A SOBER APPRAISAL

Reducing New Mexico’s extraordinary alcohol death rate will require a whole-of-society approach.

At a 12-steps meeting in Albuquerque’s foothills, one of hundreds held each week statewide, there were cowboys, Anglo women in golf shirts, and Hispanic day laborers. A woman without housing asked around for a place to stay the night. A downcast man in nurse’s scrubs said he had relapsed but hoped to go home that night, if his wife would have him.

New Mexicans can’t neglect the state’s enormous alcohol problem even if they want to. Tens of thousands have to confront it each day in their roles as clinicians and cops and probation officers and teachers, as family of people dependent on alcohol, and in personal struggles with addiction.

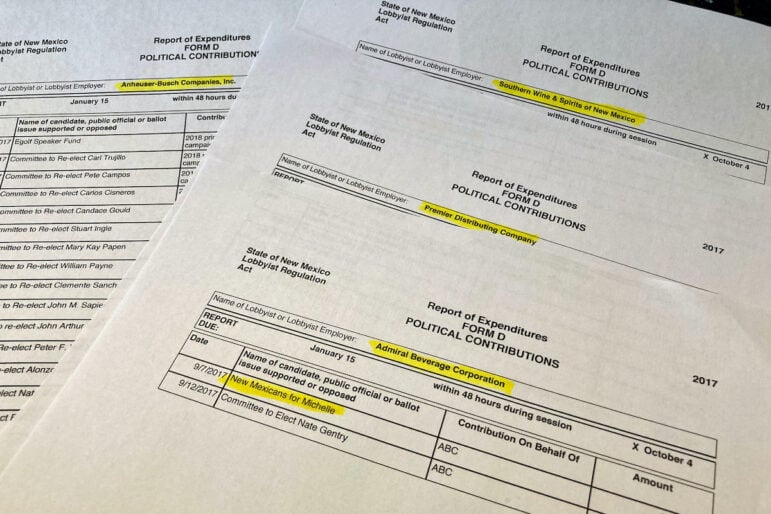

Yet for years, the state’s political leaders have largely turned a blind eye, failing to take substantive, statewide action to curb the escalating crisis. Instead of reducing hazards for people who consume alcohol, they have improved the business climate for people who sell it. Last year, as the number of alcohol-induced deaths in the state hit record highs, legislators and Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham made it easier to get alcohol in restaurants and via home-delivery.

On more than half the measures recommended for reducing alcohol-related harms by the Community Preventive Services Task Force, an independent panel of scientific experts, the New Mexico Department of Health acknowledges the state “needs improvement” or is moving in the wrong direction.

Many people — including those who benefit from alcohol sales — view the challenge with fatalism.

“We do have an alcohol problem in New Mexico. We always have and always will,” said lobbyist Ruben Baca, who in 2017 helped kill one of the recommended measures, an increase in alcohol taxes.

In 1990, many thought the state’s elevated rate of intoxicated driving crashes couldn’t be changed — until lawmakers mustered a whole-of-government response and cut the rate of fatal crashes by two-thirds.

And overwhelmed by a wave of opioid overdose deaths long before it hit the nation as a whole, New Mexico developed policies that experts credit with preventing deaths from climbing higher.

Not typically thought of as an innovator, in both cases New Mexico adopted first-of-their-kind laws that later spread across the country. The state required motorists convicted of intoxicated driving to install ignition interlocks, and made it easier for people who inject drugs to report overdoses to emergency responders and access the medication naloxone to revive overdose victims.

Today, no state has a higher rate of alcohol-related deaths than New Mexico, including those that consume more alcohol and where more residents drink. “Drinking is more dangerous in New Mexico,” said Michael Landen, the state epidemiologist from 2012-20, so the state needs stronger safeguards than other places, too.

And the rest of the country is again following in our footsteps: alcohol-related deaths rose 25% nationwide in 2020, according to the most recent data. If New Mexico rises to the challenge of addressing its drinking problem, it could create a roadmap for other states.

