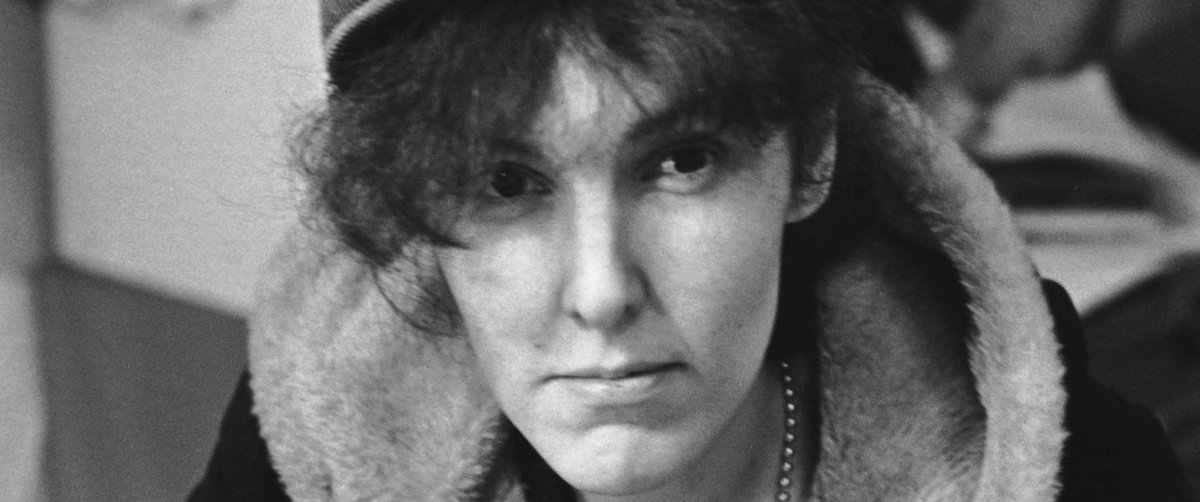

For a while there, I became obsessed with Valerie Solanas’s SCUM Manifesto. How can one not, with this opening line?

Life in this society being, at best, an utter bore and no aspect of society being at all relevant to women, there remains to civic-minded, responsible, thrill-seeking females only to overthrow the government, eliminate the money system, institute complete automation, and destroy the male sex.

This extraordinary opening sentence starts in a mood of studied nonchalance, its participle “being” introducing as a given something which may in fact require argument. It is a sentence which starts in a distinctly camp mode, conjuring a cocktail-party wit—leaning on a bar perhaps—but which, by the time it becomes declarative, swerves to a stark, deadpan seriousness. It showcases Solanas’s intense penchant for lists, here enumerating casually asserted yet wildly ambitious demands. It displays an impeccable sense of rhythm and comedic timing, the final devastating words landing with an almost shoulder-shrugging obnoxiousness. The manifesto’s egregious unreasonableness turns on the word “only” in that perfect first sentence. I laughed out loud in a library on first reading.

I’m not sure Solanas intended the manifesto to be funny. Jeremiah Newton, a 17-year-old boy who turned up for auditions for her play, Up Your Ass, has said that “she wasn’t a comedian by any stretch. Just the fact that she was so serious made her funny.” Seriousness and impatience are key to the manifesto. In an interview in the Village Voice in 1967, Solanas answered Robert Marmorstein, who had asked if she was “serious about the SCUM thing,” by saying “Christ! Of course I’m serious. I’m dead serious.”

Pressed on why peaceful revolution wasn’t possible, she said “we’re impatient”; “I’m not going to be around 100 years from now. I want a piece of a groovy world myself. That peaceful shit is for the birds.” Vivian Gornick has rightly described Solanas’s voice as a voice “beyond reason, beyond negotiation,” but in this disarming statement of desire—I want a piece of a groovy world myself—we glimpse also the longing and perhaps the deprivation that might underlie it.

SCUM Manifesto is tremendous, an awe-inspiring, thrilling piece of writing. It has an urgency and a rage in dialogue with a ludic enjoyment in pure language, as if Solanas has been carried on a wave of her own linguistic capacity and is having a wild ride. It baldly aims to bring forth a future that she makes sound utterly reasonable. She is perennially irritated by others’ slowness, their failure to have reached the self-evident conclusions that she has. Things are very clear for her; hallucinatorily sharp and obvious. It’s uncanny to read; it’s both objectionable and lucid, lucid to the point of being a lurid fantasy.

