Please note, this article was originally written, produced, and posted on December 2nd, 2021 after it was announced he was being inducted.

You can sum up a large part of Gil Hodges’ Hall of Fame case with an argument that didn’t happen.

It was the bottom of the sixth inning of game five of the 1969 World Series. Hodges’ Mets, improbably leading the series 3-1, were losing the game 3-0; Jerry Koosman had allowed home runs to Frank Robinson and starting pitcher Dave McNally in the third inning. Cleon Jones led off the bottom of the sixth for the Mets. McNally’s first pitch was a curve, down and in. It hit the dirt near Jones’ foot and bounded sideways, towards the Mets’ first-base dugout. To all the world, it seemed that it had hit Jones in the foot. All the world except home plate umpire Lou DiMuro, that is. DiMuro threw McNally another ball and called Jones back to the batter’s box.

Hodges came out to contest the call. Gil Hodges Jr., watching the game at Shea Stadium, remembers it well.

“The presentation,” he said. “Walking to home plate calmly and slowly, and looking at the ball. Back then, all the spikes would be cleaned and polished for the following day. So all the spikes had shoe polish on them. When he walked out there looking at the ball, gave it to the umpire, and showed him the spot on the ball, there was no reason for the umpire to doubt him.”

Hodges was calm, cool, and collected. DiMuro looked at the ball and saw a small black polish mark. He sent Jones to first base. Orioles manager Earl Weaver, who was ejected 96 times in his career including the previous day in game four, was angry — but DiMuro’s mind was made up. Hodges, the quiet man, had won the argument without ever arguing.

“The Quiet Man,” the title of a 1991 biography of Hodges by Marino Amoruso, summed Hodges up perfectly, his son told me. Hodges wasn’t loud, brash, or rude; he communicated calmly and clearly, and never lost his cool.

“Otherwise, he would have run to home plate, screaming and yelling with the shoe polish, instead of walking casually to home plate and showing it to the umpire,” Hodges Jr. said. “The complete opposite of the spectrum from Earl coming out of the other dugout.”

Jones took his lead off first. A few pitches later, Donn Clendenon hit McNally’s 2-2 pitch over the left field fence to bring the Mets within a run. Three innings later, the Mets won the 1969 World Series.

Would things have worked the same way if anyone else had been managing the Mets? It’s hard to say, but — probably not? Consider, for a second, the absolute absurdity of what this moment tells us about Gil Hodges. Hodges came out of his dugout holding a baseball with a black mark on it. It might have come from Jones’ foot; subsequent reporting revealed that it might have come from Jerry Koosman’s foot, as Hodges, just to be safe, instructed Koosman to kick it before he left the dugout, although the entire park was certain that the pitch really had hit Jones; for all DiMuro knew, it might have been a different baseball altogether. Hodges walked up to DiMuro and showed him a black mark on a baseball that could have been anything — and DiMuro, in effect, said, “Sure, Gil. I trust you.”

Isn’t that absurd? Isn’t it completely ridiculous? Can you imagine any manager in baseball today, anyone at all, succeeding at something like that? Of course not. It could never happen, and might well never happen again, because we may never see another baseball figure like Gil Hodges.

What kind of man was Gil Hodges? He was an uncommonly hard worker, a pleasure to play with and to umpire, calm and respectful to what teammates sometimes thought was a fault. He was a leader of men, a peacekeeper on the field, a beloved father, son, teammate, and manager, and a U.S. Marine and Bronze Star recipient. His death in 1972 at age 47 robbed baseball of decades of his presence in the game.

It’s all that, plus the fact that he was the premier first baseman of the 1950s and hit 370 home runs and was an all-time great defender at his position, plus the fact that he managed the 1969 Mets to one of the greatest upset wins of all time and more than 50 years later, they still talk about him reverentially, that makes Gil Hodges a Hall of Famer. Taken individually, maybe each piece doesn’t quite get there. But consider the totality of Hodges’ career and the depth of his devotion and contribution to baseball, and it’s almost inconceivable that the Hall still hasn’t admitted him.

