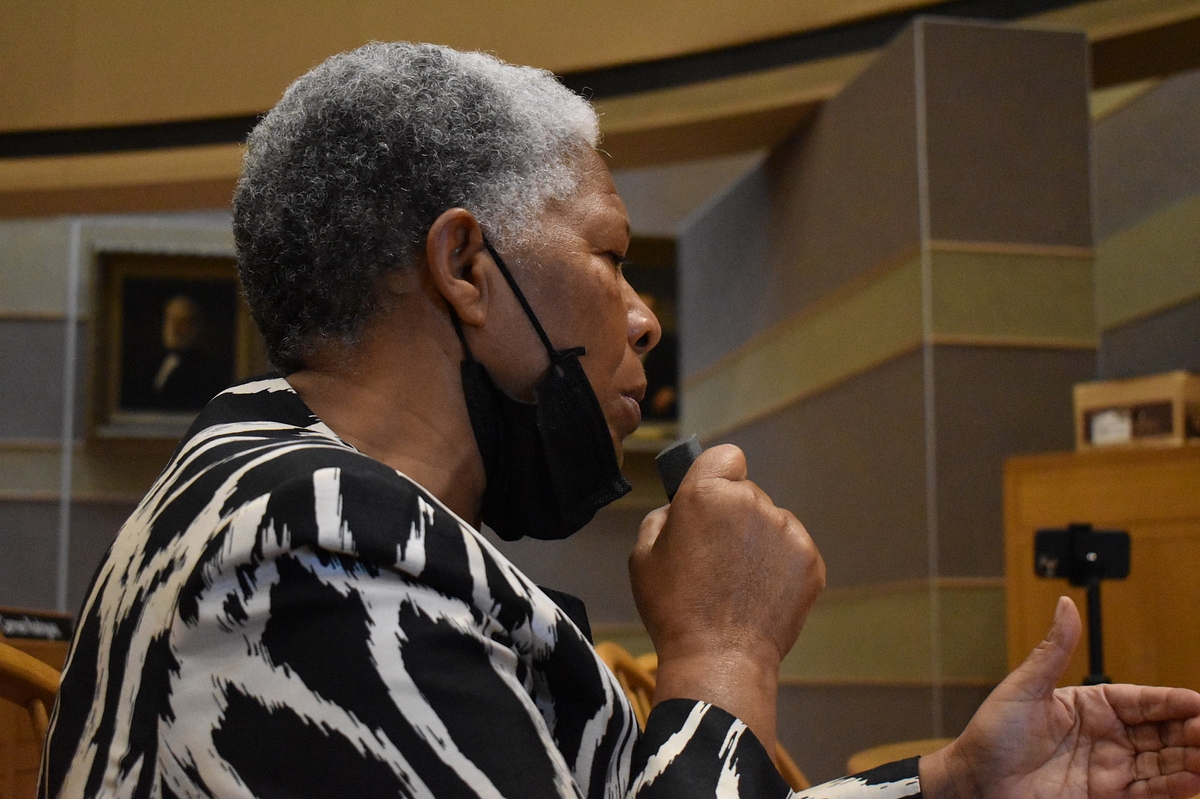

Laura Glesby Photo

Iline Tracey testifies: New Haven kids will succeed.

“When I hear those numbers, it makes me cringe,” Board of Alders President Tyisha Walker-Myers told Schools Superintendent Iline Tracey.

Speaking at a public hearing, she was referring to New Haven Public Schools’ test scores from the past year, which officials have referred to as a reading and math “crisis.”

“Our students are resilient,” Tracey responded, and they need “indestructible hope.”

That exchange unfolded at a Board of Alders’ Education Committee meeting, which convened at City Hall on Tuesday evening to hear a presentation from school leadership about student test scores.

The most recent scores revealed that of 8,000 third through eighth graders, 23 percent could read and write at their grade level, while 12 percent could do math at their level. (Read more about that end-of-year data here.)

Alders pressed school officials on their plans to ameliorate test scores over the course of the next year, while Tracey and other curriculum leaders maintained that the drops in scores reflected a predictable impact of the pandemic, poverty, and other sources of trauma on students’ ability to learn.

