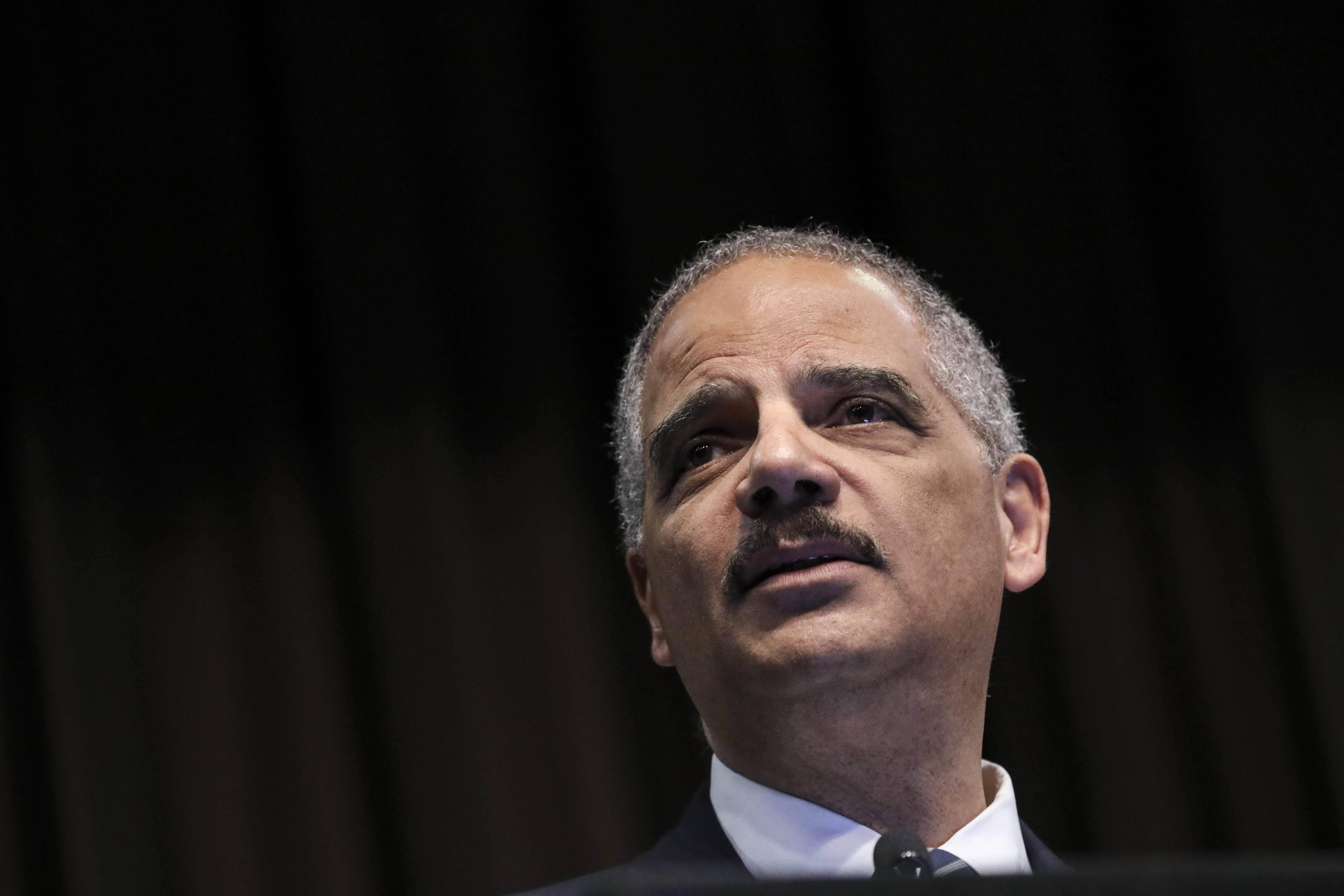

On the latest episode of Amicus, Dahlia Lithwick spoke with former U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder about his recent book, Our Unfinished March, which discusses how voting rights have been broken and offers a plan for restoring our democratic institutions. In the following excerpt from the episode, Lithwick and Holder discuss a private protest that Holder explained more fully in the book.