Amongst much else, she advocates membership of the “unwork force, the fuck-up force,” elaborating arguments for automation that have since flourished in left discourse; she shruggingly asserts assisted reproduction as a self-evident inevitability; she dissects what some might now call emotional labor; she anticipates the ubiquitous surveillance that we’re now in thrall to, as well as a “perpetual hardness technique” (such as Viagra).

And all this from the gutter, from a precarious, hand-to-mouth existence on the streets of New York, in 1967, its author hawking her mimeographed pamphlet—one of the most searing, brilliant, grandiose feminist texts ever written—around town in an increasingly desperate state.

*

Daddy Issues, my short book about fathers and daughters, emerged in part from the phenomenon of #MeToo; the anguished, rageful reckoning with violence against women that swept through the media in 2017 and 2018. #MeToo elicited plentiful metaphors of beginnings and endings, of tsunamis washing shame away, of wrongdoings being exposed to the light of day and of truth, of a cleansing and a destruction all at once.

Bad men—boyfriends, sexual partners, and bosses in particular—were subjected to intense scrutiny. But fathers seemed to be largely absent from the rhetoric that swirled, and from the remarkable rise in prominence of feminism in the last ten years. Was this the familiar insulation of the private realm, the family, from scrutiny? Had feminism forgotten about fathers?

Could I, I wondered, derive some kind of wicked pleasure from dashing off a text that simply leaned into my own hostility, in a perhaps unreasonable, deadpan way?Daddy Issues also emerged from a fascination I’d long had with that phrase—”daddy issues”; a phrase routinely, knowingly, casually thrown out about a woman’s sexual choices. It is usually invoked to mock a woman for choosing a man who can be construed as a version of her father—by virtue of his age, status, or power. It nods to the power of the father and the patriarch—but then laughs at a woman for being in thrall to these. It fleetingly sees something clearly, but then turns on the woman. It serves to deflect attention and locate in the other—the woman, the girl—dynamics that are interrelational, social, and political.

The phrase also takes as a given, and then scorns, the possibility that our lives and our sexual desires are profoundly shaped by our relationships to our parents or caregivers. This terrain—infantile sexuality, Oedipal desires—often induces a phobic shudder. The phrase “daddy issues” curiously acknowledges this terrain, however, only to then reject it, turning it into a source of derision, at the cost of the women, who, as its target, are asked to be accountable for their sexual and romantic choices.

This is a familiar dynamic: the disproportionate spotlighting of women’s responsibility for sexual relations. A dynamic which, incidentally or not, is what #MeToo was trying—often clumsily, unsteadily—to address and possibly invert. Some—not all—of the disquiet about #MeToo may come from a feeling that simply inverting this structure—turning the spotlight around and interrogating male sexuality—may not be the self-evident solution that it can be felt to be.

But in Daddy Issues, I wanted to explore how representations of fathers and daughters—in fiction, in film, on TV, in public families—do a tremendous amount of work, teaching us lessons in gender and in heterosexuality, while also revealing and reinscribing an enduring horror at female sexuality—particularly a girl’s emerging sexuality. What happens when we look more closely at “daughter issues”—those of fathers and of the culture more widely?

*

Daddy Issues was a flight of fancy—a format in which I could write something short and fast, without thinking too much about it. Partly this was of necessity; it was commissioned, and by the time I found time for it, I had to squeeze the writing into busy days, writing bits here and there, and not having time to get too self-conscious about it. It came from a place of anger, sadness, unresolved difficulty, but it felt joyous to write. Could I, I wondered, derive some kind of wicked pleasure from dashing off a text that simply leaned into my own hostility, in a perhaps unreasonable, deadpan way? I don’t think Daddy Issues reads at all like SCUM Manifesto, but I know it was there, hovering, with its rage and violence, in my dark little book about dads.

