A year ago Emma Raducanu was focused on her A-levels. Most aspiring tennis players need to have a backup plan. A talented junior, Raducanu was not being touted as the next big thing even by those within tennis. And then came Wimbledon, breakthrough wins and an abrupt fourth-round exit that put her on the front pages, before that incredible, magical run to the US Open title.

While some parts of Raducanu’s story are wildly different from previous eras, Christine Truman finds echoes. “Watching Emma Raducanu in 2021 making her Wimbledon debut as an 18-year-old girl brought back memories of my own debut at 16 in 1957,” she writes in her new memoir, Christine Truman to Serve. Truman was – still is – the youngest British semi-finalist in the women’s singles since Lottie Dod in 1887. “Like Emma I was unseeded with no expectation, but two weeks later everyone knew my name.”

Two years later Truman reached a ranking of world No 2 and became the youngest women’s singles champion at the French Open. Her prize? A £40 voucher.

When Truman is asked whether she felt pressure walking on to Centre Court, she smiles, a little perplexed: “Pressure? I did not feel pressure. I wasn’t thinking about what pressure was. I was just thinking: ‘I’ve been practising for this, I’ve been dreaming of this. Here I am. I’m going to play on Centre Court. Wow. Terrific. This is what I’ve been waiting for.’ When I lost in the semi-final I was miserable.

“Straight after the match I was invited by Princess Marina to the royal box to celebrate. ‘What are we celebrating?’ I thought. I just lost. It didn’t occur to me that getting to the semi-final was an achievement in itself. No. I was upset because my mind was set on being the best tennis player in the world.”

This earnest, intense drive to be the best sits surprisingly comfortably alongside her father’s tendency towards understatement: “Christine enjoys a game of tennis.” Her father refused to miss a day’s work to watch her play and so missed all four of her Wimbledon semi-finals. Her mother was, says Truman, very strict. “She did not do nerves or pressure: ‘Just get on with it and don’t make a fuss!’”

Truman was the fifth of six tennis-playing children. She played mixed doubles at Wimbledon with her brother Humphrey, and her sister Nell was runner-up in the French Open doubles in 1972. Truman had to fight hard to get court time. Her first tennis lesson, at nine years old, was given to her after an older sister, Isabel, fell sick. “I was so happy,” she laughs.

In those days there was no agent and no expectation of remuneration. When a BBC producer rang their home to ask if Christine would appear in the panel game Children’s Hour, hosted by Richard Dimbleby, for £3 and 10 shillings, her mother misunderstood the offer: “Certainly not! We cannot afford that sort of money for Christine to appear on television.” For sponsorship Slazenger agreed to supply Christine with two rackets a year and Dunlop provided two pairs of Green Flash tennis shoes.

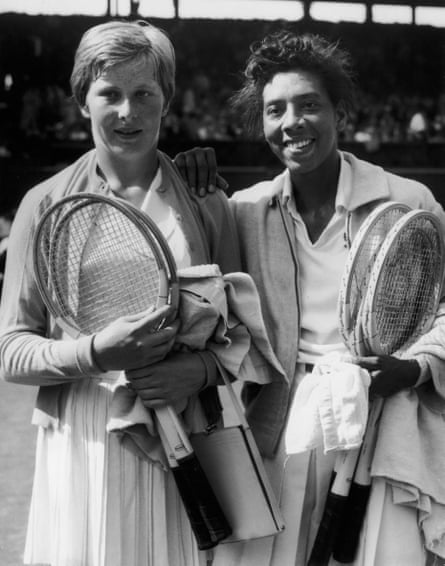

The prize for being runner-up at Wimbledon in 1961 was £15, the equivalent of just over £100 today. That money could not be spent on anything tennis related, as that would render the winner a professional. This year the runner-up will take home £1.05m and the winner £2m.Despite her amateur status, Truman trained like a professional as did her rivals such as Althea Gibson, Maria Bueno and Margaret Court. “It was not all cucumber sandwiches,” Truman says.

Truman had a physical trainer, one of the first to practise circuit training, and a one-to-one coach. But Norman Kitovitz was unpaid and – at his own behest – a secret, even from his children, until the publication of her memoir last month.

Kitovitz played to a high standard and had a private income. He watched her play in London but could not travel to her overseas matches. Still, every week for five years, between 1957 and 1961, Truman received a letter from Kitovitz. “It takes courage, patience, perseverance and the firm belief that what you are doing is right – let nobody put you off – don’t listen to a soul. You must not give up now. You have only just begun. I feel that all champions, whether in sport or other professions, have three main qualities: 1, Courage. 2, Confidence in their own ability. 3, Correct technique.”

That faith in her never wavered. “Norman was important as a coach,” Truman says. “He always wanted me to enjoy working on the practice court otherwise my improvement would be stunted … He wanted me to be instinctive, which takes hours of practice.”

She continues: “I knew what I wanted to do. I felt lucky that I was good. I was grateful for that. I was doing what I loved to do. I wanted to work hard. When I got on to court, with the knowledge that I had trained as hard as I could, I felt like I should be there. I was in the right place. I had given myself the best chance to win.”