Dahlia Lithwick: Can I ask you about one part that really broke my heart? You describe, partway through the book, your own “silent protest” after Shelby County comes down. It’s always been the case that the attorney general symbolically argues one case at the Supreme Court. And usually it’s an easy lift, but it’s important and symbolic. And you say that after Shelby, you just couldn’t do it. You wrote: “I didn’t want to pretend that this was a Supreme Court like any other, that the justices were good faith actors, that a tradition should be followed. They had without legitimate basis undermined our most fundamental right. A right that Americans of past generations, some of whom looked like me, had died to secure the right to vote.”

And then you say, “This was a silent protest.” You hadn’t told people till now that you would not appear before that court as the AG of the United States. Wow. There’s so much in there that I want to ask you about. But I think at the heart of what you’re saying is: I love this institution. I revere this institution. As a young attorney, this was a temple of sorts for you. And then once it was so fundamentally enshrining something that, particularly as a Black man, you could not abide, you just couldn’t participate in giving cover to the idea that it’s legitimate. That’s so complicated. And I wanted to give you a minute to think about it out loud.

Eric Holder: Yeah, it is complicated. And the book describes the transition that the young Eric goes through to get to where Attorney General Holder ended up. Because my first trip to Washington, D.C., was as a first-year intern. I just completed my first year of law school. I was working at the NAACP Legal Defense Fund and was tasked with the enormous responsibility of getting on the Eastern shuttle, flying from New York to Washington, going to the Supreme Court Clerk’s Office, and just filing something.

It was my first trip to Washington, and I walked into the Supreme Court. They gave me a bunch of pamphlets, and it described who was on the court. I remember standing on the steps of the court, looking at the Capitol. I’d never been to Washington, D.C., before. I’d seen everything on my little black and white TV in Queens, and now I’m seeing everything in color and it became real. I could see off in the distance where Dr. King gave his speech in 1963 at the March on Washington. I’m in the Supreme Court. I’m looking at Congress.

It was, for me—even though I knew the Supreme Court had not gotten everything right, even up to that point—a breathtaking experience for me. And I remember how charged up I felt on that plane ride back from Washington to New York.

And then you fast-forward to the attorney general of the United States. It’s just as you say. I watched Janet Reno, when I was deputy attorney general, prepare for her argument and being assured over and over and over again, There’s no way you’re going to lose this case. This is the easiest case we’re going to have to argue. It’s important symbolically for you to interact with the justices. Every attorney general does it.

And so I decided I wouldn’t do it in the first term because I just thought whatever I say up there on whatever case will somehow get misconstrued. I don’t want to have the White House mad at me for having some negative impact on Barack’s reelection efforts. I’ll do it in the second term. And then Shelby County comes down.

After Shelby County, I felt that if I were to go there as the first African American attorney general, as if this abomination of a case had not occurred, that my people were not negatively impacted by what it is that five of these justices had done. I said, “No, I’m not going to do that. I’m not going to just say this is business as usual.”

Now, I didn’t make a big deal of it. I could have announced ‘I’m not going to go and argue a case’ for the reasons I’ve just outlined. But I said, “I’m not going to participate. I’m just not going to go up there and at least put a veneer on what my feelings are,” which was I was distraught. I was angry. I was very troubled by what the court had done in the Shelby County case. And I call it the Shelby County case, but it’s more appropriately Shelby County v. Holder. And that’s something that to this day disturbs me. The notion that my name is associated with the case that eviscerated the crown jewel of the civil rights movement.

Ultimately, I decided no matter how easy the case, no matter what the tradition, the most important thing that this Black man could do would be not to participate in a process that had led to, or was in the process of leading to, the evisceration of the thing that had most helped my people during the course of our stay in this nation. The right to vote is what made me attorney general. The right to vote is what lifted my people out of poverty. The right to vote is the thing that has protected the lives of Black Americans through the course of the history of this nation.

And so this Black man was not going to stand before the Supreme Court and say, “I’m here to win an easy case.” I’m not going to do that. But I wanted to, at some point, make clear why I did what I did or why I didn’t do what people expected me to do. And this book gave me the opportunity to explain it.