Joanne Steele, a key figure in the emerging women’s movement of the 60s and 70s, has said that SCUM Manifesto “had an important message for women to hear. Nothing else was as virulent. She was the first to say you can hate your oppressor.” This is key. Solanas embraced her feelings of hate; not just a noble feeling of anger about injustice, but a feeling of pure hatred and disgust. Not just for men, either. All women “have a fink streak about them,” she notes, that stems from “a lifetime of living amongst men.” And she is caustic about “passive, rattle-headed Daddy’s Girl, ever eager for approval, for a pat on the head, for the ‘respect’ of any passing piece of garbage, is easily reduced to Mama, mindless ministrator to physical needs, soother of the weary, apey brow, booster of the tiny, appreciator of contemptible, a hot water bottle with tits.” No one escapes Solanas’s acerbic ire.

When I see women posting on Father’s Day about their dads, it’s possible that I feel some envy, but also some shame, too, about having much more mixed feelings than many of these posts convey. And yet mixed feelings—ambivalence—are the natural state of things, from the day we are born. Mothers, fathers, caregivers provide but also frustrate, and they have to, if they are to provide the conditions for their infants’ development. Aggression and hatred are an inevitable and necessary part of development for infants, and create the possibility for so much else, including love.

Donald Winnicott argued that the child needs to hate and defy someone, without there being a complete rupture in the relationship, in order to develop a sense of self. Adam Phillips has written of the requirement on parents to be both “sufficiently resilient and responsive” to be able to “withstand the full blast of the primitive love impulse”; the full blast that includes aggression. That’s what this little book felt like to me: a blast of aggression that it felt important, and pleasurable, for me to give voice to. Could I be ruthless, as Winnicott argues the baby needs to be in relation to its caregivers?

Solanas took a refusal of deference towards men to a mad, thrilling extent. Was I doing something similar, digging my heels in and refusing any concession of warmth to fathers? Could I write a book about fathers that could play with my own aggression—my need for aggression—and come out safely on the other side? I was diving in, perhaps, to my difficult feelings in the hope that really reckoning with them might be transformative. Writing Daddy Issues was, I think now, an experiment in attempting to destroy an object who could, hopefully, survive that destruction. It was an attempt, in Winnicott’s terms, to feel real.

*

The obvious problem with SCUM Manifesto is that Solanas made good on her promises. She shot Andy Warhol, who survived, but only just. How does one read a book about destroying the male sex when you know the author tried to kill a man and irreparably changed his life? Solanas had been on the periperhy of Warhol’s Factory, Solanas, and she had interested him—he cast her in I, A Man. But then he lost interest and also lost her play. They were both outsiders, Catholics from blue-collar immigrant families, but for Solanas, Warhol (along with her publisher Maurice Girodias) became a metaphor for deception, withholding, and profit—a figure of paranoia.

Yet, as Breanne Fahs argues in her book on Solanas, “Valerie exhibited a unique blend of schizophrenic paranoia and outright accuracy.” Kate Millett has said that “even people who respected Warhol and his work thought that people at the Factory were being used as cannon fodder for avant-garde art.” As Olivia Laing has written of Solanas, “just because you’re paranoid doesn’t mean they’re not out to get you.” Solanas was excluded and quite possibly ill-treated, not just by the worlds she gravitated towards in New York, but in her volatile early life too. She lived an errant and erratic life that included imprisonment and hospitalization, and died aged 52, her body having been left several days before she was found.

Plenty have found SCUM Manifesto more objectionable than anything else, though plenty of writers (Andrea Long Chu, Breanne Fahs, Avitall Ronell, Olivia Laing) have, like me, been enthralled and thrilled by Solanas’s writing. It feels genuinely alarming to read her, disquieting to love this “indefensible text,” as Ronell puts it. But as Ronell goes on to say, “psychosis often catches fire from a spark in the real.”

Solanas had a lot, still has a lot, to teach us. As for Daddy Issues, any violence there was safely contained in a long essay, steadied by the forces of sentence-making. Though I might have felt alarmed writing it, I guess it worked out fine. Everybody survived.

TEXTS

Andrea Long Chu: “On Liking Women,” n+1 30, Winter 2018 · Olivia Laing, The Lonely City (Picador, 2016) · Breanne Fahs, Valerie Solanas: The Defiant Life of the Woman who Wrote SCUM (and Shot Andy Warhol) (Feminist Press, 2014) · Avitall Ronell, “Deviant Payback: The Aims of Valerie Solanas,” introduction to SCUM Manifesto (Verso, 2004, 2015)

__________________________________

Daddy Issues: Love and Hate in the Time of Patriarchy by Katherine Angel is available via Verso Books.