The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

First Amendment Limits on State Laws Targeting Election Misinformation, Part II

An overview of state efforts to combat election misinformation.

This is part II in a series of posts discussing First Amendment Limits on State Laws Targeting Election Misinformation, 20 First Amend. L. Rev. 291 (2022). What follows is an excerpt from the article (minus the footnotes, which you will find in the full PDF).

Despite public outcry over the rise of misinformation in political campaigns, there is little federal regulation of the content of election-related speech. Other than in the context of campaign finance, federal law is largely absent in this space. Federal laws governing political speech focus primarily on advertising, but even with regard to advertising existing federal law is minimal and directed largely at traditional mediums of communication such as broadcast and print. Although federal agencies like the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) have "truth in advertising" laws that target false or misleading content in advertisements, those laws apply only to advertisements affecting "commerce," which the FTC has interpreted as precluding its ability to regulate the content of political advertisements.

The states, however, have not held back. Beginning in at least 1893, when Minnesota criminalized defamatory campaign speech, state legislatures have sought to enact statutes targeting false speech in elections. Today, forty-eight states and the District of Columbia have statutes that potentially regulate election-related speech, including but not limited to the content of political advertising. These statutes basically take one of two forms: statutes that directly target the content of election-related speech and generally applicable statutes that indirectly implicate election-related speech by prohibiting intimidation or fraud associated with an election.

