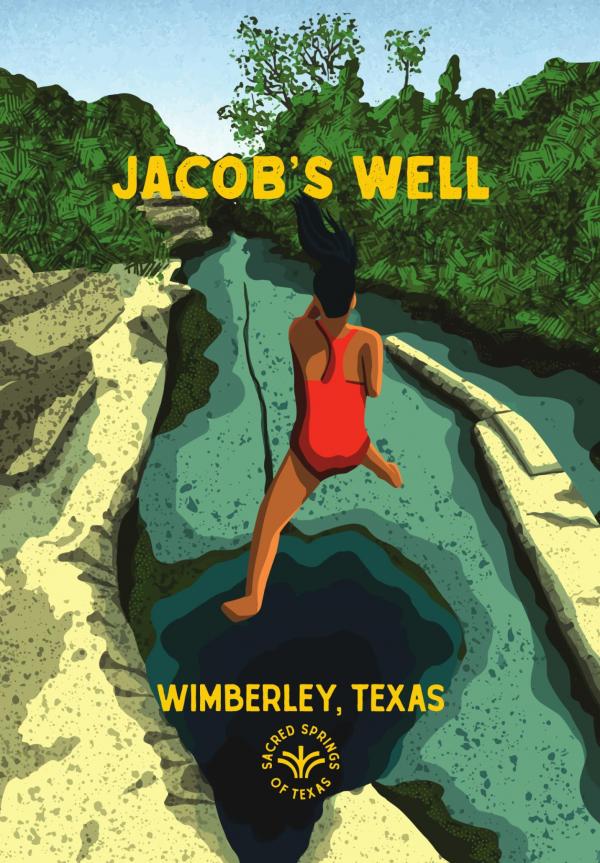

DIVING INTO JACOB’S WELL

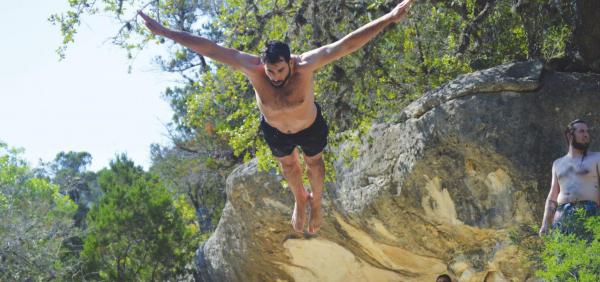

The anticipation is almost too much to bear, but it may not just be the height of the jump that causes your adrenaline to pump. It’s also the knowledge that the 68-degree water is waiting below to shock every sense in your body as the heat of a 100-degree day vanishes from your skin.

Even though your body is telling you not to, you jump anyway from the rock outcrop above.

By the time your toes hit the water, you know if you’ve landed in the 30-foot-deep mouth of Jacob’s Well as the chill tingles up your body. Eventually, your head is dunked under as you plunge beneath the surface only to look up at the sun shining through the gaping hole now above you.

It’s a Wimberley baptism.

For many residents, swimming and diving into Jacob’s Well seems like a rite of passage.

Being documented since the 1930s, Jacob’s Well has seen many people for nearly 100 years come to the spring to jump from the rocks into the cold, clear waters below.

Over the years, a few rules and regulations have been added, but it is still a popular place to visit with locals still reminiscing about their time.

For long-time Wimberley resident Tracy Sites, she still has the memories of when her grandfather would take her and his other granddaughters to the well.

“Cousins, the Ross’ had a cabin just downstream from the well,” Sites said. “We would wade up to it, climb the rocks, and jump in! Favorite memories!”

For Austin Vaughan, it was grabbing the pebbles at the bottom of the first chamber of Jacob’s Well about 30 feet below the water’s surface.

“Making it to the bottom of the well in one breath for the first time,” Vaughan said. “That is a memory that sticks with me.”

There were tales of the Texan football team using the cold well water in place of an after-practice ice bath and even stories of finding true love.

“This is also where my wife and I had our first date,” Bryan Buse said. “We skipped fourth period English and went to Jacob’s Well to soak in the sun and cool off in the water. Of course we were busted, so our second ‘date’ was (In School Suspension) together the next day.”

Others told of how kids were scared to swim across the well fearing that the well itself would pull an unsuspecting swimmer down under.

“(Joy Lane) had been in Wimberley since she was a young child,” Mary Van Ostrand said, recounting a story that Lane, who passed away last year at age 93, had told her. “...She told me that she and her friends were afraid to swim across the hole at Jacob’s Well because it might pull them down into it.”

