By Martha Wessells Steger —

Special to the Eastern Shore Post —

I hadn’t given thought to marbles since my mother handed me a fistful to keep me occupied at the ages of 5 and 6 while she helped my grandmother pack strawberries at the edge of the field between Onley and Melfa. Children of the berry-pickers and I had a field day casting the tiny, shiny orbs into the Eastern Shore’s sandy loam while our parents worked.

Fast-forward several decades to other layers of meaning in rough-textured industrial marbles used by sculptor, architect, and artist Maya Lin in “Marble Chesapeake & Delaware Bay,” the most striking component of her installation, “A Study of Water,” at the Virginia Museum of Contemporary Art in Virginia Beach.

Lin has channeled 23,000 marbles into an expansive map of the bays flowing across the main gallery’s extended floorspace (interior walls removed), up the side walls and onto the ceiling. The visitor who doesn’t recognize her name would never associate the Lin revealed here with the controversial — now beloved — Vietnam Veterans Memorial, dedicated in 1985 in Washington, D.C., which brought her to international prominence when she won the public competition as a Yale undergraduate student.

As I walked around the map of marbles, light from above hit them, shifted as I moved, and hit the marbles again, creating a ripple like the pure water seen by early 17th century Europeans when they sailed across the Chesapeake Bay from Jamestown to the Eastern Shore. Industrial these marbles might be, but transparent like those I played with in the dust, they offer a fitting tribute to a bay whose watershed still sparkles despite toxic runoff channeled into it by 150 major rivers and streams and more than 100,000 smaller tributaries. The bodies of water run through six states in the watershed, which stretches from Cooperstown, N.Y., to Norfolk.

Silver, Wood, and Plaster

Just as water is commonplace for the 8 million people living within the watershed, everyday materials such as wood, plaster, and silver take on new meanings in Lin’s work. She crafted a sparkling wall piece in the exhibition — the 42-inch-long “Silver Chesapeake” — from recycled silver, which had lived another life before becoming museum-worthy art. The sculpture calls to mind two very different things: Its free-form shape resembles a piece of ginger root, Lin has said in connecting the work to her Asian heritage; but a Chesapeake Bay fisherman might see in it the silver-sided shad, a species now under threat.

The opposite of any sparkle is the 35-foot-long wood sculpture, “Flow,” depicting waves in crests and troughs with 10,000 two-by-fours cut to varying lengths, set vertically on end. The wood is a reminder of deforestation, according to Melissa Messina, guest curator of the show — the loss of forests contributing to ice melt, coastal flooding, and quickening sea level rise.

“Imaginary Iceberg,” a plaster sculpture resembling a large, unopened oyster shell, suggests rising sea level with half of the shell submerged. Despite the visual allusions, Lin hasn’t used the exhibition to point fingers; she’s focused on natural materials’ beauty and harmony in ways that open visitors up to new ways of seeing them.

“What Is Missing?”

She’s chosen as her memorial the theme of resilience, creating a website — www.whatismissing.org — which shows images and memories of disappearing species, and references conservation efforts directed at a turnaround. Residents and visitors to Hampton Roads communities can view “What Is Missing?,” jot down their thoughts about losses they’ve witnessed related to the Chesapeake Bay, and tape written examples of resilience they’ve seen onto a designated wall.

The website and wall reflections serve as a monument to the extinction of plant and animal species world- wide, though Lin has written of bodies of water as “living, unified organisms.” Alison Byrne, the museum’s deputy director, exhibitions and education, and a native of Ireland, relates to the installation as “greater appreciation of where I live and how we can do better, as individuals and as organizations working together — the way the museum worked with the Chesapeake Bay Foundation for this exhibition.”

Extinction vs. Resilience

“We are experiencing the sixth mass extinction in the planet’s history,” Lin wrote on a wall at the museum, “and the only one to be caused by the actions of a single species — mankind. On average, every 20 minutes a distinct living species of plant or animal disappears. At this rate, by some estimates, as much as 30 percent of the world’s animals and plants could be on a path to extinction in the next 100 years.”

I hear my father’s voice from decades ago, talking of runoff resulting in too much nitrogen and phosphorus endangering the bay’s population of crabs and oysters as well as the critical habitat of bay grasses. Seagrass — my piece jotted down for “What Is Missing?”

Lin has paternal memories, too — playing with marbles in her father’s studio when he was creating ceramics as well as teaching art at Ohio University in Athens, Ohio, where she grew up.

She visited the Virginia MOCA in mid-April for three days to tweak the show, attend a few private events, and deliver a lecture (which visitors can see on video at the museum). “The Chesapeake Bay — which is why I’m so excited to be here,” she said, “has played a very large part” in her museum sculptures. “From an ecological point of view, it is one of the most critically important bodies of water in this country.”

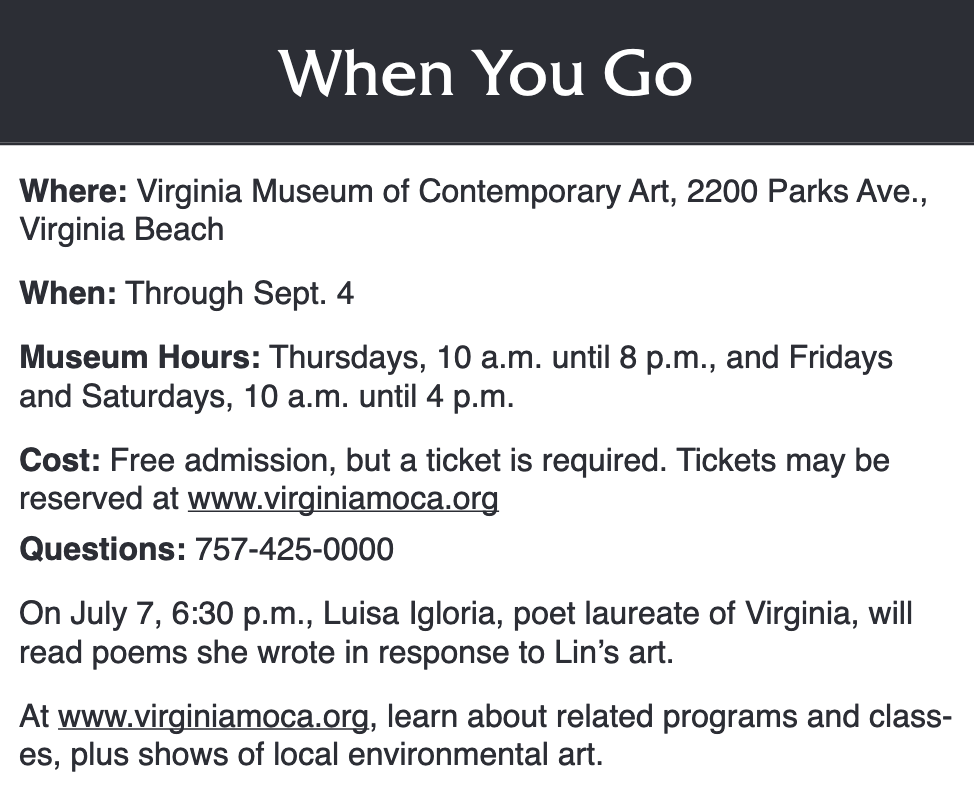

Update: Virginia MOCA is also open on Sundays, 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Free admission and tickets are encouraged but not required for all days. Tickets may be reserved at www.virginiamoca.org.