“He was such a noble character in so many respects,” wrote Arthur Daley of the New York Times in 1972, soon after Hodges’ funeral, “that I believe Gil to have been one of the finest men I met in sports or out if it.”

Hodges has earned more Hall of Fame votes than anyone else in history not to eventually be admitted. Soon, he’ll have another chance. On Sunday, the Golden Days Era Committee will consider Hodges along with nine other candidates. By one count, it will be the 35th time Hodges is considered for induction. This time, the Hall must set things right. The Hall must end its long miscarriage of justice, and finally enjoy the privilege of having Gil Hodges among its ranks.

***

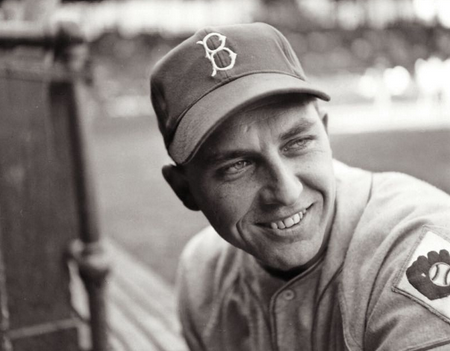

Initially, Hodges was a shortstop. Many people don’t know that, including me until these last few weeks. Most people also don’t know that on March 20th, 1943, Hodges, then a student at St. Joseph’s College in Indiana, was leading a Red Cross fundraising drive. That’s not strictly related to his baseball journey, but I couldn’t resist.

“Allison Crippled In City Series,” blared a headline in the Indianapolis Star on August 26th, 1943. The story continued:

Allison’s hopes of winning the Indianapolis Amateur Baseball Association’s city series were dealt a severe blow yesterday when Gil Hodges, regular shortstop, headed for Brooklyn to sign a contract with one of the Dodgers’ “farm” clubs.

There were already murmurs in the Dodger front office that Hodges would eventually have to shift positions. Indeed, Hodges made one appearance for the 1943 Dodgers as a third baseman in the last game of the season, going 0 for 2 with a walk. 11 days later, he enlisted in the Marine Corps. He served for two and a half years, and participated in the battle of Okinawa, for which he was awarded the Bronze Star.

After his honorable discharge early in 1946, Hodges returned to the Dodgers, who sent him to their Newport News farm team in the Piedmont League. This time, though, something was different: they’d decided to convert him to a catcher. Hodges took the change in stride. He batted .278/.378/.436 for the season, and was named to the league’s All-Star team as a catcher. In 1947, he joined the big-league club. Then came 1948, when Roy Campanella came along. At the end of June, Hodges moved to first base. He would hold down the job for more than a decade.

His breakout began in 1949, when at age 25 Hodges batted .285/.360/.453 with 23 home runs. 1950, though, was when Hodges came into his own. He batted .283/.367/.508 with 32 home runs. For the rest of the decade, he didn’t slow down.

“I grew up in St. Louis, and watched him as a kid with those great Dodger teams,” Art Shamsky told me. “I saw what a great player he was, offensively and defensively.”

In the 1950s, Hodges batted .281/.369/.514, averaging 31 home runs a year. He won World Series titles in 1955 and 1959 and was a key part of both, driving in both Dodger runs in game seven of the ’55 series and batting .391 in the ’59 series. After a brief stint as the Mets’ first first baseman, Hodges was traded to the Washington Senators, whereupon he immediately retired as a player to become the Senators’ manager.

Some of Hodges’ Dodgers teammates couldn’t see him as a manager. “I was surprised that Hodges became a manager,” Carl Erskine remembers telling Tom Seaver. “We thought he was too passive a personality, he wouldn’t be tough.”

“Don’t worry about Hodges being tough,” Seaver responded. “All he has to do is give you that look. And if he gives you that look, it’ll singe your shorts off.”

