Apr 2, 2024 12:59 PM

Saxophonist, Sonic Explorer Casey Benjamin Dies at 45

Casey Benjamin, the alto saxophonist, vocalist, keyboardist and producer who stamped his distinctive sounds on the…

More than a mere rarity, the new A Love Supreme: Live In Seattle is an avant-garde gem that offers new insights into Coltrane’s iconic work.

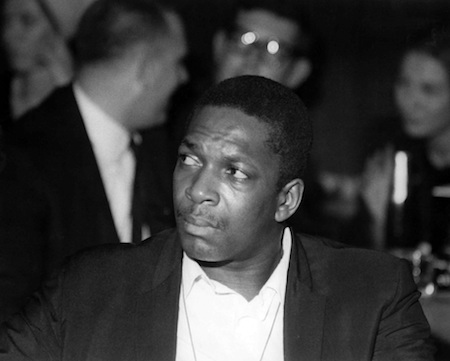

(Photo: Raymond Ross Archives, DTSImages)Until last year, John Coltrane was widely thought to have performed his masterpiece A Love Supreme only once live, on July 26, 1965, at the Festival Mondial du Jazz Antibes, in France.

That assumption was upended with the October 2021 release on Impulse! of a private recording made some two months later, on Saturday, Oct. 2, 1965, the last night of a six-night stand at Seattle’s Penthouse jazz club, the same engagement that also yielded the professionally recorded album Live In Seattle. The new tapes were found by Seattle saxophonist Steve Griggs in a vast collection left by another Seattle sax man, the late educator and activist Joe Brazil. Griggs made the discovery while sorting and digitizing Brazil’s collection of 750 reel-to-real tapes and 80 videos, many made while Brazil taught jazz history at the University of Washington. Griggs still remembers the exact date he realized what he had found.

“It was April 24, 2015,” he said. “I heard ‘Psalm’ first, and I was blown away, because I knew it was rare, that he never played it in public, except in France. But then when I turned the tape over and realized here’s Joe Brazil doing his matinee set, then it ends, then the next thing is the opening fanfare (of “Acknowledgment”), and — oh, my God! — I realized the whole suite is here.”

More than a mere rarity, the new recording — A Love Supreme: Live In Seattle (Impulse!), named Historical Jazz Album of the Year in the 70th Annual DownBeat Critics Poll — is an avant-garde gem that offers new insights into Coltrane’s iconic work. At 75:28, it runs more than twice as long as the original studio recording and has a loose, open-ended, wilder feel, which lives up to the Penthouse billing of a “John Coltrane Jam Session.” In addition to the members of what is now known as the classic quartet — pianist McCoy Tyner, bassist Jimmy Garrison, drummer Elvin Jones — the Penthouse band featured saxophonist Pharoah Sanders and bassist Donald Rafael Garrett, plus then-Seattle resident, alto saxophonist Carlos Ward, who sat in after opening for Coltrane as part of Brazil’s band on the Saturday matinee. The new players brought the shrieks, dissonance and diffuse rhythmic patterns of free-jazz to the bandstand, as well as doubling atmospherically on an array of percussion instruments.

Between the four movements of the original piece — “Acknowledgement,” “Resolution,” “Pursuance” and “Psalm” — Coltrane made room for solo features, presented rather arbitrarily on the album as separate tracks called “interludes.” The first is a sinuous bass duet, with Garrett playing deftly in the upper range; the second, a smacking solo by Jones with some splendid cymbal work. Interludes three and four are actually one long, often jaunty solo by Garrison that was interrupted by a change of reels (admirably spliced). Surprisingly, and perhaps a disappointment for some listeners, the sidemen’s solos outshine those of Coltrane himself. Tyner thunders and sparkles through a long, splendid outing on “Pursuance.” Sanders howls with intensity on “Acknowledgement” and “Pursuance”; and Ward offers a stuttering, urgently expressive solo on “Resolution” that makes it clear he has been listening to both Ornette Coleman and Eric Dolphy.

Many locals still vividly remember Coltrane’s engagement at the Penthouse, which regularly hosted A-list acts such as Miles Davis, Stan Getz, Carmen McRae and Oscar Peterson. Bassist David Friesen, who along with Ward played in the house band with Brazil, recalled that “everyone seemed to know that something special was going to happen.”