The reason it’s so painful to hear you talk about it for me is that I, in a much smaller scale after the Kavanaugh hearings and as a woman who sat in the chamber during the Kavanaugh hearings, had the same experience where I just had to stop going into the Supreme Court. And for a long time, it was a secret protest, as was yours. It took me a long time to write about why I couldn’t go in the room. But what I love about what you’re saying and what I hear in what you’re saying is that this is a function of adoring this institution. Not hating this institution.

Right.

This is an institution that gave us Brown. This is an institution that gave us Griswold and Casey and Cooper v. Aaron. And it is not from a place of pique. It is from a place of I don’t know how to hold the idea in my head that it is both lofty and broken. And that’s what these protests are about is not wanting to participate in saying that the thing that is now broken is still lofty.

But for me, it just was very powerful to read it. The book literally has a checklist of stuff people can be doing right now about gerrymandering, about the Electoral College, about fixing the Senate, about doing away with the filibuster. Ultimately this is a show about the Supreme Court, so I need to give you a chance to talk about your notions about how to fix this Supreme Court that you could not bring yourself to argue in front of.

And you’ve got a couple of suggestions, and I just want you to talk about them, in no small part, because we seem to be in a moment where everybody, again, feels as though there is nothing to be done. The court is the court and the court is made of magic, and we all have to exceed to that reality. You have some simple fixes, simple and constitutional fixes.

And they come from a place, to echo what you said, a place of love, from a desire to have an institution that I revere or have revered return to the place where I think it should be. I think we should reduce the amount of time that people serve on the court. Lifetime appointments, when made at the beginning part of the republic, made sense. It insulated people from political pressure. People didn’t live nearly as long as they do now so they didn’t serve nearly as long as they do now. People also left the court in the early parts of the republic, not making a determination about who would appoint their successor, but simply because they died.

And this is one of the places where the chief justice and I, as I point out in the book, tend to agree. I think we should have 18-year terms. He says 15-year terms. But I think to have people serving on the Supreme court for 30, sometimes close to 40, years, in an unelected position, that gives a person too much power. People serve in Congress and in the Senate for extended periods of time. But at the very least, there’s at least nominally a check that the American people have on that power by voting for them or voting them out.

The Supreme Court, they’re looking for early 50s, late 40-year-olds, so that they will serve for, again, 30, 40 years, which is not to take any shots at any of the people who are on the court. But 15–18 year terms makes a great deal of sense. I like 18 because that goes along with my other proposal, which is that every president in his or her term should in the first year appoint a Supreme Court justice and in the third year appoint a Supreme Court justice. And if you have 18-year terms, over time, you will get to a court that gets back to nine members.

Because the other thing that I say we have to do is expand the court to deal with the way in which it was politicized by Mitch McConnell and his Republican conspirators, by telling Merrick Garland you can’t get a hearing because it’s too close to an election. And then putting Amy Coney Barrett on the court while people were in the process of voting. The American people understand that was not right. That was not appropriate. What people don’t understand is the impact that had. This would be a court now that would have a 5–4 progressive democratically appointed majority.

And so, the Rucho case, where the Supreme Court said, We’re not going to deal with partisan gerrymandering, probably would’ve been decided in a different way. The Janus case that dealt with union power would’ve probably been decided in a different way. There’s a whole range of cases from the time Merrick Garland would’ve gone on the court until now, and then continuing with somebody different than Amy Coney Barrett being appointed by President Joe Biden that would have transformed the court. We would not have had to deal with the whole question of Roe v. Wade. That court would not have had to deal with what the court did.

So there’s a whole variety of things in a very practical way that these suggestions that I’m making. A lot of people are going to say, “You’re talking about the House, the Senate, the Supreme Court, the presidency, voting. That’s impossible. How are you going to do that?” But that’s the point of the book. We have made substantial changes before, changes that seemed impossible, obstacles that seemed insurmountable. And the American people energized, focused, committed, prepared to sacrifice, brought those changes about.

And it is during those times when America has shown that it’s in fact an exceptional nation, when we end slavery, when we end Jim Crow, when we make sure that women have the right to vote, when we pass a voting rights act so that we eliminate poll taxes, literacy tests. All of these things, that’s when this nation shows itself to be great. And we can do it once again.

People underestimate the power that we have as so-called ordinary citizens. We have within ourselves the power to do extraordinary things. I hope people will come away from [the book] feeling a sense of optimism and a renewed sense of commitment.