It was the Easter holidays and I was 10. We were going to see Wardour Castle in Wiltshire. My mother was driving our Morris Traveller and my eldest brother was beside her. I was giggling in the back with a cousin. Possibly my mother was arguing with my brother. He was her favourite, but growing away from her so they argued a lot. There was no radio; the car was too old for that. Both the front windows were wound down as we were in deep countryside, on a woody lane, and my mother liked fresh air.

We would say afterwards that the other car “came out of nowhere” but it simply came around a corner. It just happened to be on our side of the narrow lane, and the driver, inexperienced and unqualified slammed his foot on the accelerator instead of the brake. Their car drove ours into a bank, which made it hard to clamber out but my mother said we must all get out in case the car burst into flames. My cousin was in tears but unhurt. My jaw hurt where I had been flung against my brother’s seat. My brother’s long legs had been braced against the impact, seemingly. While he was left to deal with the weeping cousin and sheepish young driver, I led my mother down the lane to a nearby cottage so she could call the police and the AA.

The man of the house made the calls then hurried to the crash site while my mother attempted to go into social mode with his wife, but collapsed on to a chair as soon as she had a blanket over her, so I was left to drink tea and make conversation. Then an ambulance arrived and she was carried out on a stretcher. I had to go with them so I could be checked over. As we hurtled to Odstock hospital in Salisbury, with lights flashing, my mother had some sort of crisis from which the paramedic in the back with us failed to distract me.

At A&E we were separated but, as I was checked over – made to count fingers and so on – and given a painkiller for my sore jaw, I could hear my mother making strange noises from the cubicle next door, and then being wheeled away. My uncle collected me eventually and I assume our father took us home in a hire car at some point that night, although I forget the details. All I remember is that there was steak for supper and my jaw kept locking painfully when I tried to eat, so I had to slip the meat to their whippets under the table when nobody was looking.

This was 1972, so not only did our car have no rear seatbelts, the front seats had no headrests. My mother, who had a long neck, had suffered such a bad whiplash injury that she sustained damage to her brain stem. The crisis in the ambulance and the louder one I overheard at the hospital were the first in a series of strokes. She should have died, and for a month or two it was as though she had. Only days afterwards, my sister helped me pack to return to boarding school and nothing further was said on the matter.

The thinking back then seemed to be that denial and stiff routine were the best way to deal with trauma in children. Being part of two choral foundations, the little prep school I attended timetabled every minute and my days were so regulated that, even now, I can write out the weekly routine of lessons, music practice, sport and services. The outside only intruded via a daily copy of the Daily Mail and the post. After a teasing incident, my mother had been told not to write more than once a week but her eventual attempt at a letter from hospital, a scribble on the back of a lurid smiley face card she could not have chosen, baffled me for several minutes until a master explained it was from her but that “brain damage” was making her write like an infant.

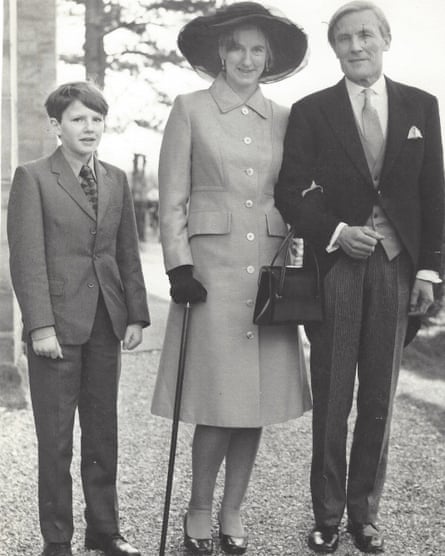

She had to learn to walk, talk and swallow again, which took months. She lost, for ever, her ability to play the piano or sing in tune. She acquired, thanks to one of those out-of-body experiences that first night in hospital, a passionate religious faith that would alienate her from my siblings who remembered in more detail the woman she had been before piety.

The experience left me with an understanding that personalities, like lives, are fragile, easily swept aside in an instant. It left me intensely self-reliant – even more than the betrayal of being parked at school had done. Some 10 years later, when we were called out of a screening of Gandhi to be rushed to that same hospital and told that my second brother, aged 25, had been killed in his car by a man who had briefly fallen asleep at the wheel after a bank holiday lunch, I was shattered, naturally, but a part of me was also braced and ready.