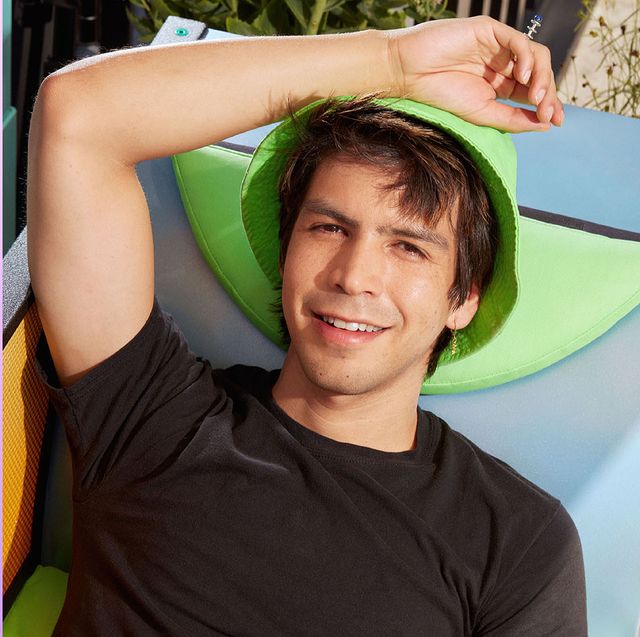

Welcome to So Courant!, deputy editor Sean Santiago’s column spotlighting emerging makers, the newest launches, and the latest design destinations in the world of ELLE DECOR. This week, comedian Julio Torres caps off Pride Month with a chat about his unique taste, his take on trends, and the design tics he inherited from his parents.

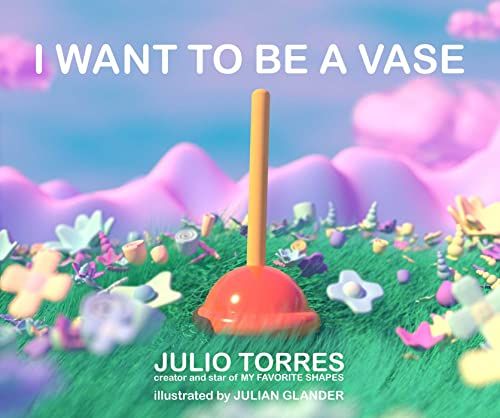

Julio Torres may be best known for his starring role in HBO’s Spanish-language comedy Los Espookys, or perhaps his hourlong special about shapes on that same network, aptly titled My Favorite Shapes. But the former Saturday Night Live writer’s new children’s book, I Want to Be a Vase (Simon & Schuster)—about a plunger that dreams of becoming a vase—proves that Torres has a particular knack for working out complex issues of class and identity through humor. I was determined to find out why.

ELLE DECOR: What made you want to write this book as the next shape-related content from your universe?

Julio Torres: Uplifting stories are obsessed with the idea of the protagonist and the individual, and I wanted to complicate that a bit more. I wanted to show that Plunger is not actually special or unique, but that every object around him has their own special desires. I also wanted to confront the naysayer—the vacuum cleaner—and welcome that voice into the conversation as opposed to banishing it. I was very into exploring the context of the individual.

ED: And it’s intriguing to do that through household objects, which are easily grouped—kitchen things versus bathroom things, for example. What was the process of choosing and isolating these different elements of the home for this story?

JT: Objects are designed to serve a purpose, and that really made me think of human labor. One of the first things people ask each other is, What do you do? We’re asking, Are you in the bathroom, or are you in the kitchen? And really that informs how we engage with each other and what we want from each other and the validity of ourselves. I was very interested in having a children’s book that broke that, where the objects have autonomy despite the fact that they were made with a specific purpose in mind, or that their shape, their form, would suggest that they’re only equipped to do one thing. It’s interesting because there is a queer reading to be obtained from the book—which I think is the dominant reading—but to me it’s also a book about labor and class.

ED: Which are recurring themes in your work. You mention in My Favorite Shapes the dividing curtains between first class and economy, and this idea of how the object creates and reinforces these divisions. Are you big on organization and categorization?

JT: No, I’m not. My life is like a messy desktop. There are no patterns; nothing is ever in the same place. I lost my green card, which is like a big no-no. I recently found it inside a vase.

ED: Are you serious?

JT: I’m serious. The vase wanted to be a wallet. I’m very disorganized, but I care a lot about the way things look. So it’s not a lack of interest in aesthetics, obviously. But if there are ever any compartments in my life, those boundaries are immediately broken.

ED: But you ascribe a lot of meaning to these shapes and these objects. What was it like for you growing up with stuff?

JT: Well, my mom is an architect and my dad is a civil engineer. My parents have a sense of humor where they make fun of objects a lot, because they’re so keen on what looks good and what looks bad. My parents both detest curtains, and I think I have grown to detest curtains and excess fabric. Like, privacy means nothing to them. That’s to them a very Puritan, shame-informed, tacky concern—to have curtains in your house. Also, they are very into making fun of architectural mistakes, like things that are poorly measured—little shape accidents—so I feel like my mind was trained to find humor in these things.

ED: And that relationship you had with them growing up carries through to today?

JT: When I started doing comedy I thought, My parents won’t understand it. They don’t consume comedy; they don’t consume stand-up, and that’s fine. I had no beef with that. I thought, I’m doing this thing that’s so foreign to them they won’t be able to engage with it in the way my audience will. But then my father really loved and understood My Favorite Shapes and the book and it’s like, Oh yeah, this makes perfect sense because I’m doing work that is a result of being their child. So of course they understand it. They are the seed of it.

ED: You have a design vocabulary that’s very colorful and bright, but you’ve said that your favorite color is clear. How does color inform the way you express some of these more complex ideas?

JT: I have a very emotion- and mood-oriented relationship to color. I mean, we all do, but when I first started doing comedy I was in a period of my life where I was only wearing black, white, and gray. I felt like I hadn’t earned color yet, like I didn’t have time to waste on color. It was when I was broke and solving immigration issues, so I was very monklike. Then I bleached my hair because I thought I had been dark for so long and I had been absorbing, and now I wanted to reflect. And now I’m in a very playful mood. My sister [a fashion designer] and my mom codesigned the My Favorite Shapes set, and it’s interesting that the book is so pastel and that the set was so pastel—that my sister’s and my mom’s first inclination to colors I would like are pastel. I think there’s something in the emotionality of my work that is often interpreted as pastel.

ED: It’s a wavelength.

JT: It’s a wavelength, and I think a bit of a misreading. I like it—I think the book looks beautiful and the set looks beautiful, but there is a tenderness there that is a little too literal, maybe. Right now I’m red and green and silver and a little less sweet.

ED: I’m curious if you’re a “shoes on” or “shoes off” person.

JT: Shoes off, but I don’t enforce it.

ED: So it’s meaningless.

JT: I just hate telling people what to do, or how to live their lives. So, shoes off, and they’ll see me with my shoes off, and they should maybe intuit to do the same—or they’ll actively reject it, and that to me is more important than the floors being clean.

ED: Has anyone ever actively rejected removing their shoes?

JT: No, no—but I see people definitely clocking it and then, like, conveniently ignoring it. And I’m like, if that’s where you are then that’s where you are, and that’s fine.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Sean Santiago is ELLE Decor's Deputy Editor, covering news, trends and talents in interior design, hospitality, travel, and luxury. He writes the So Courant! column for the magazine and elledecor.com.