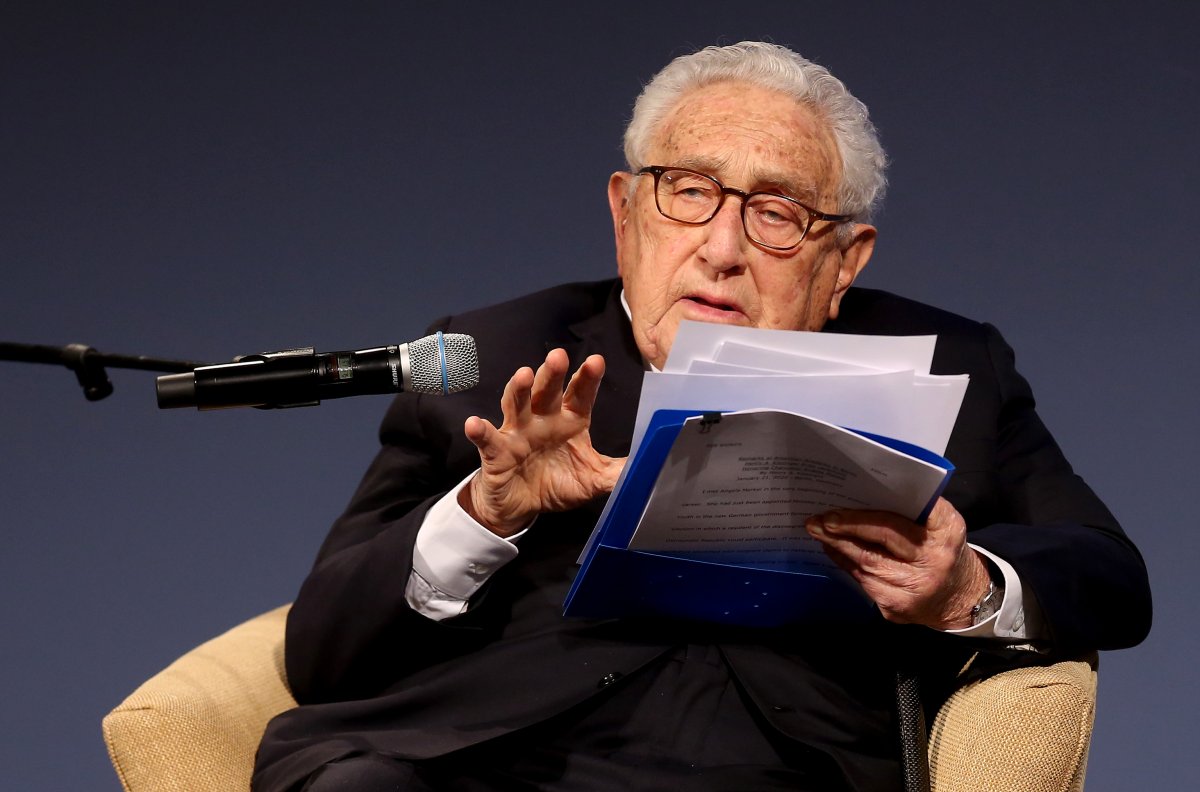

Henry Kissinger is one of the most controversial public figures in the modern era. The former U.S. national security adviser and secretary of State evokes a range of strong emotions. Depending on who you ask, Kissinger is either the quintessential realist who orchestrated the split between Communist China and the Soviet Union or a war criminal who approved over 3,800 bombing raids in Cambodia.

Kissinger, who turns 99 years old on May 27, has generated even more controversy for himself. Speaking at the Davos World Economic Forum this week, the former statesman had a piece of advice for the Ukrainian government: it's time to think about a diplomatic settlement to end the war, and that settlement will have to include territorial concessions to Russia. "Ideally, the dividing line should be a return to the status quo ante," Kissinger surmised, referring to the pre-war lines in which Russia controlled the Crimean Peninsula and approximately a third of territory in the Donbas. "Pursuing the war beyond that point would not be about the freedom of Ukraine, but a new war against Russia itself."

