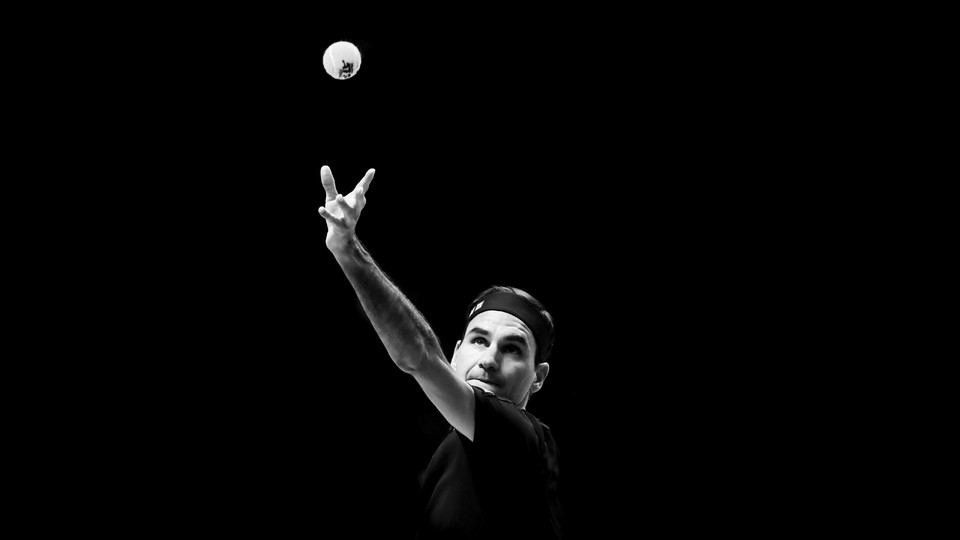

How Will We Remember Roger Federer?

Tennis is undergoing a dramatic change because even godlike players are proving to be human.

In the end, it was the knee.

Roger Federer has played more than 1,500 matches in 24 years, and has never quit in the middle of one for injury, illness, exhaustion, burnout, or apathy. His most formidable on-court opponents, Rafael Nadal and Novak Djokovic, who have surpassed him in Grand Slam count and are still battling it out for statistical GOAT status, cannot say the same. Nadal has retired (ended play) mid-match nine times, Djokovic thirteen. Federer’s joints––the ones that bore the stress of his game, birthed the transcendent nature of his movement––are the same ones finally forcing him to relent. His body simply can’t take it anymore, and there is nothing he can do to stop it. His legacy may be immortal; his physical condition is not.

On Thursday morning, an image of Federer––stately, smiling—appeared on Twitter with a voice narration of the same monogrammed letter he’d posted to Instagram. The upcoming Laver Cup, the tournament his agency helped debut in 2017, would be his final appearance. Twenty Grand Slam singles, and thousands of speculative guesses later, Federer’s retirement was official. It was long rumored, long expected, and somehow still felt like a shock.

The news might feel like less of a heartbreak if it were happening in a vacuum. Serena Williams announced her retirement from tennis in August. A frequently injured and 36-year-old Nadal’s decision feels imminent. Even Djokovic, a spry 35, is nearing the fifth decade of his life. We (us ’90s kids, in particular) are witnessing a very real changing of the guard. For 20 years, we were spoiled by an embarrassment of riches, some of the greatest athletes of all time, on court together, battling together––raucous, five-set duels, the kind that brought them to their knees, and screaming viewers to their feet. And now, what was changing slowly at first––humdrum wear and tear, a missed tournament or two––seems like it’s ending all at once. Suddenly, when we turn on our TV screens, we may see mere excellence, not historic aberration.

The congratulations, tributes, devastations, and crying emojis for Federer were both instant and global. The man is 41 years old––geriatric, in tennis years. He’d had three surgeries on his right knee in fewer than two years. In June of 2021, he withdrew after the third round of the French Open to preserve his precarious, twice-operated state and not risk further injury. That July, he lost in the quarterfinals of Wimbledon, as the oldest man since 1977 to play in them. Still, there was a hopeful sense that all of this—surgeries, rehab, absence, crutches—was somehow leading to a return, a Shakespearean call (“Once more unto the breach!”) to overcome the throes of pain. But there was one unspoken question: A return to what? To the smooth rotation of his preoperative knee? To his early 20s? (Could he take us with him?) He was always only going to get older. Still, the hope was a microcosm of the human relationship to physical form, especially in this era of technology and age reversal––a clinging to the idea that the body can revert to the state it was in before disease, age, injury, entropy come to call for it.

Federer himself may have held such expectations. He said, after his third right-knee surgery, that the worst was behind him, and that rehabilitation had, so far, been successful. One last go, perhaps on the grass of Wimbledon, where he’d won eight of his Grand Slam titles, was still on the table.

As it turns out, his 2019 Wimbledon match against Novak Djokovic was Federer’s last appearance in a Grand Slam final. He had two match points, on his serve—which, in tennis, is precisely the sort of offensive position you want to be in—and Djokovic saved them both. The loss was crushing. It felt like the first inkling of a physical decline. In 2016, he’d undergone arthroscopic surgery on his left knee to repair a torn meniscus (an unexpected result of running a bath for his children, he said, the day after losing to Djokovic in the Australian Open semis). He recovered in time to make it through to the quarterfinals of Wimbledon, but skipped the U.S. Open to give his knee a little more rest. In January, at the 2017 Australian Open, at age 35 years and 174 days, he won the title. He won it again in 2018, the second-oldest man ever to win a Slam.

There is something disruptive about the idea of tennis without the someone who’s become its synonym—the person who blazed in on the heels of Pete Sampras and Andre Agassi to build on their faster, topspin-heavy, whippier game, who metabolized it in such an irreplaceable way that sometimes watching it hurt. Federer upended expectations for what seemed possible with simultaneous grace and aggression. The Big 3—Federer, Nadal, and Djokovic—have won 63 of the past 77 Grand Slam tournaments. Early in his career, Federer played with bleached-out tips and baggier clothing, but the beauty of his game just became more of what it already was––the prima ballerina gliding on zero-gravity feet. His reflexes are second to none. His backhand is so beautiful that there is nothing new to say about it. He has a not-of-this-Earth quality about him, a thing that suggests the quotidian limits on the human body and mind can be challenged, tinkered with, chucked away altogether. Even in recent years, when he was playing in pain, passive observers were none the wiser.

The greatest rivalry in tennis may very well be that of the player versus the frailty of his parts. Consider the nag of Nadal’s foot, or Agassi’s back, or Andy Murray’s hip. In the early stages things can be staved off with localized injections, lidocaine, rest. A trim of the meniscus there, a reparation of the ligament here. Hips can be resurfaced, tendons reattached. But eventually, no matter the effort, or talent, or Slam count, the same outcome persists. The body is the thing, and degeneration is its victor.

On Monday, the 19-year-old Spanish tennis player Carlos Alcaraz stood in Times Square, holding his brand-new U.S. Open winner’s trophy above his head. The night before, in the men’s finals match against Casper Ruud, he’d won his first Grand Slam title and become the youngest man in ATP history to claim the No. 1 ranking. Alcaraz was born in 2003, the year that Federer won his first Slam. Federer’s retirement announcement came four days later. Alcaraz shared an image of the two together, grinning away, racquet in hand, as he stood next to an idol.