“He didn’t have to say a lot,” Erskine told me. “He was a strong leader, and everybody knew it. He didn’t have to shout or throw the chairs or anything. He was totally respected. He was a strong person, but he wasn’t a loud person.”

Hodges managed the Senators for five years, and while his rosters were never strong, the team improved from 62-100 in 1964 to 76-85 by 1967. Then Hodges returned to New York. In 1967, the Mets had gone 61-101. In ’68, they improved to 73-89-1. In 1969, they won 100 games.

“The first thing he did with the Mets was teach them that it’s not okay to lose,” Gil Hodges Jr. told me. “Someone’s going to win and lose every day, but it’s not okay to lose. And when you put on that uniform, you should feel privileged, because you become special. There’s thousands of people who’d like to put that uniform on. So when you put it on, you need to give 100% at everything that you do, in every aspect of your job. That’s what he taught them.”

Shamsky remembers the first day of Spring Training 1968 — Shamsky’s first day as a Met, and Hodges’ first day as Mets manager. Hodges addressed the team, and no one had any doubt about what he expected of them.

“He said, ‘listen. From now on, you guys are not going to be the same old Mets,’” Shamsky said. “And you could see that he was serious.”

“He was a real tough guy,” said Rod Gaspar, who debuted for Hodges’ ’69 Mets. He didn’t have to say too much to get our attention. We didn’t have too many issues with that ballclub. Gil was in control, and our teammates respected him big-time and what he wanted us to do.”

What Hodges wanted them to do was work together to win. That’s exactly what happened.

“That Met team was 25 guys pulling in the same direction,” said Rene LeRoux, Executive Director of the New York State Baseball Hall of Fame, which inducted Hodges last year. “Gil was the reason why they won.”

Believing in the importance of righty/lefty matchups, Hodges instituted platoon systems at several positions, and never wavered. Shamsky, for instance, a lefty, batted .538 in the 1969 NLCS, but then didn’t start game one of the World Series, because Orioles’ starter Mike Cuellar was also lefthanded.

“Everybody on that team believed in him,” Shamsky said. Some players, he said, felt the platoon system negatively impacted their career prospects — “and I was one of them. But we believed in it. We believed in him.”

That, Shamsky said, was what made Hodges stand out as a manager. It wasn’t just that the players believed in his strategies, although that was important too; it was also that in the ninth inning, with lefthanded Cuellar still on the mound for Baltimore, Hodges sent Shamsky up to pinch-hit, thus expressing that while Shamsky hadn’t gotten the start, he still had his manager’s confidence.

“That’s his greatest quality,” Shamsky said. “Being able to handle the players and get them to believe in what was best for the team.”

After the ’69 season, Hodges kept right on managing. The Mets had played far beyond their capabilities to win the division and the World Series; their pitching was excellent, but the Mets of the early 1970s could never seem to muster much on offense. The ’71 team only had one everyday player with an OPS above .800. Hodges led the Mets to back-to-back 83-79 finishes. He died shortly before the 1972 season began.

The wrap on Hodges’ career is actually pretty simple. He hit 370 home runs, batted .273/.359/.487, and was the preeminent offensive and defensive first baseman of the 1950s. He was an eight-time All Star, won three Gold Gloves, and probably would have won ten to twelve if the award had existed before 1957. Then he retired, took over a Mets team that had never won more than 66 games, and managed them to the greatest upset win of all time.

***

That’s Hodges as a player and a manager. On their own, those two qualifications — premier first baseman of a decade, plus managing an upstart team to one of the greatest victories ever — seem like they should be more than enough to merit Hall of Fame induction. But then his character enters the equation, and his case gets even stronger.

“He’s a Hall of Fame human being. He’s a Hall of Fame person,” LeRoux said. ““He never had a steroid problem, he never drove a car into a telephone pole, he didn’t slap anyone. This guy was one of the nicest gentlemen the game of baseball has ever seen.”

Gil Hodges, the old folk legend goes, was the only player never booed in Brooklyn. Except it’s not a folk legend. Carl Erskine says it’s true.