Actions we can take

To significantly reduce alcohol’s harms would require efforts across New Mexican society, including by the governor, the Legislature, courts, clinicians, not to mention alcohol producers, sellers, and drinkers. In interviews, state and national experts suggested necessary elements:

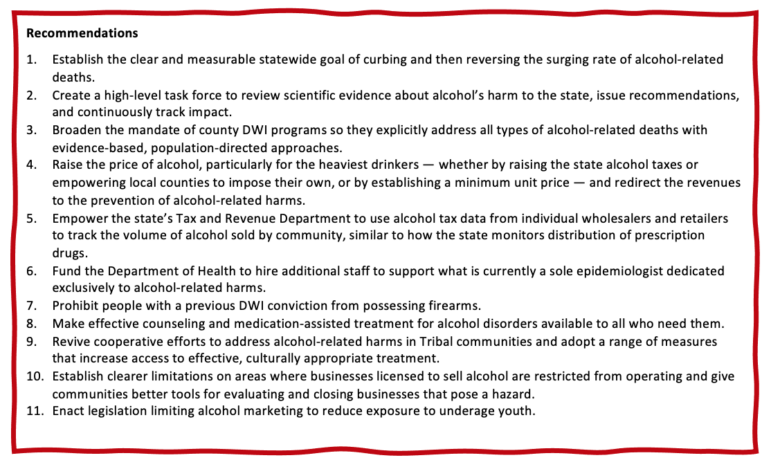

1. Set a measurable and meaningful goal, and lead

First, the state needs to acknowledge the problem and commit to addressing it, said Landen. Lawmakers could enshrine the clear, measurable goal of reducing alcohol-related deaths and empower a high-level task force to propel action — “to keep the recommendations coming and the evaluation moving forward.” A potential template is the state’s Overdose Prevention and Pain Management Advisory Council created in 2012. Lawmakers could require the task force to make annual reports to the Legislature so it doesn’t “disappear into irrelevance,” said David Jernigan, a professor at the Boston University School of Public Health.

2. Renew the fight against DWI, and look beyond it

Thirty years ago, New Mexico’s campaign to reduce intoxicated driving significantly changed behaviors and saved lives — but in the last 15 years those reductions bottomed out. There are ways to renew those efforts.

The state’s .08 legal blood alcohol concentration is lax — a 180-pound person might consume four drinks in an hour without exceeding it — and lawmakers could lower it to .05. This is already the standard in many middle- and high-income countries. In Utah, the first state to implement it, fatal crashes fell afterward by 20%, faster than in neighboring states or nationwide.

New Mexico could expand DWI Recovery Courts to all counties. These courts are an alternative to incarcerating people with repeat DWI convictions, and typically supervise participants through 12 to 18 months of substance use treatment. Participants aren’t allowed to drink and are monitored with random drug tests at least twice a week to ensure they don’t. Those who don’t put in the required effort may be returned to jail to serve out their sentences. “It’s not a cakewalk,” said Judge Christine Rodriguez, who runs Bernalillo County’s DWI Recovery Court, the state’s largest. Participants’ rate of rearrest is low, yet most counties lack such programs, including those where repeat convictions account for as many as half of DWIs. (After years without DWI Recovery Courts, Rio Arriba and McKinley counties are starting them this year, according to the Administrative Office of the Courts.)

But deaths caused by intoxicated driving represent only one in 10 of the state’s alcohol-related fatalities and should be addressed as a facet of a much larger problem. The state has long funded Local DWI (LDWI) councils in each county to address intoxicated driving but they focus on problem drinkers rather than population-wide strategies to reduce alcohol consumption. Landen said the Legislature could broaden their mandate to explicitly address all alcohol-related deaths with evidence-based approaches.

3. Raise the price of alcohol

Experts agreed the most important step New Mexico can take to reduce alcohol-related deaths is to make it less affordable to drink excessively by raising alcohol taxes.

“There are more studies of this than any other preventive intervention that we’ve done, and the findings are more consistent,” said Alex Wagenaar, a professor emeritus at the University of Florida College of Medicine. “As the tax goes up, alcohol problems go down.”

In New Mexico, Landen said an increase in alcohol taxes ought to be the “centerpiece” of any robust response to alcohol-related deaths, whether raised statewide or by empowering local counties to impose their own taxes, which McKinley County already does.

Raising the price of alcohol matters more than how the revenues from the tax hike are spent, experts say, but legislators typically focus on the latter. Rep. Jason Harper, R-Rio Rancho, a member of the House tax committee, said he didn’t object to a tax increase but insisted that its revenues go to alcohol treatment and prevention instead of the state general fund, where about half of alcohol tax revenues are currently deposited. A bill introduced last year would have made that change, diverting those funds to counties and a state-administered fund for Medicaid (where the state would reap matching funds from the federal government). The bill’s sponsor, Rep. Dayan Hochman-Vigil, D-Albuquerque, said she plans on reintroducing the bill in 2023.

