Colton Haynes first came to fame as an all-American dreamboat on Teen Wolf, MTV’s breakout scripted hit from 2011. His character had a girlfriend, and he was assumed to be hetero offscreen. But soon after his acting debut, queer publications unearthed surprising pictures of the onetime Abercrombie and Fitch model posing for the queer youth magazine XY.

On the magazine's cover, Haynes, then 17, gazes at the camera while embracing his real-life boyfriend. The juxtaposition of his generic MTV teen dream image and the newly surfaced imagery of queer love was especially striking back in the 2010s, before a generation of young out stars defined a new Hollywood era.

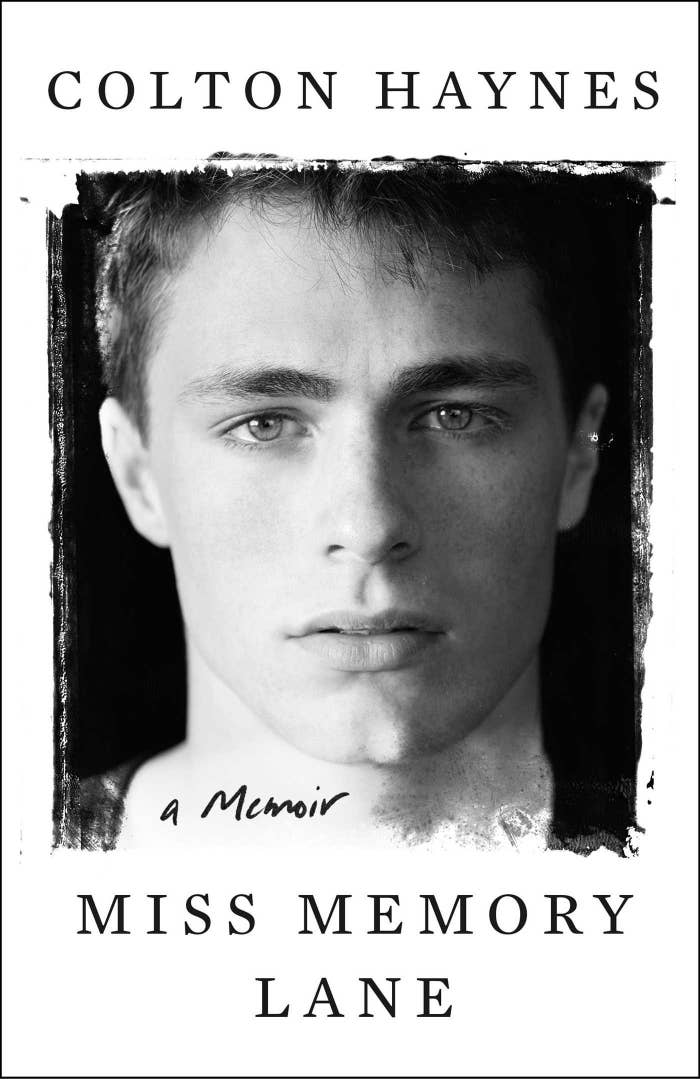

As Haynes became more and more famous — he later played a superhero sidekick on the CW’s Arrow — he was out to neither the public nor the industry. “I was always fixing my hair, checking my reflection,” he writes in his new memoir Miss Memory Lane, “swerving any indication that there was something feminine or gay about me.”

He finally came out on Tumblr in 2016, and the 33-year-old has since become one of the more candid young gay celebrities, sharing his struggles with addiction, marriage, and divorce.

Miss Memory Lane is a vulnerable meditation on gender, desire, and fame, and what it felt like living up to his straight public persona. At a time when Hollywood pays lip service to inclusion, even while casting straight men in queer roles, and sanitizing queer men’s lives for straight audiences, his grappling with the industry’s anti-femme attitudes is especially relevant.

Haynes grew up precariously working class in small-town New Mexico and Kansas. His parents’ lusty yet toxic relationship kept him and his siblings in a constant state of emotional and geographic flux, until his father left.

He mostly lived with his mother, a sometime bartender who struggled with addiction and making ends meet. She often turned to men for help. “They revolved in and out, never staying long,” he writes. “They were uniformly ugly, and they paid some of my mom’s bills, which she had a bad habit of tearing up, unopened.”