“I’m here to testify, I never heard them boo Hodges in Brooklyn,” he told me. “It didn’t seem appropriate that these raucous fans in Brooklyn would have such a sentimental and soft touch on Hodges, but they embraced his behavior. First base is a busy place. There’s a lot of close plays. And the way Gil handled it, it reflected somehow that the fans respected him for how he played his position.”

Erskine remembers all the opportunities Hodges had to get angry — and how he almost always refused.

“You can imagine how many close plays happen at first base, and how many opportunities there would be to confront the umpire about a close call,” he said. “That will give you some idea of the restraint he had. The umpire made the call, and that’s the way it was, that was it.”

Everyone knew about Hodges’ reputation. Dodgers’ manager Charlie Dressen once offered Hodges $100 if he would argue enough to get himself thrown out of a game. The bill never came due.

Hodges himself knew about how people saw him, and wasn’t above making fun of himself for it. Once, Erskine remembers, umpire Dusty Boggess called Hodges out on a pitch below his knees. Hodges quietly returned to the bench. His teammates were furious.

“He’s taking the bread and butter right out of your kid’s mouth!” Hodges’ Dodger teammates were yelling at him. “You don’t ever say a bad word to these umpires when they call these terrible pitches and take the bat out of your hand! You’ve gotta quit that!”

“Oh, okay, okay,” Hodges responded. “The next time I go to the plate and Dusty Boggess is back there, I won’t even ask him how his wife and kids are.”

Hodges wasn’t just respectful to umpires. He was fiercely loyal to his teammates — and even opponents realized that he wasn’t someone to fight with.

“There were a number of instances on the field, around second base with Jackie, that Gil stepped in,” Erskine said. “Everybody seemed to respect Gil. He was pulling guys off the pile, and nobody was taking a fist to Hodges.”

“If he raised his voice a little bit,” Shamsky echoed, “you could see that he was somebody you didn’t want to mess with.”

That’s an aspect of the story that’s rarely discussed, but feels more important than the coverage it’s been given: for years, Hodges played first base, and Jackie Robinson played right next to him at second.

“They often talked about Pee Wee playing alongside of Jackie,” Erskine said. “Well, Hodges played alongside Jackie on the other side, and he had just as much to do with keeping the peace. Maybe more than anybody.”

In an MLB.com essay, Vin Scully, who watched Hodges for more than a decade with the Dodgers, wrote about the dynamic between Hodges and Robinson. Once, he remembered, the two players were chasing a foul pop-up near the first base stands at Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis when a whiskey bottle came flying from the upper deck, clearly thrown by someone aiming at Robinson. Thankfully, it missed.

“I remember Gil patting Jackie on the back,” Scully wrote, “as if to say, ‘Hey, you’re not alone. I’m with you.’”

Robinson noticed Hodges’ presence. Years later, at Hodges’ funeral, Gil Hodges Jr. was sitting in a church pew when Howard Cosell tapped him on the shoulder. Cosell was a friend of the Hodges family. Hodges Jr. followed Cosell out of the church and around a corner, where he found a car double-parked.

“Hop in the back of the car,” Cosell told him. Hodges Jr. got in. Jackie Robinson was sitting in the car, crying hysterically. Robinson hugged Hodges Jr.

“Next to my son’s death, this is the worst day of my life,” Robinson told him.

As a manager, Hodges was every bit as kind and respectful as he’d been as a player. Dave Kaminer went to his first Dodgers game in 1950, and Hodges instantly became his favorite player. 18 years later, though, Kaminer was a young sports reporter for a Westchester paper, covering the Mets. The week before the 1968 season began, though, he was drafted. He sent Hodges a note explaining what had happened. “Looks like I’m not going to be around,” he wrote.

Kaminer reported for induction on April 14, 1968. But he got lucky: examiners found psoriasis on his ankle and sent him home. A few days later, he was at Shea Stadium, covering Hodges’ first home game as Mets manager.

