findings mean for the challenges we face?

These findings are encouraging. We could harness this immense productivity to help meet the world’s future food security. Seaweed farms can supplement food production on land and boost sustainable development.

These fast growth rates also mean seaweeds are hungry for carbon dioxide. As they grow, they pull large quantities of carbon from seawater and the atmosphere. Globally, ocean forests may take up as much carbon as the Amazon.

This suggests they could play a role in mitigating climate change. However, not all that carbon may end up sequestered, as this requires seaweed carbon to be locked away from the atmosphere for relatively long periods of time. First estimates suggest that a sizeable proportion of seaweed could be sequestered in sediments or the deep sea. But exactly how much seaweed carbon ends up sequestered naturally is an area of intense research.

Hard times for ocean forests

Almost all of the extra heat trapped by the 2,400 gigatonnes of greenhouse gases we have emitted so far has gone into our oceans.

This means ocean forests are facing very difficult conditions. Large expanses of ocean forests have recently disappeared off Western Australia, eastern Canada and California, resulting in the loss of habitat and carbon sequestration potential.

Conversely, as sea ice melts and water temperatures warm, some Arctic regions are expected to see expansion of their ocean forests.

These overlooked forests play a crucial, largely unseen role off our coasts. The majority of the world’s underwater forests are unrecognised, unexplored and uncharted.

Without substantial efforts to improve our knowledge, it will not be possible to ensure their protection and conservation – let alone harness the full potential of the many opportunities they provide.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

GET THE MORNING HEADLINES DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX

Our stories may be republished online or in print under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. We ask that you edit only for style or to shorten, provide proper attribution and link to our website. AP and Getty images may not be republished. Please see our republishing guidelines for use of any other photos and graphics.

Albert Pessarrodona Silvestre

Karen Filbee-Dexter

Thomas Wernberg