He writes, too, of being sexually abused as a child by his uncle, which taught him that his worth was intertwined with his appearance. “Doing things like that — sex things — was going to give me that sensation again, the feeling of being desired, the feeling of getting someone else’s attention,” he writes.

That belief played out in his evolving relationships with his body and the men in his life. From being groomed by a 42-year-old cop when he was 14 to finding his first real relationship with the boyfriend from the XY magazine spread, he chronicles the struggle to see others for who they are and to be seen himself. “I wanted people to be consumed by thoughts of me,” he confesses, “but most of the time I didn’t actually want to be touched.”

These attempts to understand himself were also distorted by his entertainment industry ambitions. He got his foot in the door thanks to his look — corn-fed Kansas jock — which led to photographs by the king of mainstream homoeroticism, Bruce Weber.

The wholesome-looking masc gay who passes as straight for Hollywood is now a long-standing trope, from the clean-cut blonde charm of Tab Hunter to the more debonair sophistication of Rock Hudson. In some ways, Hollywood is supposedly more open to queer stars now than ever before. The current crop of queer rom-coms like Fire Island and Bros speak to a new generation of creators who can lean into slightly less straight-gazey representation.

Yet Haynes’ writing on what he experienced coming into acting just a decade ago is sobering. In one essay excerpt that was widely shared last year, he writes about working with one manager who expected him to get rid of his “theater” mannerisms and “overly” animated way of talking.

All of this undermined the effects of his prior experiences exploring his identity unconstrained by appealing to mass audiences. Haynes writes about performing in his mother’s heels, feeling bonded to her because of it, and finding himself in theater classes and queer clubs. But the virulently anti-femme attitudes he encountered in the industry slowly seeped into him. He notes how, by the time he was cast on Teen Wolf, “My demeanor was chipper, but my voice was low, and my mannerisms were on mute.”

Wearing flannel and letterman jackets to auditions informed “that varsity style to help butch [himself] up a bit.” He added, “But I had learned the tools I needed to suppress my affect, to make my personality match the way I looked — like a stupid, dumb jock — with just enough silly charm that people would still like me.”

Despite all his success, he felt lonely and yearned for the freedom he’d once felt. Even as he scored endorsements and increased his social media following, his managers, industry colleagues, and the producers of the shows he was working on urged him not to come out. When the XY pictures resurfaced, he and his team sought to scrub them off the internet.

Some of Haynes’ industry tales will probably spark celebrity guessing games: He alludes to a producer who was not out and whose nerves were shot when he “got fucked too hard by a guy with a truly massive dick,” and a famous gay screenwriter who told Haynes not to come out.

Yet he also delves into more intimate moments, examining the detrimental relationship patterns he inherited from his parents, struggling to find endorsements after coming out, and the ebbs and flows of falling into addiction. He writes about signing a nondisclosure agreement that seemingly prevented him from talking much about a monthslong marriage (Haynes doesn’t name the former spouse, although he filed for divorce from celebrity florist Jeff Leatham in 2018), after which he hit rock bottom.

But he’s candid about getting there. “I was drunk and reading comments from gay men on the Internet,” he writes, “people I had never met, calling me a fat washed-up divorced flop, perpetuating the lie about how I was the only gay who worked in Hollywood, even though I was barely able to get one job after coming out.”

We’re in something of a golden age for celebrity memoirs written by women, as a generation of actors and pop stars reclaim the images that made them famous but also often were created without their input. The same can be said for memoirs by queer and nonbinary celebrities, from Billy Porter’s Unprotected to Jonathan Van Ness’s Over the Top, which make sense of queer trauma but also attend to the joy.

Haynes similarly reflects on his shifting relationships with his gender and queerness in a compelling and nuanced way. He seems self-aware about how his appearance opened doors and his fears about aging in the industry; by the book’s end, one senses he’ll have the resilience to stick around.

Toward the closing chapter, Haynes captures a touching moment with a friend who interrupts him as he’s sifting through letters, photographs, and memories after his mother’s death. “Whoa,” he says. “Miss Memory Lane, huh?” It’s a fitting title for a sensitive self-portrait, woven from fragments of his past. ●