Claes Oldenburg, the pop artist who reimagined everyday objects like clothespins and spoons as mammoth sculptures, has died at age 93, according to Pace Gallery in New York, which has represented the artist since 1960. Oldenburg had recently suffered a fall and died Monday in his home and studio in New York City, the gallery said.

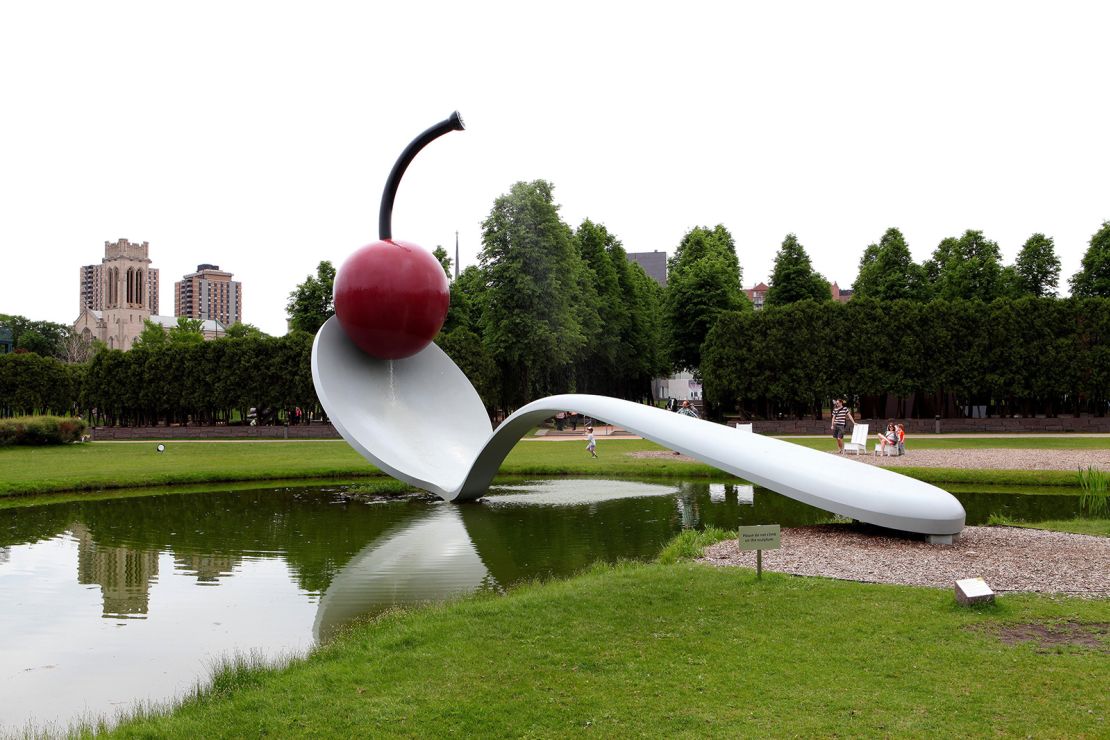

The Swedish-born American sculptor was a key figure in New York’s art scene in the 1950s and ’60s, first in performance art before becoming a definitive figure of the pop art movement alongside artists like Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein. He was known for his soft cloth or foam-rubber sculptures of pastries, cakes and cheeseburgers, as well as colossal works made in collaboration with his late wife, Coosje van Bruggen.

The couple married in 1977 and worked together for over three decades, producing iconic sculptures outside of art museums across the US, including a giant dustpan and brush at the Denver Art Museum and shuttlecock at the the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Missouri, as well as at other spaces for public art. The duo also collaborated with famed architect Frank Gehry to blur the lines between architecture and sculpture – in 1991, they incorporated a binocular-shaped structure into Gehry’s building for the Chiat/Day agency in Los Angeles.

Van Bruggen died in 2009 after being diagnosed with breast cancer.

Arne Glimcher, founder of Pace Gallery, called Oldenburg “one of the most radical artists of the 20th century.”

“In addition to his inextricable role in the development of pop art, he changed the very nature of sculpture from hard to soft, and his influence can be seen to this day,” he said in an emailed statement to CNN.

Oldenburg executed one of his pivotal early pop art works, “The Store” in the winter of 1961, creating replicas of all of the objects inside a rented Lower East Side storefront – sculptures of undergarments, sandwiches and pie, as well as a cash register and fake business cards.

“One rule about my work is that it must not have any function,” he is quoted as saying in a video from the Museum of Modern Art about the influential installation. “It must be completely form. I begin by removing the function of the thing, because its true function is to become an artwork.”

In 2020, the artist Hank Willis Thomas, known for his conceptual and civic artworks around the country, acknowledged the influence of Oldenburg on his own public art in an essay for CNN Style, saying the pop artist “could take any quotidian object, such as a garden spade or badminton birdie, and monumentalize it.”

Oldenburg’s famed sculpture of a clothespin in Philadelphia was on his mind, Thomas said, as he designed a giant afro pick with a raised fist, titled “All Power to All People,” in 2017 for the city.

Paula Cooper, who also represented Oldenburg’s work through her eponymous New York gallery, said over email that artists have long been informed by the sculptor’s “freedom of thought” and that his work only became “grander and bolder” when he married Van Bruggen.

In 2000, Oldenburg was honored with the National Medal of Arts alongside Barbra Streisand, Maya Angelou and Chuck Close, among others, selected by former President Bill Clinton from a group of nominees chosen by the National Council on the Arts.

Over the decades, Oldenburg mounted solo exhibitions and retrospectives at major institutions including the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. In 2021, Pace Gallery produced the artist’s last show: an exhibition featuring Oldenburg and Van Bruggen’s final work together, “Dropped Bouquet,” which they conceived together toward the end of her life, according to the gallery. The giant aluminum sculpture of a handful of flowers upside-down on the floor was initially planned for the Indianapolis Museum of Art’s sculpture garden but wasn’t realized until last year.