Over the past decade, California has been making incremental progress toward reducing suspensions and expulsions — which are disproportionately used to punish students of color, low income kids, and kids with disabilities — and replacing reliance on school discipline with restorative justice practices.

That progress appears to be stalling, and in some ways, reversing, according to a new report from the Center for Civil Rights Remedies at the UCLA Civil Rights Project.

On the surface, data collected during the 2019-2020 school year showed suspension rates were continuing a slow decline.

Yet, California students only completed 70 percent of the 2019-2020 school year in-person before coronavirus closures arrived in March 2020.

When UCLA researchers adjusted suspension rates to account for the final three months of school in which schools did not dole out suspensions at all, they found that positive-seeming school discipline numbers from that year were frequently the result of under-reporting.

The researchers found that school districts that gave out more suspensions by March 2020 than they had in the whole previous school year did not set off warning bells in the state’s monitoring system.

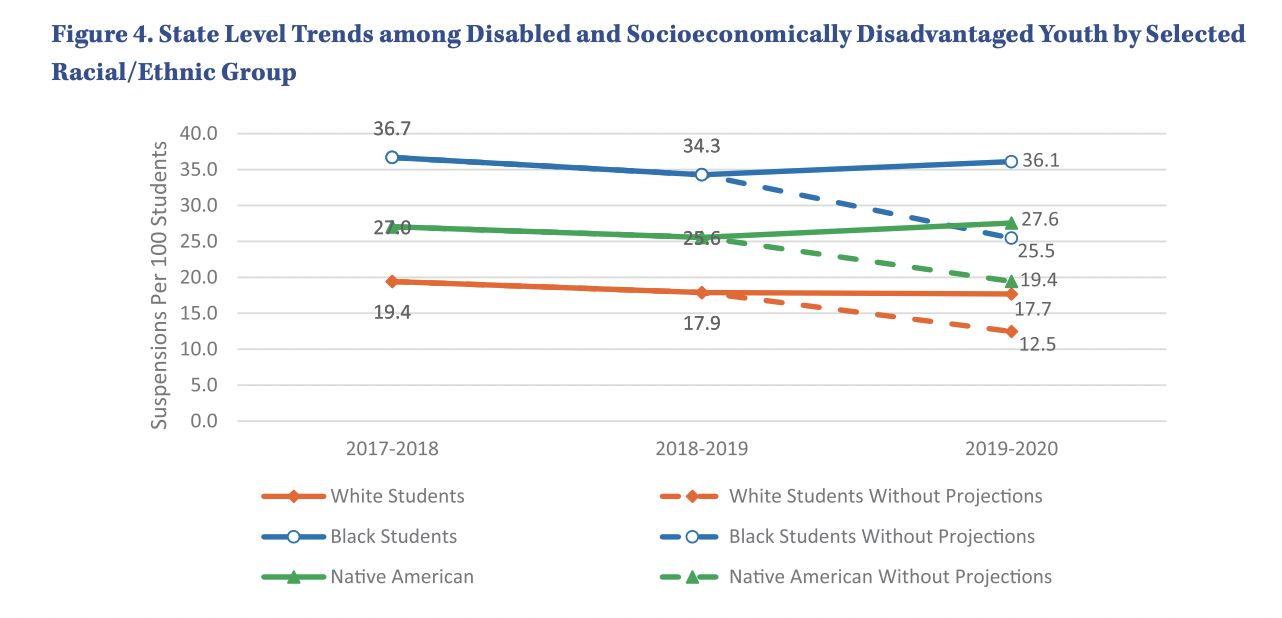

Statewide, low income students with disabilities, especially those who were Black or Native American, would likely have experienced higher rates of suspension than during the 2018-2019 school year, had they finished out the rest of the school year in 2020.

This is especially disheartening considering that while suspensions were dropping across the board earlier in the 2010s, racial disparities in school discipline remained a serious problem, especially for Black boys who were unhoused or in foster care.

Now, rising suspension rates pose an even bigger problem for students who have already missed out on classroom time because of the pandemic.

“Students lost a great deal of instruction time after schools halted in-person instruction in March 2020 in response to COVID-19, and many students are already behind where they would normally be academically,” the researchers wrote. “The groups of students who were disproportionately harmed by COVID-19 are the same students who tend to be suspended disproportionately.” It’s critical that students get as much instruction time as possible. “With so much instruction time already lost, further removals from instruction as a response to misconduct could be even more harmful than before.”

Researchers also analyzed data on the interactions between law enforcement and students.

The share of Black students stopped by police far exceeds their share of the enrolled students, which is more disproportionate when police initiate the stops compared to when the stops result from calls for service from the schools.

Police stop Black kids at rates far greater than their share of the student population. The disproportionality is worse when police initiate the stop, rather than when schools call the police to come handle a student issue.

School police, according to the report, also frequently failed to identify when the students they stopped had disabilities. This was made apparent by a wide gap between the data that school police reported to the federal government versus what school administrators reported. Moreover, school-based officers often simply reported “reasonable suspicion” as a reason for a stop, without elaborating.

“When police fail to comply with the reporting law, it not only masks over the degree to which students are profiled by race and disability status, it further breaks down trust and robs educators, policymakers and the community of the critical information they need to evaluate the impact of police presence on the student body,” said Dan Losen, Director of the Center for Civil Rights Remedies and lead author of the report.

The researchers suggest better data collection and analysis, especially of police stops. The state should also “encourage districts to engage in more frequent and timely reviews of discipline data and disparities so that the assessment of the current year’s practices can inform the development of the next year’s budget.” And there should be tangible consequences for backsliding school districts. Community members most heavily impacted by excessive school discipline should be involved in data review and in creating remedial plans, as well, according to the report.

“I hope this report encourages the state and districts to invest more in reforming school discipline practices, in ways that support teachers and expand the most effective alternatives,” said Losen. “Given widespread inaccuracies in the policing data, the data we have now should be carefully analyzed, so that the areas of greatest need are not being over-looked, hampering efforts to expend resources where they are needed most.”

Lead photo of LA School Police Department vehicle by Chris Yarzab, Flickr.

[…] Source link […]