There are other ways of reducing the affordability of alcohol, such as setting a price floor sellers cannot go below. In Oregon, 750ml bottles of 40-proof spirits must be priced at $8.95 or more. Ireland recently enacted a minimum unit price for alcohol, prohibiting sales for less than US$1.13 per standard drink, regardless of whether the beverage is beer, wine, or liquor. In contrast, the cheapest liquor sold at a Rio Rancho Wal-Mart is priced at 30 cents per standard drink.

4. Measure alcohol sales

To curb rising opioid overdose deaths, New Mexico began monitoring the distribution of prescription drugs to help crack down on dangerous prescribing practices. Landen said the Legislature could create a comparable monitoring system for alcohol, by authorizing the Tax and Revenue Department to use alcohol tax data from individual wholesalers and retailers to “track where alcohol has been purchased, in what settings, by what communities.”

The Legislature could also appropriate money to expand the state health department’s team that tracks alcohol-related harms. To address one of the largest preventable causes of death in New Mexico, the state currently employs just one alcohol epidemiologist.

Address the connection between alcohol and violence: Over 40% of New Mexican homicide victims were drinking at the time of their deaths, and alcohol is the most common intoxicant in violence in the state. Charlie Branas, the chair of the epidemiology department at Columbia University, said “there are many untapped opportunities” for the state to prevent violence by tackling alcohol.

Research has recently demonstrated that handgun owners with a prior conviction for intoxicated driving are four to five times more likely to commit violent or firearm crimes. Lawmakers could prohibit them from possessing guns. Scientists have also repeatedly shown that businesses that sell alcohol influence crime rates in their proximity. New Mexican policymakers and law enforcement could study whether the number and concentration of alcohol outlets have contributed to the state’s alarming rates of violence.

5. Address disparate harm to Native communities

Alcohol-related deaths in New Mexico are characterized by stark racial disparities. State and sovereign tribal governments share responsibility to close these gaps.

The most critical step is to establish a coordinated strategy, said Michelle Brandser, a member of the Navajo Nation and the Health Services Administrator for their Division of Behavior and Mental Health Services. The state and tribes have consulted but she urged “a renewed effort.” Better collaboration between the Indian Health Service and Navajo Nation to crosstrain the Nation’s limited behavioral and mental health workforce is needed too, she said.

Many experts suggested ways to make effective treatment more accessible to Native people. Spero Manson, who is Pembina Chippewa and a professor of public health and psychiatry at the University of Colorado, recommended that Medicaid, the government’s health insurance program for people with low incomes or disabilities, pay for navigators to help patients transition from detoxification programs into alcohol treatment. Many Native Americans don’t make that jump successfully.

Researchers at the Johns Hopkins University Center for American Indian Health underscored the importance of home visiting programs. These connect expecting mothers with Indigenous clinicians and have been shown to prevent maternal substance use and reduce adverse childhood experiences.

Dr. Jennie Wei, an addiction specialist at Gallup Indian Medical Center, emphasized screening and treating Native peoples for mental health disorders such as depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and historical trauma, which many patients cope with by drinking. “If we don’t make this a priority, alcohol will continue to be the main treatment.”

People have divergent views about how to address the availability of alcohol near reservations. Kamilla Venner, an associate professor of psychology at the University of New Mexico who is of the Ahtna Athabascan in Alaska, suggested the state work with tribal governments to identify alcohol outlets that exploit proximity to the reservations for commercial gain, and look into closing them.

In contrast, Democratic state senator Benny Shendo of Jemez Pueblo wondered if reservations should drop their restrictions on alcohol consumption. “That way, people can be drinking in their own homes, instead of trying to sneak something in or going off through border reservations and so forth.”

Both views speak to the challenges of moderating drinking in border-towns like Gallup, where criminalizing alcohol can create stigma and foster abnormal habits but where unrestrained flows feed existing addictions.

Make counseling and medications for alcohol disorders universal: Primary care doctors can play a crucial role identifying harmful drinking behaviors, counseling their patients to cut back, and prescribing medications and other services to help them do it. New Mexican doctors are not living up to this responsibility.

Professional associations and teaching institutions could prioritize the diagnosis and treatment of alcohol disorders in their educational efforts.

Gallup Indian Medical Center has shown that with thoughtful protocols, investments in appropriate staff, and sustained leadership, a healthcare organization can radically increase counseling for alcohol disorders and use of medications such as naltrexone. Every medical institution in the state could embrace similar practices.

6. Address the number of businesses that sell alcohol

For more than 70 years, New Mexican law has limited the number of businesses licensed to sell alcohol in any given municipality or county to one per 2,000 people — but the law has never had many teeth. In communities that already exceed their cap, such as Albuquerque and Santa Fe and the towns of Gallup, Farmington, and Española, the state does not issue new licenses — but existing license holders can re-sell them to others. In effect, the law does nothing to diminish the profusion of alcohol businesses.