When Hodges saw him from across the field, he pointed at him. “Stay where you are,” Hodges called. He made his way over to Kaminer and asked what had happened. Kaminer explained. Hodges, the former Marine, smiled.

“That’s great,” he said. He grabbed Kaminer’s hand and shook it. At the time, maybe it was painful; Hodges was famous for his strong, enormous hands.

“He would shake hands with you, and you’re hoping you would still have a hand after that,” Kaminer said. But all the same, the personal touch from the Mets manager and personal hero wasn’t exactly what he’d expected.

“Made me feel like a million dollars,” Kaminer said. “The part of the Hall of Fame that says ‘character,’ that should have Gil’s picture.”

Rod Gaspar remembers an argument he once had with a clubhouse attendant. The attendant told Hodges about it. Soon, Hodges called Gaspar into his office.

“That’s the last time I was ever in his office,” Gaspar said, chuckling. “No problems after that. If he saw any little thing that could disrupt the club’s momentum, he would take care of it real quick.”

They say, “never meet your heroes.” Gil Hodges, it turns out, was the exception.

“When you’re a kid, we all have heroes,” Kaminer said. “And very few of us get to meet our heroes. And some of us, when we finally meet them, we find out, ‘jeez, this guy’s a jerk.’ But Gil was the best. It made me feel wonderful about my choice.”

***

There aren’t many critics of Hodges’ Hall of Fame candidacy. As Gaspar said, “I’ve never heard anybody say that he doesn’t belong in the Hall of Fame.” But there are a few.

The basic arguments against Hodges go like this. First, his career numbers don’t measure up to other Hall of Fame first basemen. Second, he may have managed the ’69 Mets, but overall, he was under .500 as a manager. Third, he may have been a wonderful person, but being a nice guy doesn’t make you a Hall of Famer.

I don’t buy any of them, for a number of reasons. First off, right at the beginning of his career, Hodges lost two seasons to World War II. Given those two seasons back, Hodges likely develops as a hitter far faster; he makes the big-league club in 1945 or 1946 with his development curve two years ahead of where it ended up; he almost certainly finishes his career with more than 400 major league home runs, a nice round number that, combined with everything else, seems like enough to win over even some of Hodges’ critics.

Hodges also suffered from the simple fact that the Gold Glove didn’t exist until his age 33 season. If he’d retired with 400 home runs, eight All-Star appearances, and nine or ten Gold Gloves (which, as the widely acknowledged best defensive first baseman of the 1950s and winner of the first three N.L. Gold Gloves at first base from 1957 to 1959, he seems fairly likely to have won), his Hall of Fame case would have been a no-brainer. He probably would have gotten in during his first few years on the ordinary ballot.

