Many of the Taliban freed under the Doha Agreement took up arms, providing a deadly illustration of how the US-Taliban deal undermined the viability of the Afghan republic.

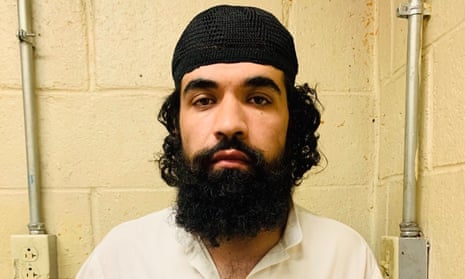

Hekmatullah, a Taliban infiltrator serving as a sergeant in the Afghan National Army, was involved in a so-called “green on blue” turncoat attack that killed three Australian soldiers in Uruzgan in 2012.

He was arrested and sentenced to be executed by the Afghan justice system, but the bargain struck by the US and the Taliban for the release of thousands of such convicts led to his transfer to Qatar in September 2020, and he was subsequently released in October before the militants subsequently overran Kabul on 15 August 2021. He returned to Afghanistan after the collapse of the government.

I was involved in the Afghan government’s ultimately failed efforts to prevent his release.

A week before the release of thousands of Taliban convicts started as per the Doha Agreement, Afghanistan’s Office of the National Security Council (ONSC) alerted the former president to Australia’s request for “urgent intervention” to prevent the release of Hekmatullah as part of the Taliban’s wishlist seeking the release of 5,000 of its fighters.

The Afghan government assured Australia that it would do all it could to prevent the release of the convict of concern.

Among the assurances provided, was that Hekmatullah had committed what under Islamic law would be crimes that the state cannot pardon, so legally he could not be released under Ghani’s decree authorising the release of certain categories of Taliban convicts.

While the government did not have direct contact with the Taliban at that point, opposition to Hekmatullah’s release was communicated to the US, which was playing the role of intermediary and shared the position with the Taliban.

The US had its own concerns with the Taliban’s list.

On 18 April 2020, the US provided the Afghan government the names of more than 200 convicts with a request that their release be delayed until the end of the process. Among them were Hekmatullah and three convicts of concern to Norway. Some among the 200 were Taliban infiltrators that had killed US soldiers in green on blue attacks.

But on 30 April, the Taliban sent the government, via the US, a list of 90 convicts with a demand that they replace existing people. The Afghan government was expecting that the US had managed to convince the Taliban to replace the convicts of concern with others. But the Taliban’s new list did not replace Hekmatullah or any of the others whose release was objectionable.

The Afghan government withheld the release of these convicts of concern.

But as time dragged on, the US communicated to the Afghan government increasingly stringent Taliban demands: Peace negotiations would not start until all the 5,000 Taliban convicts were released, even though the US had previously assured the government that the deal’s language of “up to 5,000” meant the US negotiators would convince the Taliban to start the talks after a smaller number was released.

Not only that, the Taliban also insisted that exactly the same 5,000 convicts be released that it had named in its list, a demand that the US admitted to the Afghan government went beyond the letter of its deal with the Taliban – the agreement was on numbers, not individual convicts.

Despite the US assurances to the Afghan government that it was working to convince the Taliban to be flexible, the group never budged.

The inability of the US to influence the Taliban was matched by its continued insistence that the Afghan government continue the releases.

The Afghan government’s reluctance to release hardened terrorists meant that the clock was ticking on the 14-month US withdrawal commitment – which the government did not oppose – and other interrelated provisions of the deal. It also gave the Taliban a pretence to cast the government as an obstacle to peace.

Meanwhile, the Taliban’s violence escalated. A campaign of attacks against religious clerics, hospitals, journalists and others associated with the government was in full swing when, in June, a group of prosecutors working to move forward the release of the Taliban convicts was killed in a targeted attack. They had been doing difficult work at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, at great risk to themselves and their families, in order to advance the cause of peace.

Quick GuideHow to get the latest news from Guardian Australia

Show

Email: sign up for our daily morning and afternoon email newsletters

App: download our free app and never miss the biggest stories

Social: follow us on YouTube, TikTok, Instagram, Facebook or Twitter

Podcast: listen to our daily episodes on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or search "Full Story" in your favourite app

The government suspended releases in response but came under immediate pressure to resume because the US remained deeply invested in ensuring that the commitments it made to the Taliban under the deal were fulfilled.

By August, nearly all the 5,000 convicts except six had been released.

The six included Hekmatullah and other convicts of concern to France and the US. The Afghan government, through the US, offered the Taliban to release any other six convicts instead, but the US failed to secure the Taliban’s agreement.

Both France and Australia were also separately engaging the Trump administration to stop the release of the convicts.

But in early September, the US informed the Afghan government that it had managed to convince France to withdraw its objections to the release of three convicts, an outcome favourable to the Taliban.

When the Afghan government shared this with the French embassy in Kabul, the French diplomats consulted with Paris and denied that such an agreement had taken place.

The US-Taliban deal was “behind schedule” on many of the key deliverables, the most important of which to Afghanistan was peace negotiations, which had been delayed since the date of 10 March 2020 agreed by the US and Taliban.

A consensus emerged among the US, the Taliban, the Afghan government and Qatar on 3 September to send the six to Qatar under house arrest “until at least 30 November”, according to a text outlining the agreement.

Just prior to the late-night transfer flight on 6 September, my office was evaluating possible reactions from Australia.

Australian bilateral efforts to prevent Hekmatullah’s release had been so vigorous that possible responses envisioned by the government included temporary recall of its ambassador and a cut in development and security assistance.

The Australian response turned out to be more measured.

Hekmatullah remained a priority for Australia and the families of the Australian victims.

My office briefly considered arranging for a bilateral treaty to give Australia custody of Hekmatullah so he could serve out the rest of his sentence, but it was abandoned for technical and political difficulties and the idea was never shared with Australia.

After the 30 November deadline expired the government sought to extend the house arrest of the six convicts for another six months. In trying to explain the difficult choices that Afghanistan had to make, I told an interlocutor “many of the 5,000 convicts were involved in the killing of Afghan citizens and soldiers, and citizens and soldiers of our partner nations who were in Afghanistan to help us rebuild and rehabilitate”.

It was the same message the Afghan government conveyed to Australia and France.

It is also the sentiment I carry as I reflect on the severe limits placed on the menu of Afghanistan’s policy choices as demands of law, diplomacy, peace and security exerted competing pressures. With the benefit of hindsight, better choices might have been made, but governments rarely have both the luxury of context and liberty of action.

In the end, Norway and the US quietly dropped their objections to the release of Taliban fighters convicted of killing their citizens. But most of the convicts had been involved in attacks against the Afghan people and state. Many of them took up arms again upon release, providing a deadly illustration of how the US-Taliban deal undermined the viability of the Afghan republic.