Indeed, the program was a shocking departure. The first couple of nights, the sets went on so long that Penthouse owner Charlie Puzzo, though no philistine and an adamant champion of jazz, told Griggs he had to ask Coltrane to take breaks so he could turn the house and sell more drinks. Coltrane complied, but the crowd was still not quite ready for what it heard.

“A lot of people, myself included, still had in mind Coltrane the ballad player with the Miles [Davis] Quintet,” said Seattle DJ Jim Wilke, who broadcast part of the Thursday night set on KING-FM. “It was hard to get a handle on.”

For Seattle bassist Pete Leinonen, Ward was the clear standout of the night. Coltrane apparently agreed. After the set, he encouraged Ward to move to New York, where he later famously played with Abdullah Ibrahim’s jazz octet, Ekaya.

Such on-the-scene comments highlight just how differently we regard A Love Supreme today than we might have in 1965, none moreso than this intriguing recollection by Seattle composer-pianist Marius Nordal:

“I saw the Saturday one where he filled the set with just one piece. It was so powerful that at the end, people were glassy-eyed and stunned and there was little applause. One professional-looking guy with a grey goatee stood up to do a lonely, clapping ovation … as if to say, ‘What’s wrong with you people? Don’t you realize what you’ve just heard?’”

That night in the fall of 1965, A Love Supreme had only been on sale for nine months. It’s a good bet that very few people knew what they were hearing, especially since Coltrane never even announced the piece.

It’s as if, said Coltrane biographer Lewis Porter, Coltrane were telling his band, “‘You want to jam on it? That’s fine.’ Trane was almost ridiculously humble. He was not self-important, so even if he may have thought of this [A Love Supreme] as his big statement, that doesn’t mean he saw it as an important moment for everyone else.

“I am a very level-headed person,” he added. “I never jump out of my seat. But believe me, when I heard this my heart was pumping.”

Could other live versions of A Love Supreme surface? “Hearing him play it informally in October ’65 makes me think there’s no reason to assume that he didn’t play it at other clubs,” Porter said.

Still, why did Coltrane perform A Love Supreme in Seattle? Joe Brazil may be the answer. Brazil knew Coltrane in Detroit, where they often compared notes on Eastern spirituality, in particular, the Hindu scripture the Bhagavad Gita. In a 1989 oral history interview, Brazil said he had “about 10 versions of the Gita, the ‘Hindu Bible,’ and Trane was interested in some of those versions that I had.” While Coltrane was in Seattle, he and Brazil spent time discussing spiritual interests and also recorded the overtly spiritual album Om, with Brazil playing wooden flute. It’s not a stretch to credit Brazil with putting Coltrane in the frame that prompted him to revisit A Love Supreme. Griggs agrees.

“The more I tried to re-create the scene of Coltrane in Seattle, the more Joe Brazil became the main thread,” he said.

Whatever the reason behind Coltrane’s decision to revisit his masterpiece, we are lucky to have it and can only hope it will lead to the discovery of many more. DB

Benjamin possessed a fluid, round sound on the alto saxophone, and he was often most recognizable by the layers of electronic effects that he put onto the instrument.

Apr 2, 2024 12:59 PM

Casey Benjamin, the alto saxophonist, vocalist, keyboardist and producer who stamped his distinctive sounds on the…

“He’s constructing intelligent musical sentences that connect seamlessly, which is the most important part of linear playing,” Charles McPherson said of alto saxophonist Sonny Red.

Feb 27, 2024 1:40 PM

“I might not have felt this way 30 to 40 years ago, but I’ve reached a point where I can hear value in what people…

Albert “Tootie” Heath (1935–2024) followed in the tradition of drummer Kenny Clarke, his idol.

Apr 5, 2024 10:28 AM

Albert “Tootie” Heath, a drummer of impeccable taste and time who was the youngest of three jazz-legend brothers…

“Both of us are quite grounded in the craft, the tradition and the harmonic sense,” Rosenwinkel said of his experience playing with Allen. “Yet I felt we shared something mystical as well.”

Mar 12, 2024 11:42 AM

“There are a few musicians you hear where, as somebody once said, the molecules in the room change. Geri was one of…

Henry Threadgill performs with Zooid at Big Ears in Knoxville, Tennessee.

Apr 9, 2024 11:30 AM

Big Ears, the annual four-day music celebration that first took place in 2009 in Knoxville, Tennessee, could well be…