Story by Sammy Ferris

Video by Jacob Karabatsos

Photos by Carmen Chamblee

Audio by Aurora Charlow

Years ago in Rockingham, N.C., Judy Harris sat at her piano while five year old Jennifer Murrary climbed up onto the bench.

As music made by novice fingers finding their way around the keys filled the room, neither one could imagine that little Jennifer would one day have children of her own who she would send to Miss Judy for lessons too.

Over the years, the Murray family and Miss Judy have been bound together by the sounds and stories of her Baldwin spinet piano. But as fewer parents sign their children up for lessons, that song may be softly fading.

Since 2020, piano lessons are down 33 percent across America. Sales of acoustic pianos have been plummeting: according to the National Association of Music Merchants, acoustic piano sales dropped 60 percent since 2004. This decline is due to a variety of reasons. Students are opting for video games or recreational sports. Music is the first program cut from schools with shrinking budgets. The idea of sitting alone at a piano rather than being with friends and family makes piano seem like a punishment.

Judy Harris has seen the drop in demand too, but she knows that the shift means more than just the loss of the ability to play piano. The role piano teachers like Harris play in their communities is that of teacher, confidant, and mentor.

When the music stops in a small town, like Rockingham, so does the community kept alive by piano teachers.

“She is creating musicians and keeping music alive in our community where it seems like music could be dying,” says Cameron McDonald, Harris’s former student.

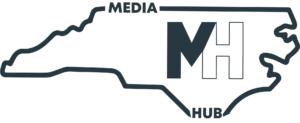

Harris has been teaching lessons since she graduated from college with a music degree from the University of North Carolina Greensboro decades ago. Her students from age four to 70. Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star and Minuet in G Major by Johann Sebstian Bach are Miss Judy classics — staples of her spinet.

She makes her living by offering affordable lessons in her town, charging a mere $12 per 30 minutes. But she doesn’t approach music like a lot of traditional teachers — she believes music should be an outlet for expression and a practice for life.

“Once you learn the mechanics of the piece, at that point, to me, that is merely replicating the symbols on the page. It becomes music at the point that you get out of your head and play from your heart. I always tell my students to ‘get out of your head, play from your heart.’ And at that point, it becomes music. Because it lives. It’s a breathing, living thing at that point,” says Harris.

Along with her private lessons, she teaches kinder music, was a Music Director at her local church, and led local handbell choirs. And while Murray’s children — Ally and Ty — are the two she calls her own, her impact extends outside of their family.

“When you’re in education you are more than just a teacher, you’re a counselor, psychologist, nurse, and mother and you wear many hats when you are in the education role,” says Harris.

Stepping into Harris’s home feels like biting into a homemade cookie fresh out of the oven: familiar, warm, and the kind of comfort that comes from withstanding the test of time. Her presence feels the same.

“She had a warm, caring, compassionate way about her. You just felt like you were at home,” says Murray.

Murray still has her first piano lesson books stashed in her house. The cover of “The Sheperd’s Reverie” is a man lying back, gazing at a crescent moon while sheep meander around him. These books are a reminder of the metaphorical home Miss Judy and her built together around the piano.

Harris’s aurora extends to all her students. In her kinder music class, the children are drawn to her.

As they sit together in the classroom, the students gather around Harris’s feet. Her presence eases and excites them, and it is as if she has an orbit around her; the students pulled in by her voice. They are currently learning the Itsy Bitsy Spider. Harris teaches with such an mesmerizing rhythm that the children jump at the end of the story, jolted by the thought of a spider falling down next to them.

She wants her students to realize the power that music has to take them to a different place — to give them an outlet for all that life throws their way.

“If you’re upset with a sibling, parent, situation, instead of saying something back you know you’ll get in trouble for, go to the piano, get a piece that represents how you feel, and play it, if necessary, multiple times. Or pick a myriad of pieces. If you’ll just give into that, when you get up, you truly will not remember why you sat down,” Harris will say to her students.

She encourages students to do this at home and during their lessons with her. In the same den as her piano is a couch where students can talk to her like a friend and mentor. She knows the importance of letting emotions into music, allowing one to influence the other.

“Many times, my students will come in after school, and the frustration or the joy or the sadness of something that has happened in school spills over into the piano lesson. There are times that I get to say here is how you can use music to cope with whatever life has handed you that day,” says Harris.

She believes in the power of music, and she takes the time to show her students its importance outside of the lessons as well.

When Murray was 7, Harris took her to her first live music show in Rockingham. She watched the performance with wonder as colorful costumes danced across the stage and dance moves kept time with the music.

“It was the first time I realized that music was the one thing that made my brain stop thinking,” Murray says.

In Rockingham, Harris believes her town does not embrace the arts as they once did — at school, home and even church.

“It is really a societal issue, and I think it stems from a lot of different perspectives. You do not see as much music for children in churches. Schools do not emphasize music education as much as they used to,” says Harris.

Long gone are the days where the piano was how to fill a home with music; phones and Alexas have taken its place. But they’ll never connect to more than just Bluetooth.

Harris’s gift of maternal love towards her students is what gives her piano its power.

“I knew the foundation she gave me is exactly what I wanted my children to have, I had strong parents that knew exactly what I needed and I knew exactly what my kids needed… a JUDY!,” says Murray.

Her close relationship with Jennifer Murray’s children began when Ally was first born. Harris says that her sister had decided to move, taking Harris’s beloved nieces with her. She was heartbroken. Three months later, her parents asked if Judy could keep Ally while they both worked.

“I would have loved nothing more than to have been a biological mom and a stay-at-home mom. That did not work out and that’s OK. I feel very blessed that I have been able to help raise my nieces and Ally and Ty,” says Harris.

Piano lessons allow Harris to be part of the lives of families and to make sure that music is too.

“Well, she’s never married, and she’s never had children. So I think it fills that nurturing nature of hers. She loves to be with children all the time. It’s her job as well. She makes her living teaching piano, doing kinder music, and being a nanny to these children,” says Brenda Tyler, her co-teacher and friend.

Harris’s dedication to her students is magnetic. McDonald, now 22 years old and a senior at Methodist University, believes that Harris taught him more than just how to communicate with music: she taught him how to communicate with people too.

“Music has helped me to be more understanding of others. I’ve always learned that music is the universal language. Music is that one mutual connection you can have with other people. It spurs relationships between people across the U.S. and in the world,” says McDonald.

He attributes his deep appreciation of piano to Harris. She provided him with a new perspective on what it means to have music in his life because she showed him that piano is more than dots on a page: it’s a language for expression. No one else in his life had been able to do that.

As music becomes less prioritized in communities across the United States, much more than a skill is lost. Harris says that during the height of the pandemic, as people craved connection and could not physically find it, they turned to music.

To her, this speaks to how important music is to everyone and an appreciation for it is not born without practice. It starts when a child is young, she believes, and the survival of music means the survival of humanity.

“Children and young people do not often find that they have outlets to express what they’re feeling, how they’re feeling, what life is throwing at them. They might not want to talk about it, and that’s fine. But there needs to be an avenue for them, and music is a beautiful one,” says Harris.

So she is doing all that she can to keep it alive in Rockingham, N.C., one piano lesson at a time.

Stories from the UNC Media Hub are written by senior students from various concentrations in the Hussman School of Journalism and Media working together to find, produce and market unique stories — all designed to capture multiple angles and perspectives from across North Carolina.

Stories from the UNC Media Hub are written by senior students from various concentrations in the Hussman School of Journalism and Media working together to find, produce and market unique stories — all designed to capture multiple angles and perspectives from across North Carolina.

Comments on Chapelboro are moderated according to our Community Guidelines