Fortunately, that myth is long debunked as there is no evidence that the Jacob’s Well actually pulls swimmers down under although there are a number of scuba divers who may disagree. At least eight people have lost their lives scuba diving in Jacob’s Well.

The myths do not deter the locals nor do they deter visitors who enjoy the well that is now a public natural area owned by Hays County.

“It’s refreshing,” Zach Shunk, who was visiting from New Mexico, said. “But you really don’t feel it, because of the adrenaline. So the temperature is not really a thing. It’s more of the shock of not hitting the rocks.”

The well is only a few meters wide and is a strikingly perfect cylinder diving down deep into the water almost as if it were made by man. At the top, the water spills out to form the headwaters of Cypress Creek at a depth about waist high as the water sits behind a small dam. It narrow quarters and perfect depth make for a natural set of bleachers for the sixty or so swimmers allowed in at a time.

“I’ve only been here for a couple of weeks, so I’m trying to hit all the springs here,” Shunk continued. “This one is really unique. It’s small, but the unique feature is the depth of the cave. So my expectation was different. I thought it was going to be something like a Barton Springs type swimming hole, but it’s more of a focal point of something. It’s weird, but in a fun nostalgic way of having everyone sitting around and cheering the people who jump in. I wasn’t expecting that, but it was fun.”

Heath Theriot, who was also jumping into Jacob’s Well for the first time, had a similar experience.

“It was refreshing,” Theriot said. “I thought I was going to be uncomfortable, but once you jump in it it’s not bad at all.”

“I think it’s neat,” Theriot said. “It’s a pretty cool way to use a public space.”

But what is the cause of the unique identity of Jacob’s Well?

The answer starts millions of years ago when the Balcones Fault Zone was active.

“Paralleling I-35 towards the entire region up towards Dallas is the Balcones Fault Zone,” Katherine Sturdivant, who runs the Education and Outreach program at the Jacob’s Well Natural Area. “That is why it is really flat on the east and hilly on the west. When the Balcones Fault Zone was active, it created a big uplift in this area, which is why we have this topography. Similar to punching a window, you have these little spider webbing fractures that come out from the point of impact. You can see this small (fault) line running just below the well, which is probably one of those fractures.”

Because of this fracture, rainwater had started to seep into the ground to create an underwater reservoir or aquifer. However with the rainwater flowing underground, it needed a place to go. It found the fault line that runs next to Jacob’s Well.

“This fracture was originally created in the limestone bedrock about 30 million years ago, we suspect,” Sturdivant said. “After that point, once this ground was highly fractured, rainwater was able to start percolating down into the ground where it was held in reservoirs. Water is always trying to move around and is looking for a place to go so it starts trickling through whatever way it could. Eventually a line of water probably made its way through some sort of crack or fracture in the bedrock and started up this fracture here.”

The effects of the water erosion over millions of years eventually created the now famous well as it is known today.

“Over millions and millions of years that water erosion was so strong that it carved out a cave system and this 12-foot-in-diameter hole in the ground,” Sturdivant said. “It is still eroding incredibly slowly, which means we will never see any changes in our lifetime, but it will continue to grow over the millions of years if we still have water flowing through it. If not, it will become dry and become a dry cave at some point.”

As Sturdivant has found, it can be difficult to protect the well from damage.

“It is very difficult, but we walk a fine line of being recreation and conservation,” Sturdivant said. “For a little over half of a year, we are in an aquatic restoration period where we keep everybody out of the water, so everything can revegate and regrow. For the five months of the year, we allow swimming in the well. It is the best balance we are able to strike, which allows us to protect the well for half of the year, and then let people swim in it half of the year.”

“We did try to open the park and not let people swim here at first, but we found out that was nearly impossible,” Sturdivant continued. “What I personally found was that when people come out here and have a fun or positive experience, it tends to establish a little bit more respect for this site. They come out and have a nice time and enjoy the beautiful scenery, and it motivates them to feel protective of the spring in future times.”

As both locals and visitors continue to visit and swim at Jacob’s Well, Sturdivant found out the benefits of letting people enjoy the once-in-a-lifetime experience of diving into Jacob’s Well.

“I think letting people swim here is probably necessary to protect it because it gives people something they want to protect.”

Wimberley’s history, beauty and lore are intertwined with the cold, deep waters that spring forth from the aquifer below and bless this region with Cypress Creek. This is the second of a four part series looking at the historical, cultural and environmental impacts created by diving into Jacob’s Well.

“This one is really unique. It’s small, but the unique feature is the depth of the cave... It’s weird, but in a fun nostalgic way of having everyone sitting around and cheering the people who jump in. I wasn’t expecting that, but it was fun.”

Jacob’s Well Swimmer Zach Shunk