Kissinger's suggestion was met with pushback almost immediately. Hours after Kissinger spoke, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky reiterated his government's position: there will be no peace talks until Moscow withdraws from every inch of Ukrainian territory, including Crimea. Steven Pifer, a former U.S. ambassador to Ukraine, tweeted that "Ukraine's territory is not Kissinger's to give Russia." Edgars Rinkevics, Latvia's foreign minister, went as far as to compare Kissinger to Neville Chamberlain, the British prime minister who will forever be remembered as the man who ceded the Sudetenland to Nazi Germany in 1938.

It's easy to understand why Kissinger's remarks produced such scorn. For one, Ukraine is the victim in this entire affair. Russia's invasion is the very definition of a war of aggression, and the Russian military has prosecuted it in the most heinous way imaginable. War crimes have been committed at the hands of Russian soldiers. Entire cities have either been damaged, or like the coastal metropolis of Mariupol, wiped out. Conceding anything to the aggressor leaves a sour taste in our mouths; one can only imagine how bad the taste would be to those who have lost loved ones.

Second, the Ukrainian government and people believe conceding territory to the Russians is dangerous. Mykhaylo Podolyak, Zelensky's chief negotiator with Russia, reiterated Kyiv's position that granting territory to Russia in exchange for a ceasefire or a peace agreement would simply wet Russian President Vladimir Putin's appetite for more land. According to a recent survey conducted by the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology, 82 percent of Ukrainians don't support territorial concessions in a hypothetical peace accord.

There is also a feeling of extreme confidence within the Ukrainian government that Russian forces can be defeated on the battlefield. Kyiv's negotiating position has hardened as the war has gone on, fueled in large part by the successes of the Ukrainian defenders and the bumbling of the Russian invaders, who continue to be hamstrung by the same morale issues, logistical problems and difficulties with command that have plagued the campaign since its inception. The notion of Ukraine routing a much larger and better-armed Russian military, something dismissed as a fantasy in the early days of the conflict, isn't so crazy anymore. Some commentators in the West are advising the Ukrainians to fight until Putin, and by extension, Russia, is humiliated.

War, however, is an unpredictable beast. Those who have the battlefield momentum one day can lose it the next. Combatants learn from their mistakes and adapt to setbacks. The Russian military is no exception. After a multitude of losses and tactical retreats, the Kremlin realized that attacking Ukraine across multiple axes was a stupendously idiotic idea that exhausted the Russian military's supply lines, underestimated the Ukrainian military's warfighting skill and spread Russian units across too many fronts. The Russians have changed their war plan from capturing the entire country to expanding their hold over a specific part of Ukraine's territory—the east and south. The shift in objectives is having an effect; Russian forces have blocked Ukraine's access to the Azov coast and created a land-bridge between Russia and Crimea. While Moscow's attrition rate is no doubt high, Russian forces are making gains on the ground, particularly in Luhansk. Severodonetsk is now at risk of being surrounded. The Ukrainian army certainly possesses the will to fight these advances for as long as the war proceeds, but will it continue to boast the capability?

The Ukrainians also have to contend with the possibility of war fatigue hitting the West. To date, the U.S. and NATO have been solidly united in support of Kyiv, providing the Ukrainian army with ever more sophisticated weapons systems like M777 howitzers. But as the war progresses and the casualties pile up, there may come a time when the West becomes increasingly divided over Ukraine policy and what the end-game should look like. While the U.S., the U.K., Poland and the Baltic states want to deal Russia a strategic defeat, Germany, Italy and France are more concerned with ending the war at the earliest possible date. Zelensky may scoff at the notion of a ceasefire, but as the fighting persists, he can't ignore a scenario whereby some Western leaders who are now committed supporters of Ukraine's position begin to re-evaluate their policy.

Nobody, including Henry Kissinger, should be telling Ukraine what to do. Ukrainian policymakers will have to make their own decisions as to whether a negotiated resolution is the best way to save their country—and, if so, what terms are acceptable. Right now, the answer appears to be "no." But over time, the pendulum could swing to "yes."

Daniel R. DePetris is a fellow at Defense Priorities and a foreign affairs columnist at Newsweek.

The views expressed in this article are the writer's own.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.