Battle of the Bilge

Published June 2022

By Brian Ted Jones | 6 min read

"Sovereign Oklahoma’s army— thirty-two boys all under twenty-one years and armed with heavy rifles—stood today Horatio-like on one end of a toll bridge spanning the Red River and defied ‘all of Texas’ to attack,” reported the El Reno Daily Tribune on July 24, 1931.

This was the height of the Red River Bridge War, a showdown between Texas and Oklahoma over a free bridge between Durant and Denison, triggered when the corporation operating a nearby toll bridge filed suit in federal court to prevent the free bridge from opening.

The two states had built the free bridge in tandem and were preparing to open it on July 1, 1931. But the toll bridge corporation had a contract obligating the Texas Highway Commission to pay the company $60,000 and an additional $10,000 over a fourteen-month period for the use of the bridge. Texas, therefore, owed the company about $200,000, or about $3.3 million adjusted for current inflation.

The court granted a temporary injunction on July 10 preventing the opening, and Texas Governor Ross S. Sterling sent three Texas Rangers to barricade their side. This sat poorly with Oklahoma Governor William H. “Alfalfa Bill” Murray, who responded on July 16 by issuing an executive order claiming the southern bank of the Red River for Oklahoma. He also sent a crew from the Oklahoma Highway Department to demolish the Texas barricades and five Oklahoma National Guard companies, including a machine gun platoon and a howitzer cannon.

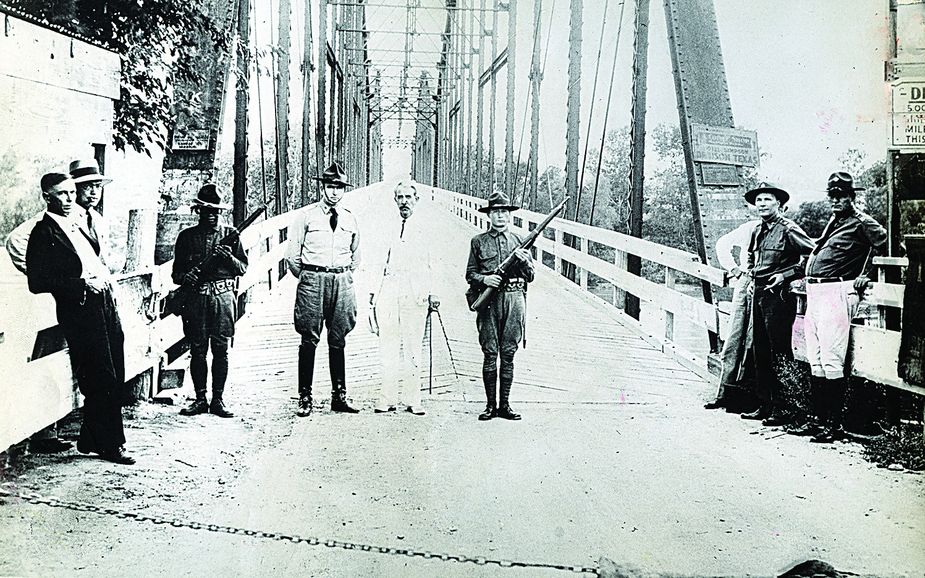

Governor Murray and the Oklahoma National Guard block traffic on the Red River bridge. Photo courtesy Oklahoma Historical Society

Sterling answered by sending more Texas Rangers to reinforce the others and to rebuild the barricades. Murray decided that if Texas could blockade the free bridge, Oklahoma would blockade the toll bridge.

Murray also declared martial law over a strip of the north bank two hundred feet wide and 1.7 miles long, “to maintain military control against all interference whatsoever,” asserting that no one, except the President of the United States himself, had authority to overrule him. By July 24, he had called up a squad of armed Oklahoma National Guardsmen and stationed them on the north bank, eyeball to eyeball with the Texas Rangers.

Murray visited “the war zone” strapped with a revolver. The commander of the Oklahoma forces, Adjutant General Charles F. Barrett, ate a ham and eggs breakfast at a hotel in Durant on the first day of martial law, spending much of the morning posing for newspaper photographers. Only the night before, an Oklahoman, possibly a sniper, had snuck across the river to taunt the Rangers.

Murray’s actions were widely praised on both sides of the river.

“His bold movement is very popular among the people of northern Texas who have direct interest in the bridges and in the traffic that flows over them,” reported Harlow’s Weekly on July 25.

Okies were even more enthusiastic.

“We trust this act of Governor Murray will not result in a war ‘between the states,’” wrote the editors of the Bristow Record. “But if it means war, then we propose to stick with Oklahoma, right or wrong.”

Almost as quickly as it flared up, though, the war died down. The Texas legislature granted the toll bridge company authority to sue the state to recover its damages under the contract, the court dissolved the injunction, and the free bridge opened for traffic.

The company did seek damages from Oklahoma, though, pursuant to Murray’s seizure of the land at the north entrance to the toll bridge. Murray treated the suit as fundamentally illegitimate, prohibiting state lawyers from responding to it under a novel legal theory involving complicated questions of federal jurisdiction, property law, and tribal rights.

His unusual strategy drew widespread criticism from both the Oklahoma legislature and the Attorney General—criticism that appeared validated when the trial court ordered Oklahoma to pay the company $168,000 in damages. After forbidding the state’s lawyers from taking part in the trial, Murray instructed them to appeal. That appeal was successful, and the damages were drastically reduced.

The bridge opened on September 7, 1931. It was demolished on December 9, 1995 to make way for a newer, safer bridge, which is open to this day.

In the end, the Red River Bridge War cost Oklahoma $1,211, and the only shots fired were from bored Texas Rangers shooting lit matches. War typically is hell, but the Red River Bridge War was heck at worst.

A portion of the original bridge is on display at Colbert City Park at the corner of Davidson Street and Timothy Drive in Colbert.