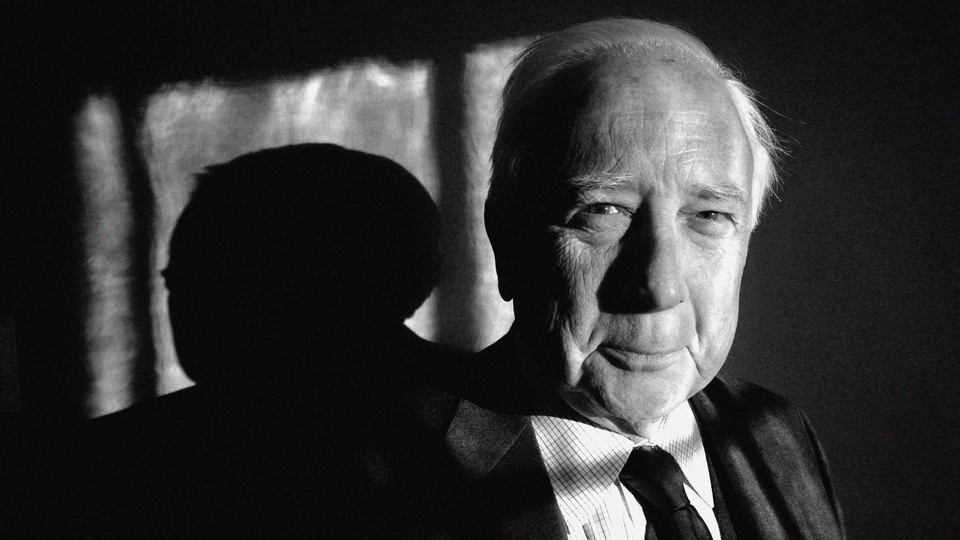

‘History Is Human’: Remembering David McCullough

With the death this week of David McCullough, we lost an author who understood how to find the stories that made history feel relevant and real.

Two years ago, I happened to come across an interview with David McCullough in the Vineyard Gazette, his hometown newspaper. I still have it, printed out and placed in a folder in my desk drawer. I kept it because, as was so often the case, McCullough had said something that I wanted to remember. “There are any number of ways to begin a book,” he had told the interviewer while they sat on the back porch of his house on Martha’s Vineyard. “I like to begin with somebody on the move.”

The first book I read by McCullough was John Adams, one of his many masterworks that begins with men on the move. “In the cold, nearly colorless light of a New England winter,” he wrote, “two men on horseback traveled the coast road below Boston, heading north.” For me, that was all it took. I wanted to know who these men were, where they were going, what was going to happen next. I did not care that the book was nearly 800 pages long. I was hooked.

For writers of nonfiction, there are subjects, and then there are stories. McCullough always told stories. In 2003, in an electrifying speech titled “The Course of Human Events,” which he gave for the Jefferson Lecture in the Humanities, McCullough famously said that “no harm’s done to history by making it something someone would want to read.” History, he believed, was for everyone. It affected us all, so it belonged to us all. It could begin or prevent wars; expand or distort human understanding; connect us to other cultures, other times, other species. It was important, but that did not mean that we had to grit our teeth and set out on a forced march through the past. On the contrary, we should be sucked in from the first page.

McCullough’s books, his hundreds of interviews and articles, his words of wisdom to struggling writers, the irresistible stories he told his legions of loyal readers, left an indelible mark on my own writing, and I am far from alone. Since the publication of his first book, The Johnstown Flood, in 1968, when he was 35 years old, narrative nonfiction, as it has come to be known, has grown exponentially, giving rise to such accomplished and dazzling writers of biography and history as Erik Larson and Laura Hillenbrand, Isabel Wilkerson and David Grann. Those of us who admire these authors have, in many ways, McCullough to thank for their riveting work. He opened a door and they walked through, carrying us along.

For most of his life, McCullough wrote in a small, book-lined backyard shed, which he called “the bookshop.” “Nothing good was ever written in a large room,” he argued in a 1999 interview with The Paris Review. Inside the bookshop, on a small desk, sits a green banker’s lamp above a Royal typewriter, which he bought for $25 in 1965. “When I was setting out to write my first book, I thought, ‘This is going to be business, McCullough. You ought to have one of these at home,’” he said. “Everything that I’ve ever written, I’ve written on that typewriter … And after a while, I began to think, maybe it’s writing the books. So I didn’t dare switch.”

As loyal as he was to his typewriter, McCullough was exacting when it came to his subjects. He did not have to love them, but he did have to be able to live with them. “It’s like picking a roommate,” he said, explaining why he had decided not to write a biography of Pablo Picasso, even though he himself loved to paint. “After all you’re going to be with that person every day, maybe for years, and why subject yourself to someone you have no respect for or outright don’t like?”

The many books that did survive McCullough’s careful review, pounded out on his trusty typewriter, told wide-ranging deeply human stories that inspired a new generation of writers. He mesmerized us with tales of the astonishingly brave and slightly insane men who built the Brooklyn Bridge and the bicycle-selling brothers who found first flight. We studied his young Theodore Roosevelt, born into aristocracy, galloping into history, and marveled at the incredibly crowded and complicated presidency of Harry S. Truman, a quiet, piano-playing haberdasher from Independence, Missouri. “History is human,” McCullough said. “It’s about everything. It’s about education. It’s about medicine. It’s about science. It’s about art and music and literature, and the theater. And to leave [all that] out is not only to leave out a lot of the juice and the fun and the uplifting powers of human expression, but it is to misunderstand what it is.”

From David McCullough we learned that it is never enough to simply describe the past. To read one of his books is not just to understand the people who populate its pages, but to feel like you know them. As a reader, the only way to achieve that kind of intimacy is to find a writer like McCullough, whose own fascination with his subjects is palpable in every word he wrote. Unfortunately, there is no other writer like McCullough. We have lost one of the greats, but how lucky we were to have learned from him, and to know that, every time we reach for one of his books, we are setting off on an adventure. Be ready to hit the ground running, because somebody’s going to be on the move.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.