Meanwhile, teachers and paraprofessionals cautioned against over-testing students, arguing instead for a focus on the overall well-being of both children and staff.

Tracey insisted to alders that the test scores did not reflect a lack of effort or creativity among school leadership.

“We cannot negate the trauma of the past two years,” she said. “We were all trying to learn together.”

Tracey pointed to compounding effects of the pandemic, which resulted in over a year of online learning and isolation. Now 58 percent of students are considered chronically absent from school. “Teachers cannot teach empty seats,” Tracey said. And the students who do show up to school are acting out after a prolonged disruption to school routines. “The behavior was atrocious,” she said.

Teachers and paraprofessionals are also burned out, Tracey added. They deserve a raise that the school system is unable to afford, she said. As higher-paying suburban school districts are increasingly poaching educators from New Haven’s system, the teachers who remain here are stretched thin in understaffed schools.

“My poor teachers were so tired and burned out,” she said. “No one wanted to work in after-school programs.”

“I understand that the last two years have been difficult,” Walker-Myers responded. “But this is pressing. This is a priority.” She pointed out that New Haven schools were behind other districts in test scores before the pandemic began.

Tracey Tuesday evening responded that all of the state’s major cities, not just New Haven, have yielded lower test scores compared to suburban areas with access to more resources. That mirrors a racial and wealth disparity in test scores reflected within New Haven itself. (Click here to a read about a previous hearing held by the same committee at which alders heard from officials in other majority Black-and-brown cities who cited gains a result of switching form a “balanced literacy” to a more phonics-centered “structured literacy” approach.)

While test scores are low citywide in New Haven, Black and Latino children are especially likely to be below grade level. Among third through eighth graders, 19 percent of Black students and 20 percent of Latino students reached ELA grade levels, compared to 49 percent of white students and 41 percent of Asian students. In math, the disparities were even more stark: 7 percent of Black students and 8 percent of Latino students reached grade level scores in math compared to 34 percent of white students and 29 percent of Asian students.

Tracey noted that New Haven students are disproportionately struggling with housing and food insecurity, which affects their ability to learn.

She added that she does not want students in New Haven public schools to internalize a public sentiment that there is no hope for their academic achievement.

“I don’t want to enter the school year with that narrative for my children,” she said. She maintained that students are capable of bouncing back from a period of setbacks, even if it takes a long time. She returned to a refrain of “indestructible hope.”

Tyisha Walker-Myers: Time is running out.

Walker-Myers pushed back.

“I understand all of the barriers” facing New Haven students, she said. “But I’m not gonna feel guilty” about asking tough questions of the district. If schools do not effectively intervene, “ultimately, our kids will fail. … We don’t have a long time to catch up.”

Other alders chimed in with questions and suggestions.

Downtown/Yale Alder Alex Guzhnay urged Tracey to focus on challenging students for whom English is not their first language.

Fair Haven Alder Jose Crespo said he’s heard from some teachers that they do not feel comfortable voicing concerns and opinions about the curriculum. Tracey responded that “we do not have that culture,” but that discomfort may stem from a school-specific climate.

West Hills/West Rock Alder Honda Smith argued that “everyone needs extra money,” and that first the school system should demonstrate higher test scores — “then we can find extra money for the teachers.” (A handful of educators attending the meeting shook their heads.)

Committee Chair Eli Sabin pressed Tracey to share a detailed plan for improving academic achievement over the coming year.

“We do have a plan,” Tracey insisted. She said that schools would phase in a new reading curriculum, train educators in data-driven teaching and literacy techniques including phonics-based learning, build in more time for collaboration among educators, and phase in new math textbooks in middle and high schools. Academic improvement will be central office’s main objective, she said, whereas the last two years, leaders have been particularly prioritizing mental health and social-emotional learning.

Sabin requested more details about the literacy curriculum’s program design for a future meeting.

Teachers, Paras: Over-testing Harms Morale, Well-Being

Leslie Blatteau.

Hyclis Williams.