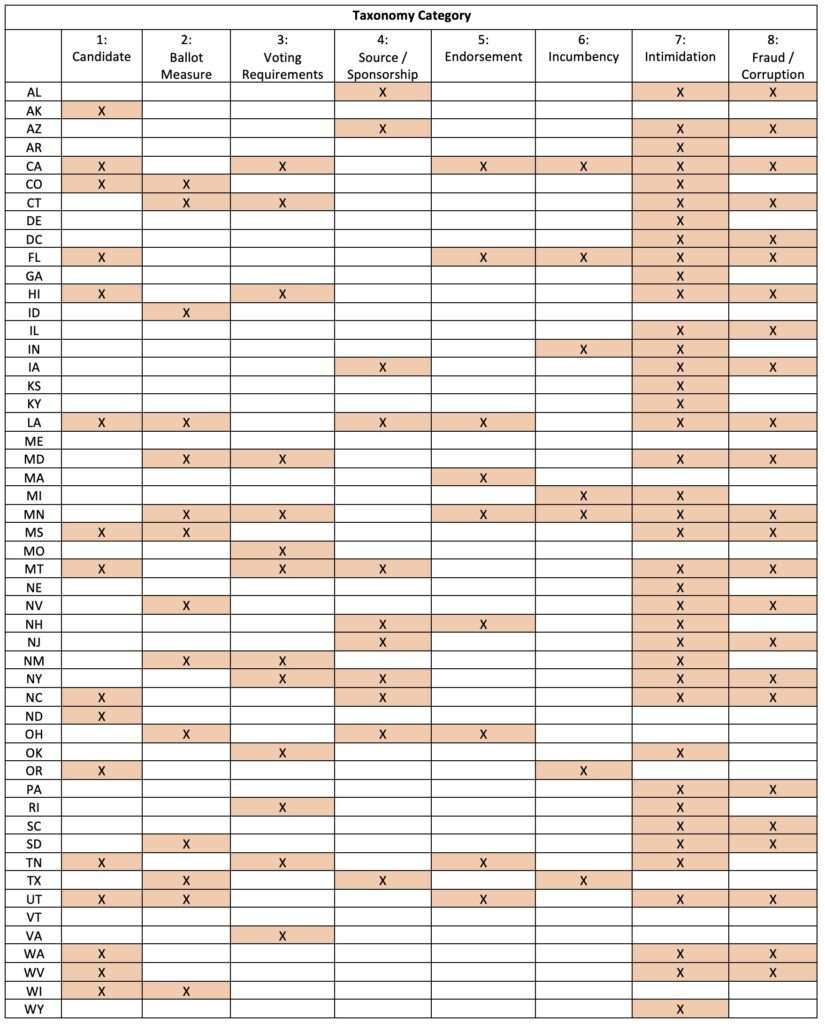

Before we examine the extent to which the First Amendment may limit state efforts to regulate election misinformation, it will be helpful to get an overview of the breadth and depth of current state laws that purport to address lies, misinformation, intimidation, and fraud in elections. To aid in this assessment, we developed a multi-level taxonomy of the types of speech targeted by the various state statutes. At the most general level, we can divide the statutes into eight categories based on the subject matter the statute regulates: speech about (1) candidates; (2) ballot measures; (3) voting requirements or procedures; (4) source, authorization or sponsorship of political advertisements; (5) endorsements; and (6) incumbency; as well speech that involves (7) intimidation; and (8) fraud or corruption. The top-level categories are not exclusive and many statutes fall within more than one category.

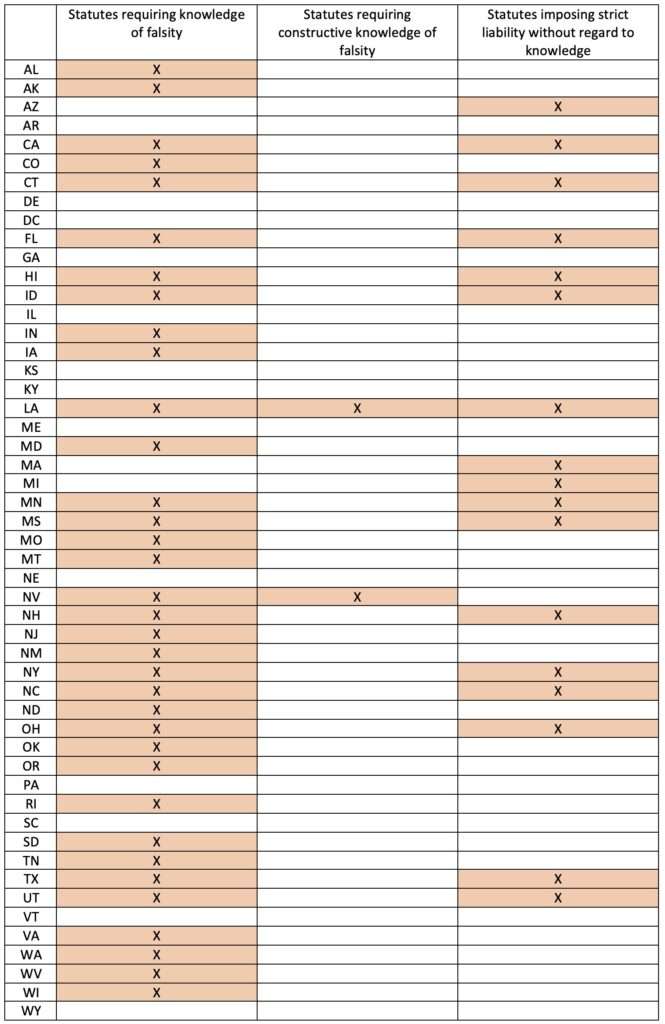

We also further divided each category based on the level of knowledge or intent, if any, the statute requires before liability attaches. For example, some statutes require that the false speech be made knowingly or with reckless disregard as to the truth of the statement. Other statutes impose liability if the speaker should have known the information was false, which is often referred to as "constructive knowledge." Still others impose liability regardless of knowledge, which is a form of "strict liability."

A. Laws that Target False Election-Related Speech

Statutes that directly target the content of election-related speech vary widely in the types of false speech they prohibit (note that most states have more than one type of statute):

- Sixteen states have statutes that prohibit false statements about a candidate for public office.

- Fourteen states have statutes that prohibit false statements about a ballot measure, proposal, referendum, or petition before the electorate.

- Thirteen states have statutes that prohibit false statements about voting requirements or procedures.