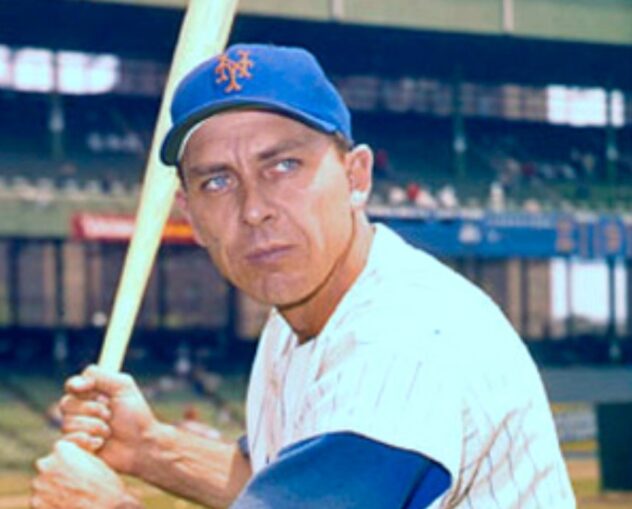

Photo: Gil Hodges, MLB.com

Second, sure, Hodges was under .500 as a manager. There’s one obvious problem: would he have remained under .500 as a manager if he hadn’t died at age 47, but rather, had gone on to live a long baseball life, managing for decades? Maybe, maybe not. Even just working with his existing managerial portfolio, though, I’m not too impressed by arguments about his win-loss record. Hodges took over a terrible Senators team, slowly but surely started turning the team around as he learned how to manage, then left for New York and managed the Mets into the history books. He is universally regarded as one of the three best managers in Mets history, along with Davey Johnson and Bobby Valentine, and those who played for him vouch endlessly for what an excellent manager he was, and how deserving he is of Hall of Fame induction. Of the Golden Days Era Committee ballot, Ron Swoboda told me, “If that process can’t include him in the Hall of Fame, the process is wrong.”

Also, managerial record sometimes just doesn’t capture the full picture of a manager’s contributions to baseball. Connie Mack was below .500 as a manager. So was Felipe Alou (he’s not in the Hall of Fame, but he certainly should be). So was Frank Robinson. So was Ron Gardenhire. So was Gene Mauch. Some of these guys aren’t in the Hall of Fame, of course, but of the ones who aren’t, none were also the best first baseman of a decade — and none managed the 1969 Mets. Sometimes a manager’s contributions to baseball aren’t reflected in their overall record. That’s especially likely when a manager dies at age 47 instead of getting to spend decades perfecting his craft.

The “managerial winning percentage” argument seems to just be a sly way of saying something else that Hodges critics don’t want to say out loud: Hodges wasn’t actually a good enough manager for it to push him over the line for Hall of Fame induction. But A) there’s the matter of his tragic, untimely death, and B) his players vehemently disagree.

“One of the best managers ever, in my book,” Gaspar told me. “He deserves it, but not just now. 50 years ago, he deserved it. Always has deserved it.”

“He was a manager who managed by feel,” Shamsky said. “He knew all the players on his team, he knew the strategies of the game. He was a step ahead of everyone else.”

Third — yes, of course being a great guy isn’t enough to make someone a Hall of Famer on its own. I think I’m a great guy; I don’t belong in the Baseball Hall of Fame, and you may quote me on that. But when you put it together with being the premier first baseman of a decade and managing one of the greatest upstart winners of all time, doesn’t it start to matter more?

Character counts. Character should count. The argument against counting character is a sort of rhetorical trick; it groups players into a binary, where the only possibilities are that someone is either a great guy or they’re not. Obviously, there are a lot of nice people in the world, so the “great guy” group is pretty big, which Hodges’ opponents can use to render character meaningless: “There are lots of nice guys! Are we going to start inducting every nice guy who hits a few home runs into the Hall of Fame?”

The key point that this argument gets wrong is that Hodges was not just another nice guy. This, more than anything, is the defining feature of his candidacy. If you look at Hodges and see a nice guy but nothing more, than maybe it makes sense to dismiss his Hall of Fame qualifications. But when you hear the stories about Hodges, you realize that he wasn’t just a “nice guy.” He was an unfailingly and uncommonly kind, respectful, respected, thoughtful, hard-working, conscientious leader, who poured his heart and soul into the game of baseball and in the end, gave it his life.

It’s not hard to see how much more than a “nice guy” Hodges was, and what a rare character he brought to baseball.

“Gil often came over in the middle of a tough ballgame, men on base, after a play at first base and time was out,” Erskine said. “He’d walk over to the mound and bring the ball to me. And in doing that, he’d say, ‘if anybody can get out of this jam, you can do it.’”

When he rounded the bases on a home run, Kaminer told me, he would pause to blow a kiss to his wife.

“Gil blew a kiss to his wife,” he said. “Maybe it’s time for baseball to blow a kiss to Gil.”

At Hodges’ funeral, similar sentiments were in the air.

“I’m sick,” said Johnny Podges. “I’ve never known a finer man.”

“If you have a son,” said Pee Wee Reese, “it would be a great thing to have him grow up to be just like Gil Hodges.”

“Gil Hodges is a Hall of Fame man,” said Roy Campanella.