After Tracey and her team had a chance to present, teachers’ union President Leslie Blatteau and paraprofessionals’ union President Hyclis Williams shared an alternative vision for how schools should proceed.

They called for schools to prioritize mental health, morale, and school relationships among both students and staff over test scores.

“My teachers will know our students are behind,” said Blatteau. “Over-testing is not giving teachers the time and space to do our jobs.” While Blatteau said she believes some degree of assessment is important, too much of a focus on testing eats away at important teaching time, demands additional hours of data entry from educators, and lowers students’ motivation to come to school in the first place.

“We’re looking beyond just the test scores from one day,” added Blatteau, who called on school leaders to incorporate data on how students “reflect on their progress” and “present and advocate for their needs.”

Blatteau and Williams also echoed Tracey’s call for higher teacher and paraprofessional salaries.

Williams said that paraprofessionals’ responsibilities have been growing amid staff shortages, despite their notoriously low salaries. Paraprofessionals’ 2022 – 2023 salaries range from $23,397 to $45,055, per their contract. Many paras are living in poverty and turning to resources like soup kitchens. Their precarious financial situations are affecting their ability to be present at work, Williams said. “It is a mental health thing, too.”

Blatteau spoke of a similar low morale among teachers. “It feels like every month, a new thing is added to our plates. Things are not getting taken off our plates. Our salaries are not keeping up,” said Blatteau. A survey of teachers’ union members found that 22 percent of the 1,000 responding teachers are planning to look for jobs at higher-paying districts.

The pair also called for paras’ and teachers’ voices to be included in school-wide decisions by revitalizing the Comer school model of collaborative school management teams, which have historically included educators and other staff, parents, and students in policy decisions. Paras in particular are often left out of school decisions, Williams said.

Finally, the pair spoke to a vision of schools as hubs of intergenerational community and support. Blatteau pointed to the “community school” model that some cities like New York have adopted, with mixed results; community schools provide wraparound services and afterschool programming to kids and families after instruction hours, focusing on the “whole child” rather than primarily on academics.

Alders could help by advocating for fewer testing requirements attached to state grants, they said, and by connecting community members to schools.

“I don’t think many people who haven’t been to school these past two years know what our classrooms look like,” Blatteau said. “Our students are telling us they are struggling. We need trusted community folks to wrap their arms around our kids who are struggling.”

Tracey Details Reading Argument

Earlier on Tuesday, Tracey addressed the specifics of the reading controversy during an interview on WNHH FM’s “K Pasa” program. (Watch the interview above; it is in both Spanish and English.)

Tracey said it’s true that NHPS is still using a balanced literacy program. But she asserted that “much of the coverage and conversation about the teaching of reading has been misdescribed.” NHPS is not “against” any one approach, she said; it incorporates phonics in its balanced literacy curriculm.

“Everyone who listens to me and my team has heard me to say, ‘No one size fits all.’ We don’t teach programs. We teach students. Programs don’t teach anyone anything. You have to have the people who are implementing any program have to still be trained in the nuances of those programs,” Tracey told program host Norma Rodriguez-Reyes.

Tracey noted that the national debate about how to improve the teaching of reading dates back to the time of Horace Mann, “the father of public education” in the 19th century, through the “Johnny Can’t Read” debate in the 1960s, the “A Nation At Risk” report in 1984, followed by “No Child Left Behind.”

The challenge, she argued, “requires us to understand where students are, to diagnose their needs, and whoever the students are, mediate the needs of the students. We can’t be so tunnel-visioned that we are gung ho on one approach or another approach. …

“Not all students are auditory learners. Some students are more kinesthetic. Some are more visual. Some are more tactile; they have to touch and learn things. We have to bring all these things to bear on the teaching.”

Critics of balanced literacy argue that decades of brain research show that it can set children back to teach them to identify words based on pictures or how the whole word looks rather than to sound out the component parts.

Paul Bass contributed to this story.

Paraprofessionals’ 2022 – 2023 salaries range from $23,397 to $45,055, per their contract.

Are the teachers' aides salaried or hourly employees? Are they paid a fixed rate for each hour worked, rather than an annual salary regardless of time worked?