- Eleven states have statutes that prohibit false statements about the source, authorization, or sponsorship of a political advertisement or about a speaker's affiliation with an organization, candidate, or party.

- Nine states have statutes that prohibit false statements that a candidate, party, or ballot measure has the endorsement or support of a person or organization.

- Seven states have statutes that prohibit false statements about incumbency.

As this summary shows, the most common type of statute targeting the content of election-related speech prohibits false statements about candidates for public office. While a few of these statutes merely affirm that liability for defamation applies in the context of political speech, many statutes impose liability for false statements about a candidate regardless of whether the statement meets the specific requirements of defamation:

- Three states have statutes that affirm that defamation law (libel or slander) applies to political ads or campaign communications.

- Fifteen states have statutes that extend liability to any false statement about a candidate, even if it does not meet the requirements of defamation.

This highlights an important point about these statutes, as well as the other statutes that seek to limit election misinformation. In significant ways, election-speech statutes deviate from longstanding theories of liability for false speech. First, the statutes cover a broader range of speech than has traditionally been subject to government restriction: the statutes cover everything from merely derogatory statements about candidates (defamation requires false statements that create a degree of moral opprobrium) to false information about ballot measures, voting procedures, and incumbency. Apart from the liability created by these election-speech statutes, false statements regarding most of these topics would not otherwise put a speaker at risk of liability.

Second, a substantial number of statutes impose liability regardless of whether the speaker knew the information was false or acted negligently. In fact, the states varied considerably with regard to the requisite degree of fault required for liability:

- Thirty-three states have statutes that impose liability if the speaker knew at the time of publication that the information was false or acted with reckless disregard as to the truth.

- Two states have statutes that impose liability if the speaker should have known that the information was false, which is often referred to as "constructive knowledge."

- Seventeen states have statutes that impose liability regardless of whether the speaker knew or should have known of the statement's falsity, which is referred to as "strict liability."

[* * *]

[The following table shows which states have statutes that fall within the categories of fault described above. Note: States that only have statutes prohibiting intimidation or fraud associated with an election are not included in this table.]

B. Laws that Prohibit Intimidation or Fraud Associated with an Election

While the preceding laws directly target the content of election-related speech, a second set of state laws indirectly regulate election speech through the prohibition of intimidation or fraud associated with an election. Many of these laws were passed to prevent physical acts of voter intimidation. However, at least one state attorney general has used a voter intimidation statute to prosecute political operatives for the distribution of false statements relating to an election, suggesting that these laws could potentially apply to election-related speech more generally.

Thirty-eight states and the District of Columbia have laws that prohibit intimidation and/or fraud in elections (note that most states have more than one type of statute):

- Twenty-nine states have statutes that impose liability if the speaker made intimidating, threatening, or coercive statements with the purpose or intent of influencing or interfering with an election.

- Seventeen states and the District of Columbia have statutes that impose strict liability if the speaker made intimidating, threatening, or coercive statements that influence or interfere with an election, regardless of whether the individual actually intended to influence or interfere with an election.

- Seven states have statutes that prohibit statements that deceive, defraud, or bribe a person to vote, refrain from voting, sign a petition, register to vote, or choose who or what to vote for that the speaker knows to be false or corrupt.

- Fifteen states and the District of Columbia have statutes that impose liability for statements that deceive, defraud, or bribe a person to vote, refrain from voting, sign a petition, register to vote, or choose who or what to vote without any explicit mention that the speaker must know or have reason to know of the statement's falsity or corrupt nature.

As these descriptions show, the fraud and intimidation statutes conceivably cover a broad range of conduct and speech related to elections. And, like the statutes that target specific categories of false speech, they vary in the level of knowledge (and intent) required for a finding of liability.

[***]

[This table summarizes which states have statutes that fall into each of the taxonomy categories outlined above.]

To get the Volokh Conspiracy Daily e-mail, please sign up here.

Show Comments (51)