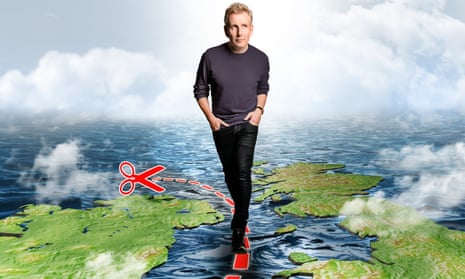

“A comedian shouldn’t be getting on stage unless they’ve got something to say,” according to Patrick Kielty – and his new set Borderline is accordingly substantial. The TV presenter and comic was moved to make this first show in six years by political developments concerning his native Northern Ireland. This “module on borders”, as he deprecatingly introduces it, recounts his youth in the country, and its journey to fragile stability – at least until Boris Johnson entered the scene.

What this could be, then, is a tirade by a man who grew up during the Troubles, and whose father was murdered by paramilitaries, against the current government’s high-handed recklessness towards the region. But Kielty isn’t that kind of comic. His father’s killing is touched but not dwelt upon. He makes clear his dismay at recent developments, but strives for a consensual – and light-hearted – way of expressing it.

We begin at his beginning, in 1970s County Down, where children are segregated by religion and raised in deep suspicion of one another. His was an unsafe childhood, says Kielty – not just because of the Troubles, but the smoking and the lack of seatbelts too. He grew up neither Irish enough for the Irish nor British enough for the Brits – “non-binary before it was a thing,” he jokes.

But Northern Ireland got past that – with the help of Mo Mowlam, whom Kielty adores, but also by reaching across divides and considering the world from others’ points of view. “None of this is easy,” he says, with reference to his own suppressed apoplexy – very funny, this – when seeing his kids in England football kits. But it’s what we need to do, Brexit-era Brits more than most, if we want to live together well.

Perhaps Kielty’s wisdom and even-handedness on these subjects, while admirable, militates against wild comedy. And I’m not sure his closing routines – on a pool party at John Legend’s house, and a get-together with his wife’s family, the Deeleys – adequately illustrate his point about widened perspectives. But this remains a thoughtful and effective show, preaching Northern Ireland’s hard-won lessons to a world that seems to have forgotten them.

At Soho theatre, London, until 2 July