Shelley Mann-Lev, former president of the New Mexico Public Health Association, said the state’s Regulation and Licensing Division could establish clearer limitations on areas where alcohol businesses are restricted, with an efficient process for localities to assess potential businesses’ impact on safety.

In Baltimore, Maryland, which for decades had alcohol outlets in excess of a limit dictated by state law, a 2017 zoning rewrite barred most outlets from locations within 300 feet of each other, and required outlets out of conformance with the law to relocate or stop selling alcohol. Although alcohol sellers fought the change, researchers believe it could profoundly reshape the city.

Applying this to New Mexico, Mann-Lev said the Division could extend the distance around certain sensitive spaces like schools and places of worship where alcohol sales are prohibited and add other categories of facilities, such as supportive housing and licensed childcare centers. It could also require alcohol outlets to be at least 1,000 feet from another, breaking up dense concentrations. Colorado enacted similar legislation in 2016, prohibiting new retail liquor licensees to locate within 1,500 feet of existing licensees, and within 3,000 feet in more sparsely populated areas.

7. Limit alcohol ads that target youth

Globally, the alcohol industry spends billions of dollars each year marketing its products, and youth absorb many of those messages. That’s dangerous because early initiation of drinking is a significant risk factor for addiction later in life.

Data from Kantar Group, a firm that monitors advertising spending, showed that just four brands — Michelob, Miller, Coors, and Budweiser — spent $982,000 on marketing in New Mexico in the year ending in May 2022. This estimate does not include national or digital ads that also reached New Mexican audiences, nor marketing to bars and restaurants themselves, which can be substantial. An advertising executive who spoke on condition of anonymity said one of her former clients, a major liquor producer, spent half its advertising budget promoting itself to retailers.

Some states have attempted to limit alcohol advertising by prohibiting false or misleading ads and restricting outdoor ads on college campuses and in locations where children are likely to be present. They also have given alcohol control agencies jurisdiction over electronic media. New Mexico has no such laws.

Redefining responsible drinking

Curbing alcohol-related deaths in New Mexico will also require a fundamental shift in the state’s drinking culture.

Many people quoted in this series drink alcohol, as does its author. None suggested prohibiting alcohol was realistic, reasonable, or required — although the science is increasingly clear that drinking confers no health benefits, and imposes increasing risk as a person consumes more than one drink per day.

But without a broad reduction in alcohol consumption, New Mexico’s surging alcohol-related death rate will continue to rise, dragging on the state’s economy, perpetuating violence and trauma, and shattering tens of thousands of additional families.

The meaning of a ‘responsible drinker’ has evolved over time. Where once it signified consuming in sufficient moderation to manage the tasks of daily life, it has grown to include a responsibility for fellow drinkers, too: after all, friends don’t let friends drive drunk.

It is past time for a further evolution, to an understanding that responsible drinking also means cultivating a shared drinking environment — even if it asks sacrifices by some — that is safe for everyone.

Long-time alcohol sellers say they already practice this philosophy. Tasha Zonski-Armijo, the third-generation of her family to run Jubilation Wine & Spirits in Albuquerque, said that she would not want to profit from a single transaction that leads to harm. “No sale is that important.”

Brewer Jeff Erway recalled a regular from his tap-room who abruptly disappeared; months later the man stopped by to explain he’d been spending more time with his mom and decided to quit drinking. He’d lost weight and looked great, and Erway couldn’t help but feel relief. “I’ve lost a customer — but of course I am happy for him.”

Maurice Bonal isn’t giving up his role as the state’s leading broker of liquor licenses any time soon, but he gave up drinking long ago. “At some point in my life, I was a better customer than an owner,” he said, a hazard he has observed among many other license holders. He has different aspirations for his own children. “I don’t want ‘em in this business.”

These days, the alcohol lobbyist Ruben Baca said the most he’ll partake in is a half glass of wine. “As far as drinking, forget it,” he said.

“It’s not good for your health.”

Download this article as a PDF.

Help New Mexico In Depth better understand alcohol’s role in the state by sharing your story.

Ted Alcorn is a writer raised in New Mexico whose work has appeared in The New York Times, The Atlantic, and The Washington Post Magazine, among other publications. For New Mexico In Depth he’s investigated how the state’s prisons have ignored an epidemic of hepatitis C, how Albuquerque stood up its branch of non-police emergency response, and how non-profit hospitals shortchange community health. Follow him at @tedalcorn.