“The older I get, the more I think Gil Hodges should be in the Hall,” said George Vecsey, longtime New York Times reporter who covered Hodges as both a player and manager. I reached Vecsey via email. “He was a fine man and a great player.”

“He was a class player,” Erskine said. “You wouldn’t be wrong to point to Hodges to your kids and say, ‘that’s the kind of gentleman you ought to grow up to be like.’”

“I am often asked who the best ballplayer was that I watched during my broadcasting career,” Scully wrote in his essay. “In looking back over my 67 years behind the microphone, I was truly blessed to watch firsthand so many of the all-time greats performing at their very best on the biggest stages in the game’s history. It is truly impossible for me to single out just one player. However, in terms of the players I watched who performed at a high level on the playing field, but at an even higher level off the field in how they lived and carried out their lives, my response is an easy one — Gil Hodges.”

Simply put, most people don’t get talked about this way. You have to be more than just a nice man for people to tell their sons to grow up to be like you. Vin Scully broadcast Dodger baseball for 67 seasons, and Gil Hodges, he says, had the best combination of on-field play and off-field character that he ever saw. You don’t hear that every day.

Character counts. Character has to count. And Gil Hodges is the picture of strong baseball character more than almost anyone else. He was the shortstop turned third baseman turned minor league All-Star catcher turned elite big league first baseman, who never complained but always did what his team needed. He was the manager who taught a young Mets team that it wasn’t okay to accept losing, and that wearing a Major League Baseball uniform was a privilege that came with responsibility — and that if they embraced that responsibility, selfless teamwork, and determination, they could shock the world.

“He was a player whose major-league career was interrupted by World War II,” Swoboda told me. “He was a manager whose career was interrupted by death. If you can’t simply add up what he was as a player and as a citizen, and include in it the character that he carried with him every day, and add to that what he was as a manager…if you can’t come up with a Hall of Famer, you really shouldn’t be in a position to vote, in my humble opinion.”

Inducting Hodges will also mean inducting the last rock of the Golden Age Brooklyn Dodgers. Campy, Jackie, Pee Wee, and The Duke are all there, but the team isn’t whole. They’re still waiting for Gil.

“When you see a teammate make it to that status, part of you went with him,” Erskine said. “That’s what I’ll feel if Gil makes it. I’ll feel a piece of that. If he goes into the Hall of Fame like Pee Wee and Duke Snider and Campanella did…I’ll feel like a piece of me went with him.”

Hodges belongs in the Hall of Fame because of his accomplishments as a player, a manager, and a human being. He belongs because he was the best first baseman of the 1950s on both sides of the ball. He belongs because he was the kindest, most respectful, most devoted person that many people ever played with or played for. He belongs because he taught the Mets to win. He belongs because of everything that he did.

When he was young, Hodges Jr would travel all over the country with his father’s team. He remembers sitting in the visiting manager’s office at Memorial Stadium in Baltimore on October 11th, 1969, reading over the stat sheets for both teams before game one of the World Series.

“I couldn’t even comprehend that they were going to play this team,” he told me. “They were a juggernaut.”

The Orioles looked unbeatable. They had gone 109-53 in the regular season. They had two 20-game winners in their rotation, along with a young Jim Palmer, who had just put up a 2.34 E.R.A. They had Boog Powell (37 home runs, .942 OPS) at first base, solid-hitting Davey Johnson at second, elite defender and competent hitter Mark Belanger at short, and Brooks Robinson, the greatest defensive third baseman of all time, at third. They had Frank Robinson and his .955 OPS and 32 home runs in right field, and two OPS’s above .800 in center and left. The next year, Palmer would join the 20-game winners, and the Orioles would win 108 games and beat the Reds four games to one in the World Series.

Looking at the stats sheets, Hodges Jr. was confounded. “Dad,” he said, “what are you doing on the field with this team?”

Hodges stood up. He walked to his office door and closed it. He sat back down.

“Don’t say that again,” he said. “There’s 25 guys outside who believe that they can win.”